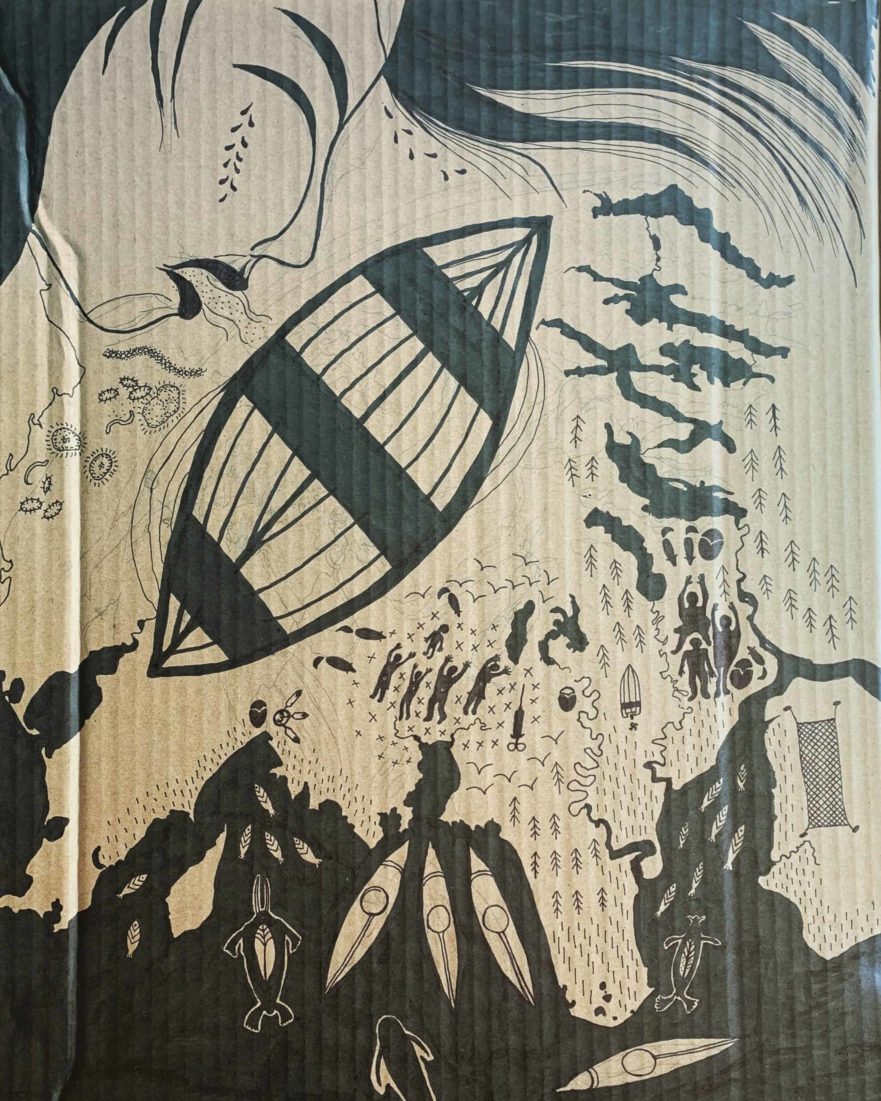

Salmonberries: An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2

(Note: Transcript of “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2” has been edited and condensed for clarity).

Listen to “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2” on Spreaker.

Welcome to our podcast: Salmonberries

Denali Sunrise Publications promotes the integrity and survival of land-based and Indigenous ways of life in the circumpolar North, especially in rural Alaska. We review relevant books, and publish rural Alaskan authors. Welcome to our podcast, Salmonberries, where we bring you stories, interviews, and discussions from across the circumpolar North to surprise, delight, and build community. For more information, please visit our website at denalisunrisepublications.com. Podcast transcripts will be made available on our website blog, and you can sign up for updates using the newsletter form at the bottom of each website page.

Introduction to An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2

This episode of Salmonberries is part II of An Interview with Julia Phillips, who wrote the debut novel Disappearing Earth, published by Knopf of Penguin Random House in May of 2019. Set in the remote Kamchatka peninsula of Russia, this book is classified alternately as women’s fiction, suspense & thriller, and literary fiction.

