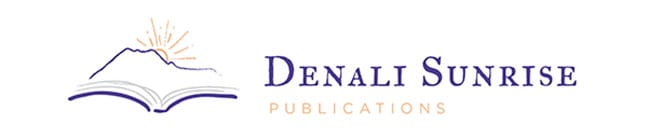

Artist/author Amber Webb describes her work above as “Sketching the story of how the Spanish Flu pandemic hit Bristol Bay in 1919 and changed the region. The map is about Goodnews Bay to the edge of Nushagak Bay. It also includes the lakes. Not a very accurate map, but it’s symbolic. They say that people from Kulukak relocated to Kanakanak, Togiak, Manokotak and Aleknagik because so many people died. I know one of my great-grandmothers was from Kulukak, but moved to Kanakanak. I don’t know if it was during this pandemic. We are resilient people.”

Editor’s Note:

This is the second of two blog posts featuring rural Alaskan creative responses to the history of pandemics in the Bristol Bay region of rural Alaska, where as many as 40% of the rural population perished in the 1918 flu pandemic. While the influenza epidemic stands out in Bristol Bay history, it was only one of many pandemics to devastate the region. To understand the complexity of people’s feelings about COVID-19 in rural Alaska, we must also understand how the history of influenza in 1918 set the stage for other, ongoing epidemics. While the physical risks of COVID-19 are very real, for most of rural Alaska they still represent a significant potential loss, while the risk for death from suicide, violence, or substance abuse remains high and may be increasing with the isolation of COVID-19.

Yup’ik, Iñupiaq, and other Indigenous people of Western Alaska continue to live on the land and maintain their languages and traditional way of life, despite tremendous loss. Amber Webb’s complex story art uses paint on scraps of cardboard and plywood to convey the tensions that exist in Western Alaska, between the challenges of surviving ongoing epidemics, and the resilience of a culture with deep connection to place, across time.

Multiple pandemics of rural Alaska: Artist/Author Amber Webb makes connections

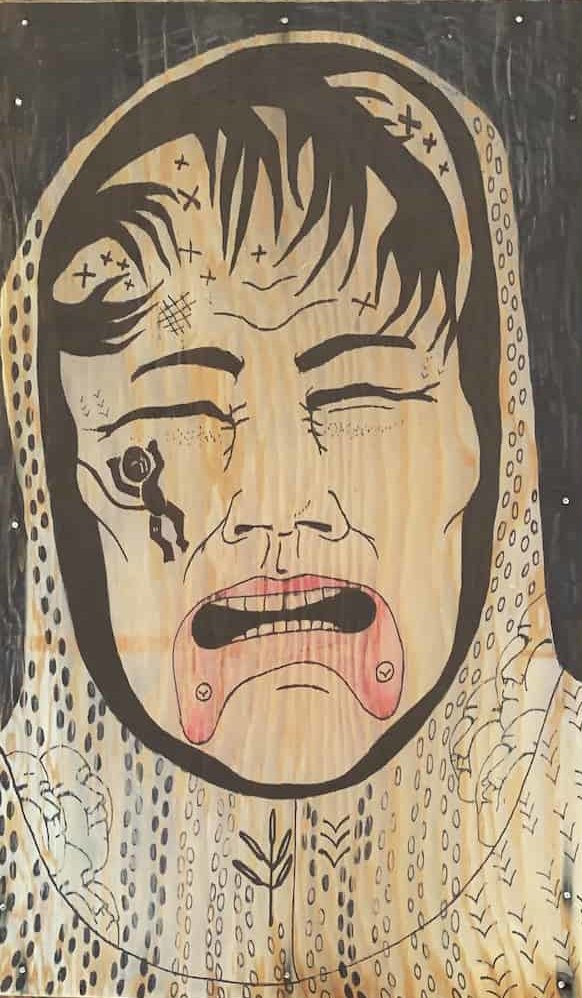

This one was a prayer for anyone who can’t be safe during the pandemic, that they find protection and health. This was at the beginning, but there was indeed a stark increase in the ongoing epidemic of murders related to domestic violence in Alaska and all over Indigenous communities. Many of us know the increased isolation aggravates this ongoing threat.

Prayer for those without a safe home during the pandemic

This drawing is a wood and ink prayer for everyone, especially every Native woman, who isn’t safe at home or who has no home in which to seek refuge. During this time of rising global tension, there will be people who are separated from their support networks and the services needed to protect themselves. If you are one of these people, know that there are millions of us who stand with you and pray for your safety. May your ancestors surround you and watch over you. May you find a way to be as safe as possible.

You are so important in this world.

You are so important in this world.

