Village School Libraries

When I first moved to a small village in rural Alaska, I would go hang out in the school library. A lot. It was the public internet access point, and as such, a gathering place for the village. I was amazed to find so many books there, in this tiny community off the road system where the cost of shipping goods exceeded $1/pound. Old books. New books. Lots of stories by writers I knew. Lots of history about Alaska, by writers I’d never heard of. But in that library, I struggled to find books by indigenous women authors.

A few books were by Alaska Native men (Sidney and James Huntington come to mind), but very few by Alaska Native women. And nothing by Louise Erdrich, who even then was a renown American Indian writer. Having read Love Medicine during my years in Minnesota, I wondered at this absence. Didn’t the children of this village need to see themselves reflected? To understand their own history as indigenous people in this country, through the lens of the books they were expected to read in this public school which they were required to attend, often in conflict with their families’ traditional subsistence activities?

A few books were by Alaska Native men (Sidney and James Huntington come to mind), but very few by Alaska Native women. And nothing by Louise Erdrich, who even then was a renown American Indian writer. Having read Love Medicine during my years in Minnesota, I wondered at this absence. Didn’t the children of this village need to see themselves reflected? To understand their own history as indigenous people in this country, through the lens of the books they were expected to read in this public school which they were required to attend, often in conflict with their families’ traditional subsistence activities?

Looking for Indigenous Women Authors

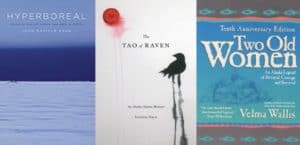

As the years went by, and I watched the village children grow up, I also observed the teachers who would pass through. Some were Alaska Native, some weren’t. Some would stay less than a year and leave in a bluster of frustration when the dark and cold and unreliable plumbing of the north proved too much for their temperament. Some would appreciate the richness of culture and moose meat and salmon, and stay for three years, leave, and come back for more. Some brought the kids Raising Ourselves, and Two Old Women by Velma Wallis. None put copies of Love Medicine, nor Beet Queen, nor even Birchbark House, by Louise Erdich in the library for the kids or adults. I’m thinking now, I should have just done it myself. I know, I should have. Maybe starting this publishing company  is my way of making up for that. Because I also want my own children to see their roots reflected in the stories they read. And yes, I want them to read—as both their father and I read—voraciously. While I realized that there aren’t a lot of female Native Alaskan authors with published stories, I wanted the library to reflect stories of what it is like to grow up on the land, with families stretching back through generations of pain and love and confusion and richness of spirit and tradition and language and food. Stories of struggles to maintain culture and traditions in the face of modern day changes, such as Linda Hogan’s Pulitzer

is my way of making up for that. Because I also want my own children to see their roots reflected in the stories they read. And yes, I want them to read—as both their father and I read—voraciously. While I realized that there aren’t a lot of female Native Alaskan authors with published stories, I wanted the library to reflect stories of what it is like to grow up on the land, with families stretching back through generations of pain and love and confusion and richness of spirit and tradition and language and food. Stories of struggles to maintain culture and traditions in the face of modern day changes, such as Linda Hogan’s Pulitzer  Finalist Mean Spirit, about the oil boom’s impact on American Indians in Oklahoma, and Solar Storms, about a girl coming of age in the foster system and then returning to her ancestral home near the Minnesota-Canadian border and contending with development plans for a hydroelectric dam. Such stories exist, and these stories from other indigenous North American writers, both male and female, carve the way for more stories from Alaska Native women writers. Because their time is coming—has come.

Finalist Mean Spirit, about the oil boom’s impact on American Indians in Oklahoma, and Solar Storms, about a girl coming of age in the foster system and then returning to her ancestral home near the Minnesota-Canadian border and contending with development plans for a hydroelectric dam. Such stories exist, and these stories from other indigenous North American writers, both male and female, carve the way for more stories from Alaska Native women writers. Because their time is coming—has come.

Representation Matters

Sometimes when I was out at the cabin with the kids and their dad, at fish camp on a rainy day, we’d get bored and read a book or magazine that was laying around. I stumbled across a Sherman Alexie book that way. Not sure where it came from, but there it was. Throughout that book of short stories, I kept seeing the word ‘enit,’ and asked their dad if he knew what it meant. He just laughed. He’d been using that term in everyday language for years, and I’d never really noticed it, recognized it. Now I hear it all the time, this contraction of the slang contraction “ain’t.” It seems like such a small thing, that one expression, one word, in everyday language, that Native American cultures thousands of miles apart, could share. But seeing it reflected in a story helped me to actually hear it for the first time. It made the word feel real. And if that’s the impact of reflecting one small detail of language on me, an outsider, I can only imagine the power of reading words that reflect your own real life, the visual details of what it means to be indigenous in America, in printed words on a page.

When Sherman Alexie’s book, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian came out, I was thrilled. Here, finally, was a book that at least reflected (a little) of what it meant to be indigenous in America. Well, maybe. Sort of. Not really like small village Alaska, not about living on the land, but some of the struggles of colonization, of internalized oppression and the craziness that begets, the anger that people take out on each other and later regret. That was in there. And, I was delighted when I learned that an entire box of those books had been shipped to the village. Yet my own children have found it depressing, did not want to read it, had a hard time relating to it. Not all books by Native Americans are created equal and that is why we need a diverse chorus of authors to reflect the variety of experiences of what it means to be indigenous in America.

