Cranberries in Springtime: A Literary Meeting Place for Rural Alaskans

Lingonberries, Vaccinium vitis-adaea, kwntsan’.

About this Blog

Spring Breakup in Bush Alaska

When I first moved to Alaska in March of 2000, I lived in a wall tent while building a cabin at the edge of a remote lake in the Interior. I remember eating the last apple from its box by early April, and having no fresh fruit for a month. And no bath, either, until the ice melted. In May, we started up the Honda 40 horse outboard, and rode in the boat an hour downstream to the edge of where the ice was still breaking up along the Kuskokwim River. We stopped and got out to look around, and discovered lowbush cranberries on the tundra. The flavor of this unexpected gift brought tears. After a month of eating dried fruit, porcupine, and squirrel meat, those winter-sweetened cranberries were the best thing I had ever tasted.

Living in Village Alaska

Years later, living in a small Athabascan community far upriver from where I found the lowbush cranberries, I heard stories, in both English and Athabascan, about the critical importance of those berries to survival of individuals and people of the north. My experience that day led to a deepened understanding and appreciation of the skill and perseverance of local people. And the experience connected me viscerally to the land that sustains us, in a way no words can ever quite describe. Over the years, this memory has become a metaphor, or story, that continues to instruct me in my life.

Cranberries in Springtime

Unexpected second chances in life. Sweetness rendered in this sour fruit, by winter’s bitter cold. Beauty and destruction after a forest fire; morels, fireweed, and renewed forest growth follow. Wildflowers growing up out of an old tire in the woods. Children laughing and playing. Juxtapositions. Oxymorons. Silver linings. Lemonade. Gifts of grace.

Come. Let us sit down in the moss, lichen, and berries of the tundra and know this earth that is our home. The dialectic of healing requires some messiness and discomfort, to enjoy the beauty. It is a journey I would prefer to take together.