In this episode, we dive into specifics about the author’s identity and experience as a white American woman from New York City, observing rural and Indigenous Russians of Kamchatka in their day-to-day lives. We hear her reflections about time spent in rural Kamchatka, traveling with dogsled teams, reindeer herding families, and gathering wild foods. We reflect on circumpolar questions about the ocean’s fish supply after Fukushima, and in the context of a warming Arctic. She shares her observations about the post-Soviet religious environment, including Russian Orthodox religion and shamanism, and her experiences with various modes of transportation, including by Soviet tanks with snowmobile tracks. Her cross-cultural perspective sheds insight on the way educational systems in other parts of the world contrast with, and exceed what many Americans may imagine. In closing, the episode circles back, to the pervasiveness of enforced patriarchal, gender-based expectations and violence in the day-to-day lives of women in the circumpolar north.

An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2

Author Julia Phillips

Lisa: So you’ve spoken about identity and how it informs your understanding of culture and politics and law enforcement. In one interview you spoke about the fact that as an American writing about another country you couldn’t pretend to be anything other than American in perspective. And within that cultural gap there are also deeper cultural gaps of being a white American woman writing about white Russians or about Indigenous Russians. How did you approach those gaps? Can you talk about your experiences in Kamchatka dealing with the Even and Koryak and any other Indigenous individuals or groups? Talk about some of those interactions. What stories or experiences surprised you or challenged you and what did you learn about yourself and your worldview coming from Brooklyn?

From disconnection to community

Julia: Oof! A lot. I would say generally every single thing about being on Kamchatka surprised and challenged me. Coming from Brooklyn, my understanding of what the world looks like, how people behave, how people behave in relation to each other, how neighbors develop relationships, what sort of support or feeling of connection there was to the center, like the country’s capital or the region’s capital. I had no idea how people would relate to those things in this context, because in the context I’m in and the context I grew up in—I grew up in a center. In an area with enormous infrastructure, in an area disconnected from the natural world as much as possible that tries quite intentionally to disconnect itself from the seasons or cycles of nature, and in an area in which there is not a lot of communal responsibility-taking or feeling that we need to look out for each other in order to keep ourselves safe. So in Kamchatka, the fact that all of those things were in play, was a shock to me every single day. I was really really lucky, talk about communal responsibility and neighborliness. I was really lucky to have a lot of opportunity to sort of live with, or embed with, people in their day-to-day lives in their community.

The Beringia: Dogsled racing in Kamchatka

Julia: So, for example, I had the chance to go on a dogsled race around the peninsula, like a month long dogsled race where, I would say, half of the racers are Indigenous Kamchatkans and half of the racers are ethnic Russians, and observe those dynamics and those challenges in a really extreme setting, the setting of high intensity endurance and sport. That was fascinating. And through that race we got to visit all of these different villages because each stop of the race was in a different village, different mother village. It was a really special experience and it whet my appetite for seeing more of the villages around northern Kamchatka, villages that are often accessible only by helicopter, only in the winter, only by dogsled that don’t have paved roads going to them from the city.

{Twilight on the Tundra is a graphically written essay written by Julia Phillips about her experience traveling along parts of the Beringia dogsled race}

Traditional reindeer herding

Reindeer herders camp, near Anavgay, Kamchatka, © Julia Phillips, used with permission

Julia: I then got to spend some weeks first in Esso, which is a village in which a lot of the book centers, or some of the characters are from, about half of them. And in a village neighboring Esso called Anavgai, which is very very strongly a majority Even, and, spend some time with people in their houses you know sort of their schools their day to day lives and then be with a group of reindeer herders as they were moving their reindeer around the peninsula. The reindeer herding group I was with was a family, it’s like a family herd in which responsibility is passed down generationally. So there were three generations of that family there and then also you know their employees there helping them take care of a herd. That was such a gift to be able to be with people in a context in which their family, their home life, and their working life was so one and the same. And I got to therefore observe and be part of and be welcomed into both the homestead and the workplace and really spend 24 hours a day learning from their experience, and listening for what they wanted to share. That was a really special and unforgettable experience for me and I’m extraordinarily grateful, cause it’s obviously a big challenge for them in bringing another person into their camp. Those are really special experiences. I’m trying to think of a specific sort of anecdotes or experiences but they’re all so funny and small and wonderful.