In response to increases in suicide in the Bristol Bay region since COVID-19: To every native man (or woman) who feels like this on the inside and doesn’t talk about really awful things that you’ve witnessed or experienced: Your traumatic experiences don’t make you less of a man. You are allowed to heal in whatever way you need to. Sometimes we carry the feelings of the traumatic experiences of our mothers and fathers several generations back and it’s difficult to understand why we carry so much pain. Suicide has left so many tears in the fabric of our societies. Please, remember that there are a thousand possibilities, paths that only you could walk. There is a path forward. There are so many things that only you know. You are so important in this world.

Abuse is a symptom of colonial oppression

Traditional teachings can help prevent abuse and heal trauma

I’ve been thinking about ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) and how the limbic system, when changed by trauma, destroys our family systems. People can heal from this trauma and take their place in traditional society. Every person who practices the old teachings and tries to learn more of those teachings is healing our collective world. Everyone is capable of healing, but if someone behaves abusively toward you, leave them to find their own healing and go find your own healthy life. The elders tell stories that are admonitions about how to treat people. Men in their stories who mistreat women have bad things happen to them because they upset the natural order of things. Women who scheme and manipulate also meet an ill fate. Even in war times, men were taught not to hurt women. Abuse is something introduced by a complete upheaval of our social structure and value system. It is a symptom of colonial oppression.

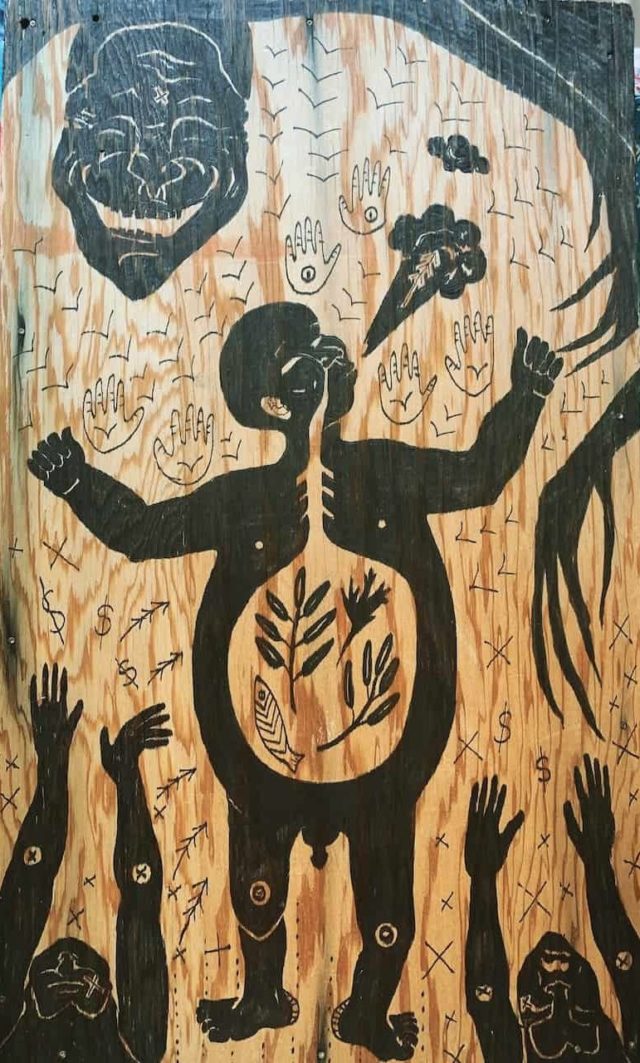

In response to increasing issues related to substance misuse disorders

Sending love to anyone who is struggling with substance abuse

In the upper left corner is the spirit of methamphetamines. The man in the middle is the spirit of the Aleknagik ancestors blowing the meth away from the people who are suffering. This is an acknowledgement of the power of meth to hurt our people and a wish that all native people who need it find healing so that they can draw from the power of identity and of their ancestors instead of the sick power of substance abuse. Sending love to anyone who is struggling.

Editor’s note, continued:

Influenza decimated Bristol Bay and much of rural Alaska in 1918

Around 1918, pandemic influenza claimed the lives of at least 50 million people worldwide, notably killing many young healthy people, within a matter of hours. Parts of remote Alaska may have been harder hit than anywhere else in the world, with a death rate as high 90% in some communities. The grief of widows and widowers, orphans, and the subsequent imposition of reorganized family and community structures, continue to cast a shadow through multiple generations. The book Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World, notes that as many as 40% or more of Alaska Native people from the Bristol Bay region of Southwest Alaska died in the 1918 flu. In some villages, nearly all the adults died within a brief period of time. The Alaska Packers Association’s Report on 1919 Influenza Epidemic for Naknek, Nushagak, and Kvichak Stations, describes the impact of the epidemic on the region. Most of the Alaska Native residents of Dillingham today descend from the orphans left behind by influenza. Over 80% of those who died of the influenza epidemic in 1918 were Alaska Native. In 2018, the State of Alaska analyzed the flu data from 1918, noting that a translated death rate in contemporary terms would have been equivalent to nearly 12,000 Alaskans (9600 Alaska Natives).