Most Recent Posts

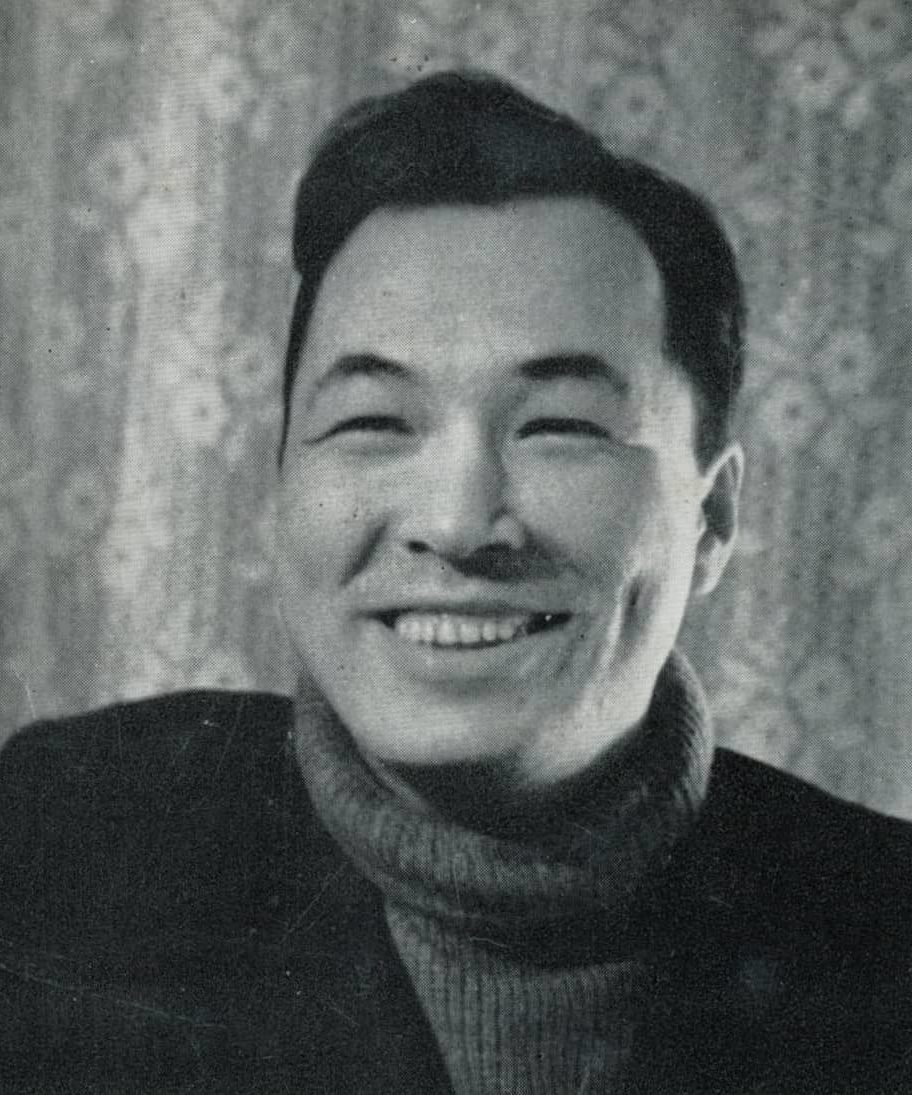

Yuri Rytkheu: Review of When the Whales Leave and other Chukchi stories of the far North

When the Whales Leave is a stunning, elegiacal creation story from one of Russia’s foremost Indigenous authors. Written by Yuri Rytkheu in 1975, this short, novella-length fable connects Indigenous cultures across Alaska and the circumpolar North with its attention to details of history and ecology. The book includes an introduction by Gretel Erhlich, and historical notes from translator Ilona Chavasse.

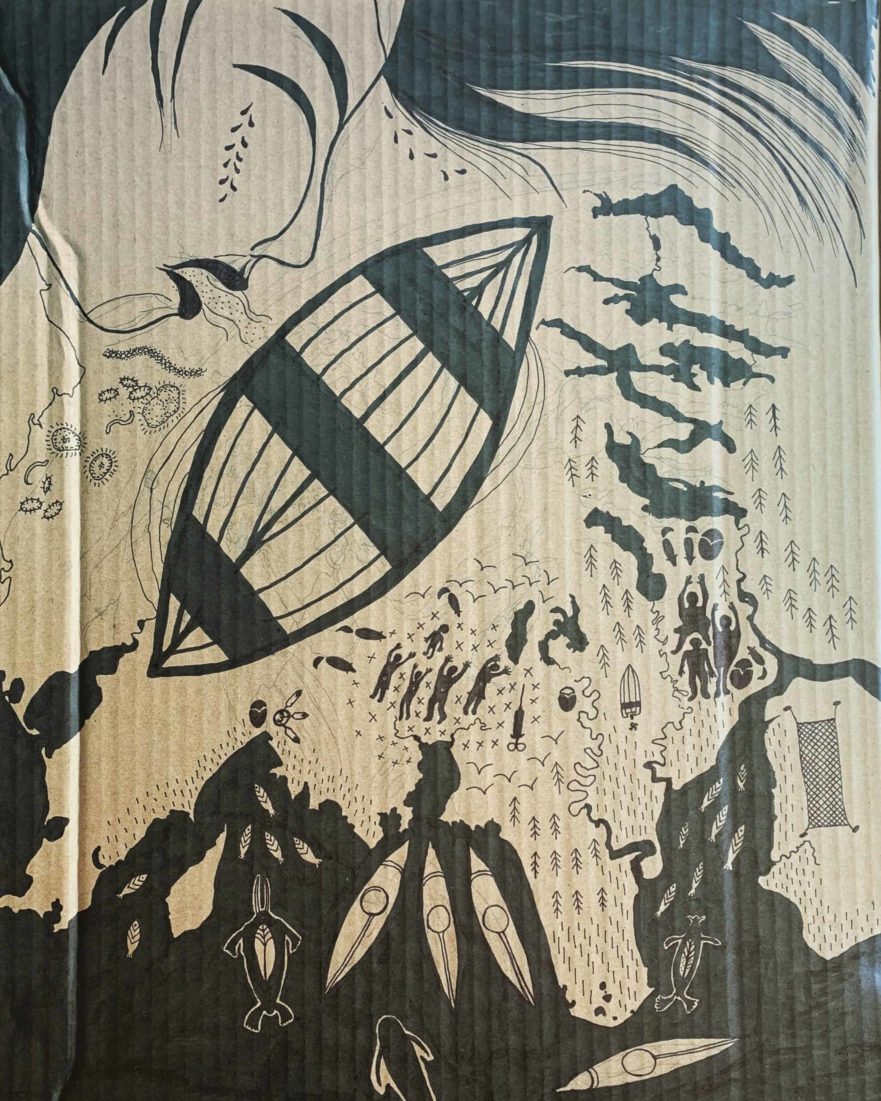

“We are resilient people”: Artist Amber Webb on surviving pandemics in rural Alaska

