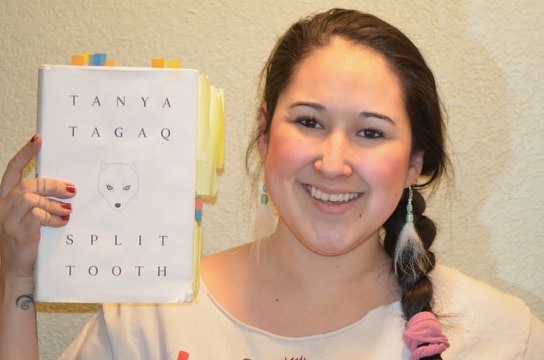

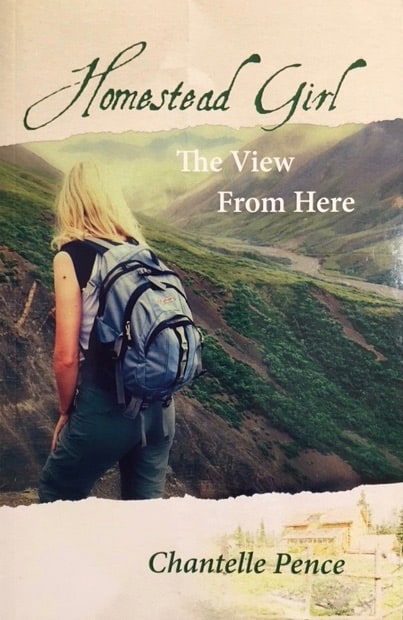

On a bright winter day last February in a room above the University of Alaska Bookstore in Anchorage, author Chantelle Pence talked to her audience about her first book, Homestead Girl: The View From Here, © 2016, Copper River Press. She, and several Athabascan speakers, discussed growing up in rural Alaska. They spoke from various perspectives. They spoke with heart. And they reached our hearts.

Compassion at the Edges

Compassion at the Edges

Afterward, my children’s father, a traditional hunter and trapper from an interior rural Alaskan village, was reflecting about the speakers, and the book. We were rushing around Anchorage, heading to school to pick up our children. I glanced at him as I was driving, and saw tears falling down his face. He was as surprised as I was by his reaction to the speakers and book reading. We both read the book that week. And I re-read the book again early one morning in late December of 2017.

Chantelle’s collection of essays starts with stories about those who came before (The Ancestors), describes the people who live there now, (The People), and wraps up with vignettes about life in the region she calls home (The Place). She shares pearls of wisdom she learned by growing up Nondlae, white, on traditional Ahtna Athabascan lands in rural Alaska. As a snapshot in time of the late 20th and early 21st century, she paints a view that reflects the multi-faceted edges of many transitions: between being white and Alaska Native, between traditional and modern ways of knowing, and of survival, between urban and rural Alaska.

On dealing with conflict, she captures the nuances of handling tension in small communities, realizing that “To ignore is better than to instigate,” (p. 77). By avoiding interaction when emotions are still heated, damage can be avoided, allowing healing to work over time for the next time you see the person in question. This is a lesson that is taught early on for those from small rural villages, but is learned anew by ‘outsiders’ coming in from more urban or western cultures.

A Sense of Place

She describes knowledge born of place, in an obituary of ‘the steward of the Upper Copper River traditional fishery,’ and later, of her own parents, who trapped for a living and understood the rhythms of the population changes of the animals. “Those who live close to the land are true biologists. They don’t always have a degree to prove their mastery, but they know the track of each animal and their patterns. They do not read it from a book; they read it on the ground. They understand how many can be harvested in any given place, not just because of a rule or regulation. They live with the wildlife and know the population.” (p. 125)

Survival at the Intersection

At the intersection of culture and survival, she is humble about the individual approach of the western world from which she originated, and the traditional values of the community in which she grew up. In the chapter ‘Salmon,’ she admits to irritation with being called up on the phone and asked to share the last of her salmon, and describes the emotional and spiritual transition as she moves through these feelings to a place of gratitude and love, expressing appreciation for the salmon and the Ahtna for their lessons. In a line of sheer poetry, she writes, “I was called to the altar by a woman on the line, where I was baptized by glacier water and salmon slime. It set me right.” (p. 111)

In rural Alaska today, traditional subsistence culture faces a multitude of challenges, including environmental changes in the land and wildlife, increasing regulations around subsistence activities, out-migration from the villages of families with young hunters when rural Alaskan schools dwindle and sometimes close, and the more subtle but no less significant pressures of cultural ambivalence for youth growing up from more than one culture and struggling to navigate their ‘place’ in the world. Chantelle brings language to many of the largely felt, rarely verbalized, internal struggles that many Alaskans live with day to day in these times, as so many are quietly surviving at these intersections, navigating new terrain. By sharing freely of her own struggles, and extending deep compassion, she connects with her readers and provides us all an opportunity to become more compassionate with each other. I look forward to reading more from this writer.