Other writers and artists of Western Alaska

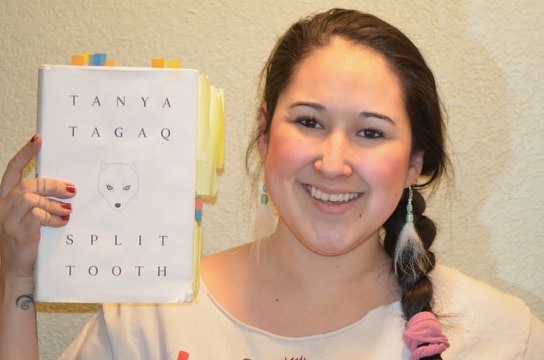

The book reviewed in the first of these two posts, Under Nushagak Bluff, emerges from this quiet backdrop of loss in the Bristol Bay region of Western Alaska.

COVID-19 is only one among many pandemics that rural Alaska has struggled with in recent years, and some of the other pandemics remain more lethal to rural Alaskans. This may change over the coming winter. Regardless, we must be mindful that deaths from both COVID-19 and other, ongoing, epidemics will impact families and communities going forward. See the book Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being by Harold Napoleon (of Hooper Bay in Western Alaska) for a direct discussion of the devastating multi-generational impact of pandemics on Western Alaskan communities that were especially hard-hit.

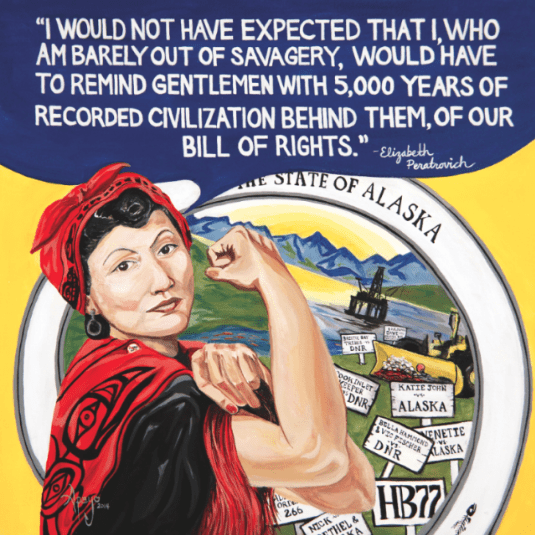

The Alaska Native people of Bristol Bay have survived past pandemics, and are surviving contemporary ones as well, through maintaining their way of life. The artwork on the cover of Under Nushagak Bluff book is by Apay’uq, another talented, thoughtful artist of Bristol Bay. Her art also appears on the cover of Fighter in Velvet Gloves, and her colorful, joyous murals grace buildings in Dillingham and around Alaska.

For more stories about how the people of the far northwest of Alaska responded to the 1918 flu pandemic, also see this review of Menadelook.

Memory of 1918 motivates rural Alaskan caution around COVID-19

While COVID-19 does not yet appear to approach the scale of lethality of the 1918 influenza pandemic, it is a new virus, it is rapidly evolving, and with inadequate efforts to mitigate, it spreads exponentially–much faster than most people comprehend. It was the second wave in fall that took the most lives in 1918, and we are just entering fall–and as this post goes live, our rates are skyrocketing in Alaska and nationwide, and hospitals are preparing to overflow. While we all brace for the coming wave of COVID-19-associated illness and death, let us remember the haunting shadow still cast in rural Alaska by losses from the 1918 flu. Multiple waves of other epidemics, with their ensuing silences, continue to reverberate. Rural Alaskans are motivated to actively protect their communities from lethal pandemics, viral or otherwise, and must sometimes make difficult choices between different dangers. An understanding of this complex history is absolutely necessary for anyone making or recommending policies with regard to COVID-19 in rural Alaska.

Masks are a primary prevention tool where frequent handwashing and physical distancing are particularly challenging. Quarantines, while harsh, are a time-honored means of protecting communities. If you must travel to rural Alaska during the COVID-19 pandemic, please honor all tribal and community mandates and requests, to reduce risk of transmission in the communities you visit.

Resources

If you are in need of assistance and unsure who to call, Alaska 2-1-1 can be a starting place.