Artist Amber Webb describes her work above as “Sketching the story of how the Spanish Flu pandemic hit Bristol Bay in 1919 and changed the region. The map is about Goodnews Bay to the edge of Nushagak Bay. It also includes the lakes. Not a very accurate map, but it’s symbolic. They say that people from Kulukak relocated to Kanakanak, Togiak, Manokotak and Aleknagik because so many people died. I know one of my great-grandmothers was from Kulukak, but moved to Kanakanak. I don’t know if it was during this pandemic. We are resilient people.”

Under Nushagak Bluff and the shadow of pandemic in Alaska literature: Review of Mia C. Heavener’s debut novel

Seagulls swoop and dive, crying in the salty air. The waves of Nushagak Bay crash on sandbars and rocky shores. Machines rattle the warehouses on the cannery side of the village “where the beach flattened and the boardwalks grew tall.” So many sounds; so many stories. Yet as I page through Mia Heavener’s new novel Under Nushagak Bluff under the long shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is the novel’s subtle and steady investigation of silence that most captivates me.

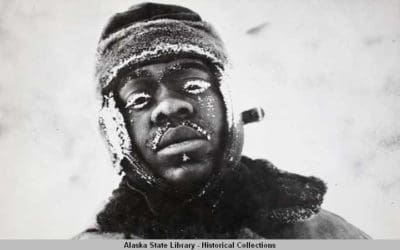

African Americans in Alaska: Black Lives Matter

From Captains on the Arctic seas, to military highway engineers, to attorneys and legislators, African Americans in Alaska came early in the history of the territory and helped develop the state as we recognize it today. Black whalers were some of the first people from the east coast to see Alaska, starting in the early 1840s . . .

Stories that Connect: Review of Mostly Water by Mary Odden

Water flows over and through the pebbles on the cover of Mostly Water: Reflections Rural and North. Water connects. Mary Odden, a long-time resident of rural Alaska, has graced us with this collection of essays written over the course of her many years in various regions of rural Alaska. Built upon each other with love, these anecdotes articulate connections between people, animals, land, sky, water, music, and memory. It’s an intimate book, and not a skimmable one. Nuggets of humor and irony randomly appear like brown sugar in the most unexpected places, and you won’t want to miss them.

Crossing Borders: Review of Floating Coast by Bathsheba Demuth

Floating Coast reads like a wave, moving from ocean to shore on both sides of the Bering Strait, from ocean to ice to land, then up the rivers, and then underground, then spilling back out to the sea. Floating Coast is a . . .

An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3

“It is an extraordinary betrayal of a national promise to care for, that the state will care for the people and its land. And . . . that the state has said “Yes, we are here, you can depend on us. Put aside your traditional ways of gathering food or of looking out for each other. Because we are here now, . . . to . . . supplant your economy with our economy now, so you can depend on it and we’ll be there.” And then for that state to disappear, is deadly. It’s really deadly.”

Review of Taaqtumi: An Anthology of Arctic Horror Stories

Dogs, blizzards, and ice dominate the dark landscape of Taaqtumi, An Anthology of Arctic Horror Stories. A supporting cast of zombies, nanurluk (giant polar bear), snowmobiles, and more, round out these horror stories from the far North. Traditional Iñuit storytelling and modern literary styles . . .

An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2

In this episode, we dive into specifics about the author’s identity and experience as a white American woman from New York City, observing rural and Indigenous Russians of Kamchatka in their day-to-day lives. We hear her reflections about time spent in rural Kamchatka, traveling with dogsled teams, reindeer herding families, and gathering wild foods. We reflect on circumpolar questions about the ocean’s fish supply after Fukushima,

While Nanabijou Sleeps: Tanya Talaga on racism and survival of Indigenous youth

Three hours north of Thunder Bay, Ontario, Armstrong had several large new homes situated on a rise above the town, each with a law enforcement vehicle parked in the driveway. Below these houses, most of the community lived in older, smaller, rundown homes. We wondered about the relationship between these officers in “Armstrong Heights” and the rest of the community, given