“Everyone is extremely, extremely educated”

Julia: This is just very minor, but I think sometimes in America we have a stereotype of Russia or Russians that’s white. And by that I don’t necessarily mean ethnic Russians I mean like people citizens of Russia. Considering how we’re seen around the world, sometimes I talk to Americans who say like–someone told me the other day they they were telling me about how they were like “Oh I met this Russian the other day and he was a construction worker and he was reciting poetry.” And they’re saying this like “Can you believe this bizarre experience I had?” And I said like “Yeah, of course he was reciting poetry, you have to memorize a ton of poetry and in Russian education it’s a hugely robust educational system, an extremely educated populace.” He could recite a ton of poems because he’s memorized those poems, because that’s part of his education, because the literacy level in Russia is unbelievable. Everyone is extremely, extremely educated. And I think that like the support for the sciences, the support for the arts is unreal. That fact is often at odds with our sort of American presentation of it. And so I was telling someone the other day about when I was with the reindeer herd and I was with this sort of patriarch of this herding family. They have their groceries and their newspapers and their supplies brought in by helicopter every so often, and then they also have a sort of 4:00 p.m. check in by radio every day, they just say like, “We’re here, the herds are good, the weather is like this” and all the herds check in with each other on radio. And I remember he was reading this newspaper and he said something to me about like “Oh, your American ambassador to Russia did such and such. Isn’t that terrible?” And I said like “Oh I actually don’t, I don’t know who that is. I don’t know what he did.” and I remember the way he reacted, he was like “You don’t know who your ambassador is?” He was like “I get my newspapers brought to me in a helicopter every three weeks. And I know more about your country’s current events than you do. Are you kidding?”

U.S. Ethnocentrism

Julia: But he wasn’t even shocked in some way. He wasn’t saying like “Even I know this.” He was saying like “How do you not know this? You have all the information in the world at your fingertips and you don’t make it your business to keep yourself abreast of current events and educated?” He was like “I make it my business to know what is going on globally.” And it’s just–that’s–that’s like a, that’s a tiny thing. But that’s much more of a Russian cultural thing than it is specific to Indigenous reindeer herders. It’s just like an educated mindset. But it really cracked me up and I think about it sometimes in terms of the impression that Americans have of Russia or Russians and the assumptions I have coming in as a New Yorker, or as someone who’s on the internet all day. I think like “Oh I’m on top of my s***” no, I’m so ignorant of so much, so that was a good, that was a good moment that I like to think back on.

Lisa: Yeah, or how we think we’re so educated and that other countries aren’t, or that these communist countries where we hear all the negative things but we don’t hear some of the things that have gone well including educational systems.

Julia: Absolutely. And a sense of sort of global engagement or interest that I think we in the US are, at least in my parents and communities, are quite isolated, quite sort of ethnocentric in our understanding of relationships and events.

Traditional food gathering

Lisa: Yeah. So, speaking more about the Indigenous experiences there and reflecting on the book. I know a lot of people have talked about your descriptions of the landscape. And I think many urban people were thrilled with them whereas I from Alaska it was like, “Where is it?” Were you able to go out fishing or be involved in hunting or gathering activities beyond just the reindeer herding or while you were out there? How important were those activities? Can you talk about the role of berries and mushrooms in the food culture there, or salmon?

Picking berries in Kamchatka. © Julia Phillips. Used with permission.

Julia: Oh yeah. OK. So I did a lot of berry gathering. I’m trying to think about actual events. I did a lot of berry gathering. I did not go fishing. I did not go hunting. I watched people shoot reindeer, but that was not hunting, that was their own domestic herd. I did a lot of, this is very silly: I did a lot of eating. So a lot of eating of, you know big plastic tubs of caviar with a spoon, and a lot of different fish in all forms. A lot of smoked fish. A lot of, you know, ranges of fish types and flavors. And a lot of sort of meat that I and–Oh that’s another thing, we did a lot of gathering of wild garlic. That was it. I remember that was a very–and fiddlehead ferns, fiddlehead fern tops. That was a very big moment. A lot of jam. I imagine this is, I’m just naming to you things that are part of your day-to-day life. But to me it is special for someone to say “Oh I made this jam, I made this flavored vodka, etc. But my experience was more of the cooking and eating side of things than it was of the harvesting or hunting side of things.