#MeToo

Enter the #MeToo movement. Sexual harassment and sexual assault are pervasive issues throughout the world and major media moguls and politicians are falling right and left. Women have had enough. Behind the #MeToo movement is a groundswell of growing public awareness about the pervasiveness of sexual harassment, abuse, and assault in this country, and a refusal to be silenced. And in recent weeks, Sherman Alexie has come under the spotlight, and this has met with mixed emotions within the Native community. It’s a complicated issue. And, to be clear, this shakeup is affecting the entire children’s book industry right now, with conversations happening, awareness developing, and apologies of various degrees coming forward from Alexie and other individuals who are (hopefully) beginning to understand the impact their actions have had.

It’s about Jurisdiction

I’m embarrassed to admit I had not heard of The Round House until Louise Erdrich came to Anchorage in the fall of 2017 and spoke at UAA. It was a National Book Award winner in 2012 and has received international acclaim. As a presenter, she warmed easily to her audience, and kept us laughing initially by first reading the entire story of Le Mooz, which most of us in the audience could relate to as Alaskans, because she was talking about moose and sex and the way old couples can both love and hate each other all at once. After capturing our attention and sense of humor, she brought up The Round House. Because we had been able to laugh first, we were ready to listen. Some in the audience knew the book, and I could tell it was important by the mix of tears and cheers as she held it up.

In The Round House, Erdrich tackles the specific complexities of legal jurisdiction issues complicating justice in a sexual assault case. Thirteen-year-old Joe is just at that age of developing awareness of appropriate behaviors and boundaries between men and women, when his mother is brutally assaulted. In the aftermath, she withdraws emotionally from him and his father. The assault against his mom is an overt concrete event that divides his life in half, before and after. The event casts a shadow at every step afterward as he continues to learn important nuances of respect for women and how that is linked to self-respect in his own interactions. He is at times humbled and shamed by his own conflicting desires and motivations. Erdrich handles his development with the sensitivity of a mother, recognizing that these boys have “that simultaneous feeling of wanting to break away and wanting to protect them (their mothers) . . . They haven’t exactly thought it out, but they know exactly what’s right.” As the parent of a young teen son, I was moved to both laughter and tears as I read this book and it has deepened my appreciation for watching my own son mature.

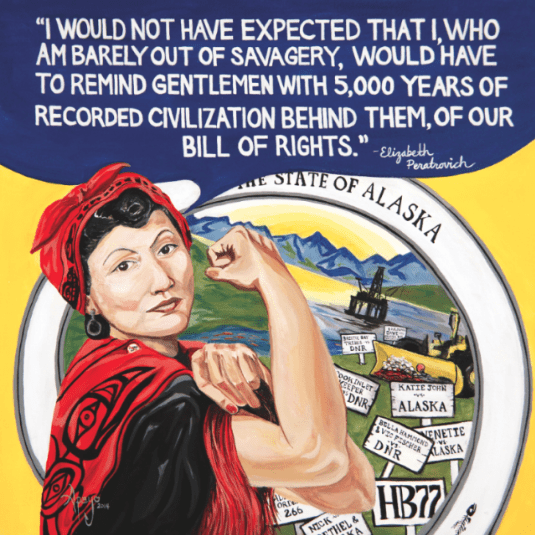

To be a woman in America today, means different levels of vulnerability depending on your ethnicity and location. In Erdrich’s words, this book is “about jurisdiction” and the horrifying legal quagmires that prevent justice when sexual assault by a non-Native male occurs on tribal lands. “Right now,” she said in an interview, “tribal governments can’t prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes on their land.” In a key scene late in the novel, she illustrates the complexities using a metaphor of a precarious sculpture of knives and kitchen implements. “That’s Indian Law,” Joe’s father tells him. “We are trying to build a solid base here for our sovereignty . . .” Although the particular legal details are somewhat different in Alaska, the lack of law enforcement in remote villages and the grim statistics of violence, still shadow the night. Alaska Native women “suffer the highest rate of rape in the nation.” If you are Alaska Native and female, life after dark is a war zone throughout much of the state, and regardless of who the perpetrator is, or where the crime is committed, justice is difficult to obtain. It’s a dark and painful topic for many.

For more history of the legal issues that motivated Erdrich to write this book, see Amnesty International’s report, Maze of Injustice: The failure to protect indigenous women from sexual violence in the USA. For more information about jurisdiction in this state, see Advancing Tribal Court Criminal Jurisdiction in Alaska by Ryan Fortson, published in The Alaska Law Review in 2015, Volume 32:1. To read about the first tribal court case, in Arizona, to attempt to convict a non-Indian under the Violence Against Women Act, see this press release from May 2017.