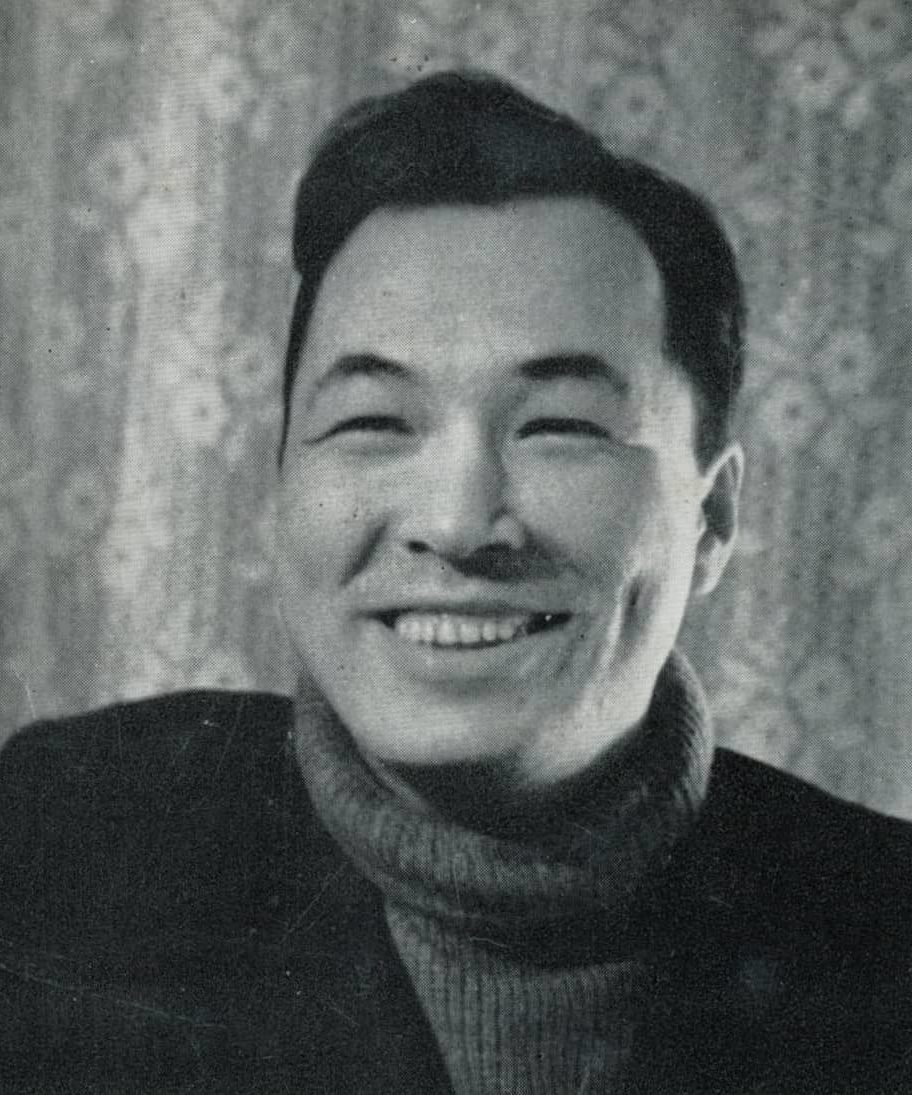

Artist Amber Webb

Artist Amber Webb

Amber Webb is a Yup’ik artist/activist from Dillingham, Alaska. After graduating from UAA in 2013 with a BA in woven fibers and a minor in history, she worked industrial jobs while designing apparel featuring Yup’ik language in solidarity with language reclamation efforts. In 2018, she was awarded a Rasmuson Foundation Individual Project Award for a 12-ft. qaspeq to honor Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) in North America. Her work visually explores the effects of colonization and the evolution and strength of Indigenous people after genocide and intergenerational trauma through portraiture and textiles. She is exploring pictorial Yup’ik storytelling to communicate contemporary stories of oppression, historic trauma, resilience, humor, changing climate, motherhood, and resistance; some of these works are posted above. Amber was Choggiung Ltd. Shareholder citizen of the year, Bristol Bay Native Corporation Citizen of the year and also received the Walter Sobeleff Warrior of Light Award from Alaska Federation of Natives in 2019.

Her most recent work, the Qaspeq Project, has been featured on KTUU, KTVA, First Alaskans Magazine, First Americans Magazine, in the Juneau Empire, Alaska’s News Source/NBC Channel 2 News, and most recently on The Tonight Show. The first qaspeq in the series was purchased by the Anchorage Museum. The second qaspeq was funded by the Rasmuson Foundation. It was most recently present for conversations at the annual Alaska Federation of Natives gathering in 2019. The larger qaspeq was also displayed at the state capital building in Juneau, Alaska during testimony for HR 10, a resolution in support of Savannah’s Act, Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and increased financial support for law enforcement in rural Alaska.

You can follow Amber Webb on Instagram @imarpikink. She has a few items posted for sale at Collective49 Marketplace.

The Qaspeq Project