Fukushima and climate change and the food supply

Julia: When I was there in 2015 there was a lot of concerns about Fukushima when it came to fish, specifically, and sort of how that would affect salmon and fish runs around the peninsula. And I’m interested. And I was there in the summertime in 2015, I wondered going into the fall how folks would sort of be reacting to gathering from the ground gathering plants and mushrooms. Did you guys have the same concern?

Lisa: You mean for the radiation here. Yes. Well now what we’re experiencing now is a lot of marine mammal die-off. And you know what I see is people say “It’s not global warming, it’s Fukushima.” And there is some trace radiation that’s been tracked and coming through. I’ve also seen good science fair projects from youth, that say well we’re getting very very small amounts of radiation. So it’s really not the alarming level that we think it is. I saw that a couple of years ago and I think given what I’ve seen of the climate over this last summer it makes a lot of sense that it has to do with temperature changes. There’s also been some plankton die off. So I think there’s concern about what’s going on in the Bering Sea and the ocean in the North Pacific. But I think personally, I suspect it’s more climate driven than Fukushima. But it’s really hard to say.

The Floating Coast: Another book about Beringia

Julia: Yeah. Have you read, are you going to read, Floating Coast by Bathsheba Demuth. It’s coming out from Norton in August, and it’s a sort of environmental and economic history of specifically, of Beringia, of Bering Strait region. And it’s really, I feel like it’d be so up your alley. As you’re talking, I’m thinking, you’ve got to read this book!

Lisa: But no, and I literally appreciate you saying that. I’m really enjoying bringing books to you know review and look at that are really relevant across the circumpolar north, and I think that those issues about bridging divides and helping people understand as I’m listening to you even just talk about the level of education. I did have an opportunity once to travel in Cuba, and I watched how the that educational system was so universal. So no matter whether you were a tourist worker or not you were literate. You were reading.

Julia: Yeah.

Lisa: Very different than Mexico for example where the hotel folks may not even know how to read. So just really different. And I think that that’s something that Americans do overlook. So I’m really appreciating all these discussions about these things. There’s such a divide here, that rural-urban divide. And it plays out in education. Gosh, now I’m starting to talk about Alaska, and I want to hear about Kamchatka!

Julia: I want to hear about Alaska all the time.

Russian Orthodoxy across the North Pacific

Lisa: One of the things about being in Alaska is that we’re so close geographically and historically to Russia, it’s a huge influence on the culture here. Russian Orthodox religion has been a huge piece of Alaska’s history and the culture of the village where my husband and my children are from, and I’m curious you know post-Soviet Union. What was your sense of the religion and how much that played a part in lives of folks when you were there. Is it still Russian Orthodox is it other, is it not really a part?

Russian Orthodox Church, Telida, Alaska © Denali Sunrise Publications

Julia: Yeah, it’s interesting. You know I will say first that the folks who are talking to me are often a self-selecting group. They’re often a group that is less religious, less conservative in–And I don’t mean conservative politically necessarily. I mean conservatives like holding on to tradition. Often the folks who want to talk to me are, are people who are departing from, sort of the establishment there. So, so I would say that there are some . . . It’s likely to me that the people I was talking to were participating less in religious life than other people on the peninsula. That there was perhaps a mainstream group I was not tapping into. I was interested in the appearance of Russian Orthodoxy across the peninsula. It has, there’s a buildup; there’s like a very recently built Russian Orthodox Church in the capital city that had a lot of money going to it and a lot of money sort of fund the pockets of those building it and those approving it. The state and the church in contemporary Russia are extremely intertwined. When it comes to wealth and policy there’s a lot of, they’re both seats of corruption, I would say. And that is continuing into the building of the church and church practice, church leadership in the capital city. I say that, also saying that I had the great good luck of meeting, actually through that dogsled race, some Orthodox priests who were wonderful. Absolutely wonderful. Really like, men of god, you know, people who are very much living as spiritual leaders, as community leaders, in really essential and interesting ways. Obviously the place of religion in the Soviet Union was minimized, I would say, as a general way to put it. My perception is that religion in contemporary Kamchatka is not robust. And yet there is of course, a Russian Orthodox presence, a growing, a visibly growing Russian Orthodox life, that I imagine will continue to grow into the future.