Diverse Voices

It’s important to realize that while Sherman Alexie and Louise Erdich are the most famous American Indian authors writing today, they aren’t the only indigenous authors. For rural Alaskans, especially our children, it’s critically important to provide a rich library that reflects the truth of their experiences meaningfully. And right now, that means “It’s time to read more books by Native Women,” as the title of Tracy Rector’s recent article in High Country News, states. “Representation matters. Positive role models can shed light on potential paths to take in life and provide windows of hope . . . Hope matters so much for those of us who carry deeply embedded historic trauma and grief. This is why . . . the allegations have been so devastating.” Rector challenges us to live with some ambiguity and the messiness of life in recognizing the need to both come forward out of silence and to acknowledge mistakes, to appreciate Sherman’s contribution to literature while bringing forward and honoring the courage of those indigenous women authors who have come forward to speak their truth about experiences they had with him. “Let’s use this very disturbing moment to challenge the literary world . . . to educate the broader public about the many talented and diverse Indigenous writers that exist,” she writes. She provides some great options for doing so, listing links

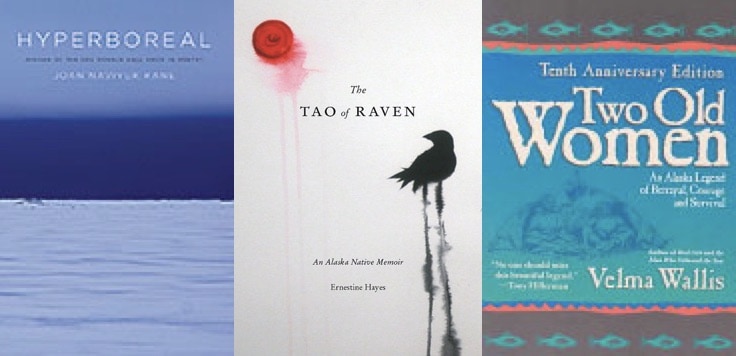

Books by Alaska Native Women: Joan Naviyuk Kane, Ernestine Hayes, and Velma Wallis.

to eight indigenous women authors featured on the article’s cover picture, as well as a link to a CBC list of 108 Indigenous Canadian authors, and this lengthy Twitter feed list by Elissa Washuta of Native writers. There are a handful of Alaska Native women authors at work as well. Check out Joan Naviyuk Kane, Ernestine Hayes, Loretta Outwater Cox, Velma Wallis. Many more indigenous women authors in Canada can be found by reviewing the link above, or checking out various lists at 49th Shelf, an online Canadian book community.

(Update fall 2018) After writing this article, more books by indigenous women women authors of the north came to my

(Update fall 2018) After writing this article, more books by indigenous women women authors of the north came to my attention. The Winter Walk by Loretta Outwater Cox addresses a somber theme, yet it also stands out for its mouth-watering descriptions of indigenous food harvesting. I’m looking forward to reading her second book, The Storytellers’ Club, later this winter. If you would like to recommend an Alaska Native or indigenous Canadian book for review on this site, please let me know.

attention. The Winter Walk by Loretta Outwater Cox addresses a somber theme, yet it also stands out for its mouth-watering descriptions of indigenous food harvesting. I’m looking forward to reading her second book, The Storytellers’ Club, later this winter. If you would like to recommend an Alaska Native or indigenous Canadian book for review on this site, please let me know.

For Our Youth

Let’s remember the very real courage it takes to be an Alaska Native or American Indian female in the world today. Let’s listen to, and believe them, and support our youth, both female and male, when they tell us something feels wrong or unsafe. While we are at it, let’s also remember the courage it takes to be a young Alaska Native male today, to grow up with tender heart and compassion and respect for mothers and friends and girlfriends, as well as courage, to hold their peers accountable for treating women with respect. Because that’s what this generation is growing up to do.

See our resources page (Freedom and Security) for links to Alaska agencies working from many angles toward improving awareness and safety for Alaskan women. (Recently published and added to the resource list fall 2018 is an article about online internet safety).

Louise Erdrich

Author, Owner of Birchbark Books

Louise Erdrich is one of North America’s most well-known Native American authors. She owns a small independent bookstore, Birchbark Books, in Minnesota which nourishes both her neighborhood and the worldwide community of literate indigenous people. For this article, I linked the books listed to her online store.

Tracy Rector

Co-founder and Executive Director of Longhouse Media

Tracy Rector’s article mentioned above was originally published as “Her + her + her: Female Native authors for your reading list by Crosscut. She is of Choctaw/Seminole heritage and is an indigenous media activist with abundant accolades for her work. You can read more about her here.

Denali Sunrise Publications Bookstore:

Please buy books at your local independent bookstore! If you prefer to purchase one of these books online, however, clicking on the ‘buy books’ button below will take you to the Denali Sunrise Publications bookstore, which sells quality books about rural Alaska online at a 5% discount off retail, including many of the titles featured here..

For coupon codes offering greater book discounts, please subscribe to our newsletter.

Thank you Lisa for furthering the exposure Native American females have had, and are still experiencing , as victims of horrific sexual abuse. The issue is slowly emerging to the conscious level of children and adults. We must not let it be covered up nor buried again….Native American girls are gaining knowledge and understanding in exposing sexual abuse….and gaining personal power to have the strength to call out for the help they need.