Some shamanism has survived

Julia: There’s also a few folks in villages and an Indigenous community talking about continuing and growing their shamanic traditions. Shamans under the Soviet Union were extraordinarily repressed; Stalinist and purged. It was seen as like an anti-Soviet activity to have shamanic or animistic traditions of shamanism, traditions of animism were seen as anti-Soviet, and their practitioners were murdered and jailed. There has been some preservation of those religious traditions and spiritual traditions. And folks there are folks on Kamchatka that I spoke to that are trying to sort of strengthen and grow them. But the state repression there has been mighty.

Lisa: So that it continued–

Julia: Yeah, that it continued at all is extraordinary. But it is a very narrow shadow of what it once was. So there’s these different spiritual lives happening on Kamchatka in my perception, and they’re fascinating because they are also operating in a space that was vacated by a great national faith which was a faith in communism and socialism and the loss of that sort of national identity which was, had a spiritual fervor to it, is huge. And different religious traditions are sort of working within that vacancy and trying to grow.

Getting around: Soviet ‘Hoods’

Lisa: Can you talk some about your experience of traveling between communities on the peninsula, like modes of transportation and your emotional response, and safety. Anything else. What surprised you the most?

‘Hood’ with snowmobile tracks, Kamchatka © Julia Phillips, used with permission

Julia: Yeah I had a lot of I had a lot of fun with variety of transportation and travel between communities by car and by bus and by snowmobile and by tank. They call them the hoods. It’s like a go-everywhere, retrofitted tank, Soviet tanks that then have snowmobile tracks, enormous snowmobile tracks on them, and so they can go over snow and ice and slush and you get in through a hatch in the top. It’s very exciting. I traveled by helicopter and by small plane. I never traveled for more than a few feet by dogsled because people were like “Oh, that’s my dogsled. You can play around, but you’re not going anywhere.” Which was extremely correct! Oh by horse. A lot of traveling by horse. So a lot of different modes of transportation.

It’s complicated: transportation safety for women

Julia: This book is about violence against women and about an underlying current of dread or of fear or a kind of self-policing or policing by community constraint by community that occurs when you are the target for violence and target for oppression. That for example, many of the characters, especially one of the Indigenous Even women characters (Ksyusha) in particular, is extraordinarily constrained by the constant threat under which she lives. She is told by her community, by surrounding media “You are always at risk, and you must be careful all the time because of that, you can’t act in this way. You can’t behave in this way you can’t be this way you can’t speak this way, if you want to keep yourself safe.” The book is really preoccupied with that and I think it’s a reflection, I know it’s a reflection of the state in which I was certainly living on Kamchatka, but also in which I live my life generally. I think my experiences of feeling at risk in Kamchatka were emphasized because I was not a citizen, I was an outsider, I was very young and I had–the support structures in which I, which I usually have, were not there. And so there was a level of risk that came from that, that was emphasized. But these are not risks that are particular to Kamchatka at all. The feeling of sort of threat or danger of being targeted, any people have who are the target of violence. You know, whose gender or race or ethnicity or religion is a target of violence. Constantly that it’s something that you live with in your body and in your experience. So a lot of what I think about moving from community to community, I was often with groups of men because they had a lot of mobility. Groups I could embed with were groups that were dominantly men. And, I’m trying to think of how best to put words to this. In my experience part of being a woman is a reinforced fear of threat of violence from men. Or part of being a foreigner or an outsider is a reinforced fear of threat of violence from insiders or from people who have legal status who can wield it over you or–and so, in those, in those settings. Those fears for me were very ratcheted up. And I say that again, acknowledging how incredibly hospitable and generous and welcoming and caretaking everyone I met was. I will modify that and say almost everyone I met was. There are moments where you think like, “This better turn out OK because if it doesn’t turn out OK I’m gonna be in a real, a real sticky situation” And that is something that I feel about 75 times a day here in Brooklyn!

Lisa: Oh yeah. Yeah I hear you!

Julia: I think you know what I mean.

Lisa: Yeah! And it’s interesting because it’s such a universal theme in your book and in our lives, that theme of gender-based violence. And when I asked you about transportation it really wasn’t even the thing that came to mind, because I’m thinking about the stories I’ve heard about the planes there and how, how in Alaska, people don’t wear their helmets on four wheelers, and you know, like thinking about coming from Brooklyn, New York to these sorts of rural modes of Northern transportation and–

Julia: Oh my God, yeah.

Lisa: It circled back to the issue of gender-based violence and how we constrain our lives. And it’s such an issue.

Kronotsky Reserve, helicopter. © Julia Phillips, used with permission

Julia: That that makes me laugh because you’re honestly, I’ll tell you, that coming from a context in which I’m so ignorant about those kinds of transportation, if I were more informed, I would, I’m sure I would have been like “What–this is actually a big problem—like this is like—” there’s a rate of helicopter crashes on Kamchatka that is not immense, but like, it’s not great. And Russian air travel in general has like oh, let’s, I’m just gonna say, not as strong a safety record as for example U.S. air travel. And you know, I think if I’d been more informed about those things, or more sort of, less foolhardy, I think I would have been much more attentive to the dangers. But I was just like “Let’s go for it!”

End of “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2”

That concludes this episode of “An Interview with Julia Phillips.” Please subscribe to our podcast, Salmonberries, to be notified when the next episode is released. To read podcast transcripts, or our book review of Disappearing Earth, please go to our website at denalisunrisepublications.com/blog. Interspersed with transcript postings of the episodes of “An Interview with Julia Phillips,” our website will be posting reviews of some important books by Indigenous and other authors from the circumpolar north. Books such as Seven Fallen Feathers and All Our Relations, by Tanya Talaga, and A Dream in Polar Fog, by Yuri Ryktheu, are relevant to understanding current issues of cross-national concern in the rural north.

Our online bookstore sells many of the books that we discuss, and offers a standard 5% discount. For periodic coupons of up to 20% off to buy books we review, please sign up for our newsletter at our website, denalisunrisepublications.com. Thank you for listening in to this episode of Salmonberries.

Remaining episodes of “An Interview with Julia Phillips” coming soon

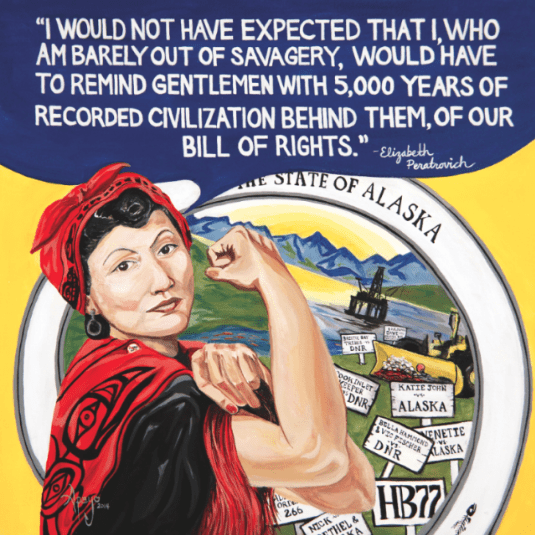

If you enjoyed “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 2,” please tune in to the remaining episodes by subscribing to our podcast, Salmonberries. This extensive interview with Julia Phillips touched on many specific themes that intersect between Kamchatka and Alaska, providing international insight on the rural/urban divide, changing sources of food and energy, murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (#MMIWG), the experience of gender and culture and ethnicity in the north, and of course, books (see below). There will be a total of four episodes. [11/19/19: Go to episode 3 transcript and link to podcast]

Newsletter notification and link will go out as each recording goes live and the corresponding transcript is posted. (Newsletter signup form is at the very bottom of every website page). If you’d like to buy the book and read it first, it’s available at our online store (click on the “buy this book” link in the box below), or buy the book at your local bookstore. For more information about justice issues and resources in Alaska, please check out our page, Resources: Freedom and Security. See also our blog post, “Indigenous Women Authors: Review of The Round House by Louise Erdrich” for more on the topic of representation of Indigenous women in literature.

Podcast download links

Salmonberries can be accessed by clicking on any of the below links:

Authors & books, books, books

The following is a list of some of the authors and books mentioned throughout the course of the interview. Links provided to books available through our online bookstore.

Alice Munro

Leo Tolstoy (War and Peace, Anna Karenina

Louise Erdrich (The Round House, Plague of Doves)

Tanya Talaga (Seven Fallen Feathers, All Our Relations)

(For more information on the topic of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) in North America, see our resource page, Freedom and Security, (link there to current newspaper coverage of the two-tiered justice system in Alaska as well as Amnesty International report and Canada report on MMIWG) and read The Round House by Louise Erdrich. Related scholarship has also been done by Canadian Ojibway journalist Tanya Talaga, see her books Seven Fallen Feathers and All Our Relations.)

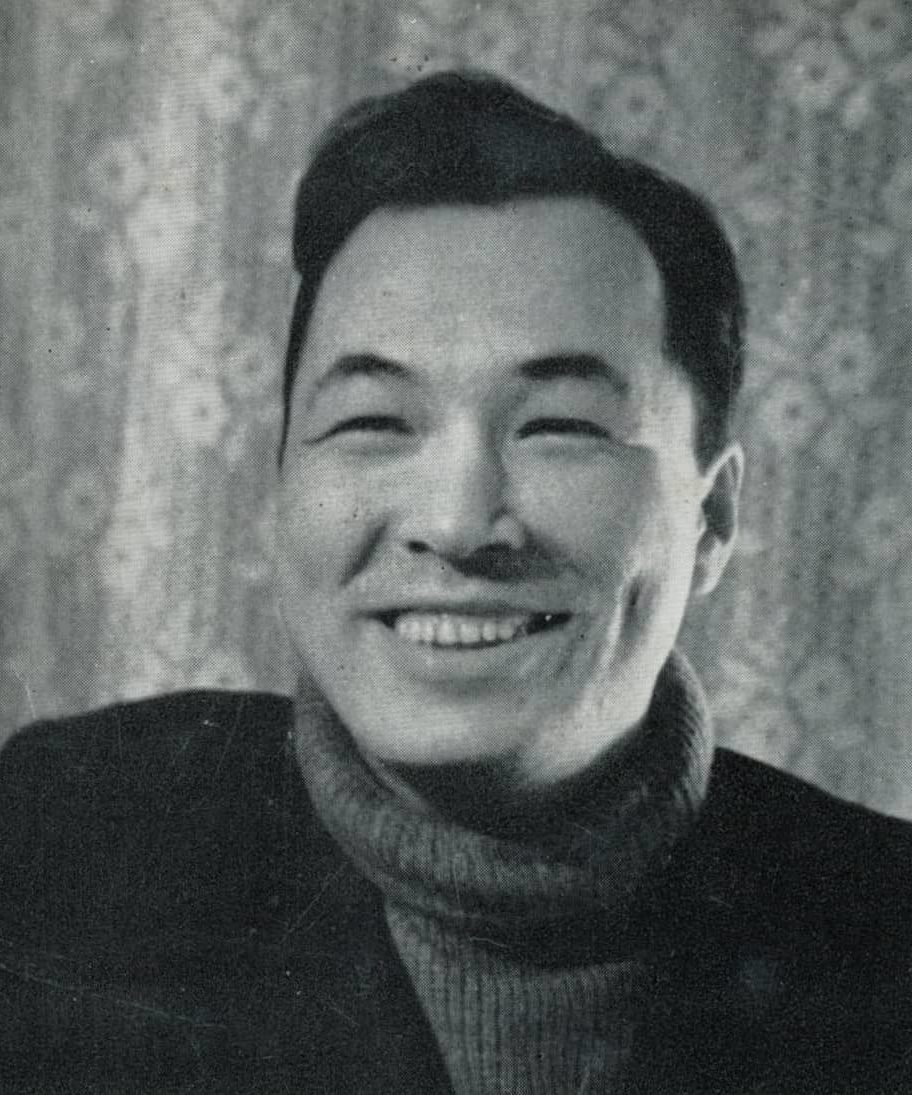

Yuri Rytkheu, a foremost Indigenous Russian author from the Chukchi Peninsula, wrote several books that have been translated into English. A Dream in Polar Fog (translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse) and published by Archipelago Books, translation © 2005, originally published in Russian in 1968. Ryktheu also wrote the Chukchi Bible (also from Archipelago Books, © 2011). Coming this fall from Milkweed Editions is a third book by Ryktheu, translated by Chavasse, titled When Whales Leave.

Floating Coast by Bathsheba Demuth, check out the book review written by Julia Phillips for the New York Times. Published by W.W. Norton & Company, © 2019

Other recently released books mentioned during the interview:

Losing Earth by Nathaniel Rich

Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells

Kamchatka Picnic. © Julia Phillips

Denali Sunrise Publications Bookstore

Click on the button below to purchase this book in our store

(or buy it at your local independent bookstore)