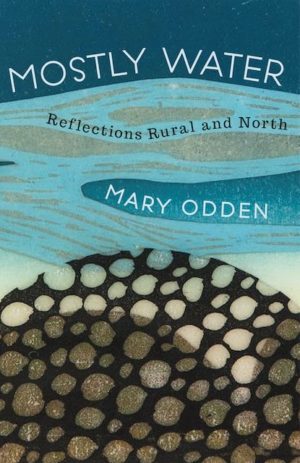

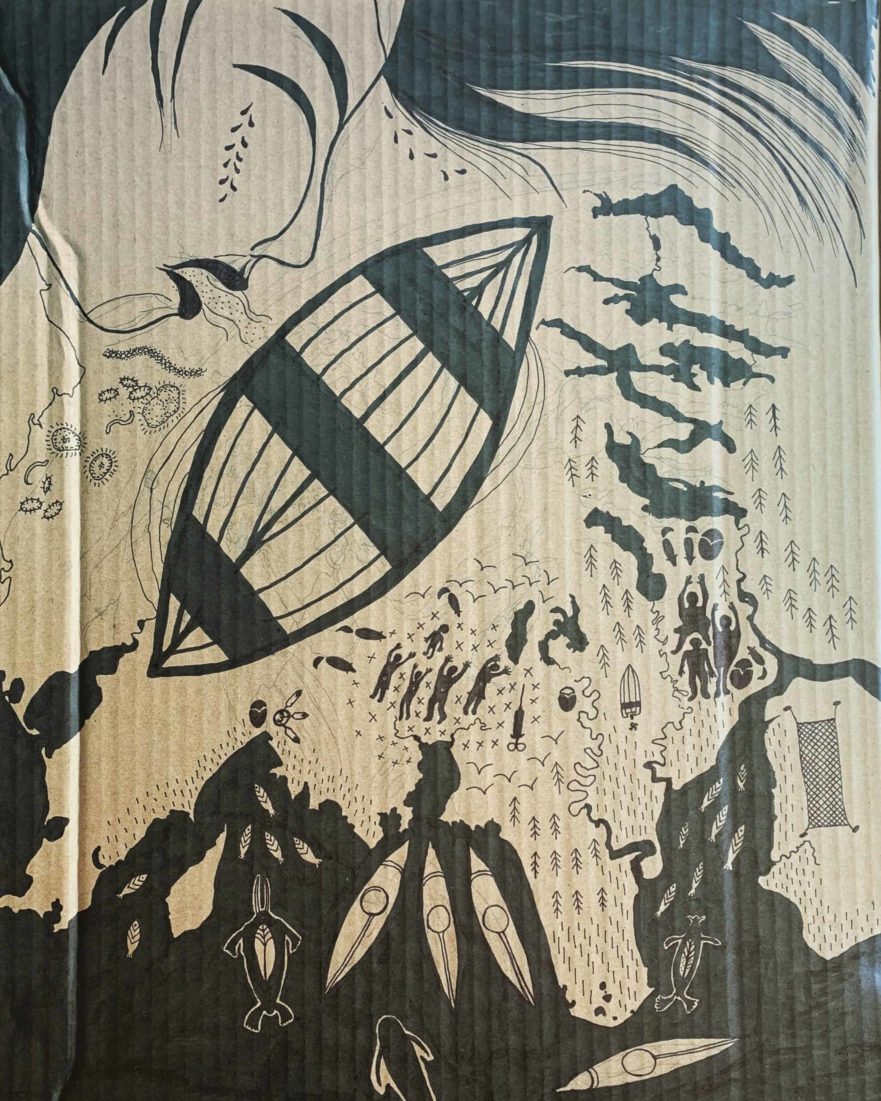

Water flows over and through the pebbles on the cover of Mostly Water: Reflections Rural and North. Water connects. Mary Odden, a long-time resident of rural Alaska, has graced us with this collection of essays written over the course of her many years in various regions of rural Alaska. Built upon each other with love, these anecdotes articulate connections between people, animals, land, sky, water, music, and memory. It’s an intimate book, and not a skimmable one. Nuggets of humor and irony randomly appear like brown sugar in the most unexpected places, and you won’t want to miss them.

Mary Odden’s reflections span a lifetime of living in the rural West, from her origins in Eastern Oregon to her adult years throughout rural Alaska.

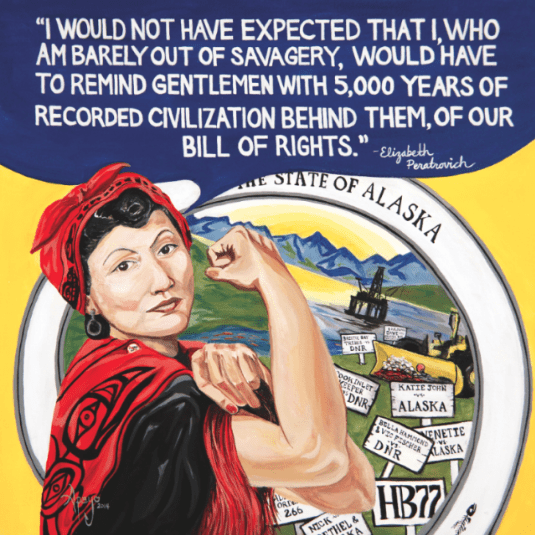

Neither a straightforward memoir, nor just a book of natural or regional history, Odden offers her collected wisdom at the intersection of diverse cultures, geographies, and eras. Many great North American writers have touched on these subjects. However, both her perspective as a woman, and awareness of settler status, shape this collection in distinctive ways. Universal themes of identity and connection flow throughout, challenging us to acknowledge, with feeling, that we humans are not the only important life here.

Identity

Identity

The opening essay, “Going to the Hills,” explores Odden’s formation as a woman in rural eastern Oregon. Odden goes on in later chapters to explore questions of identity in relation to where we come from, and where we settle. Throughout the book, these questions are touched upon with humility and kindness. How does our identity shape our understanding of living on the land in community with Indigenous residents, who tolerate settlers with more generous equanimity than  we deserve? How does this generosity teach, and change, and humble us? How does our identity shape our awareness as we navigate remote rivers in Alaska, by air or by boat? Can the awareness of an Alaskan settler change over time, in navigating rivers, from using maps, to recognizing major landmarks, and finally, to reading the smallest riffles in the water?

we deserve? How does this generosity teach, and change, and humble us? How does our identity shape our awareness as we navigate remote rivers in Alaska, by air or by boat? Can the awareness of an Alaskan settler change over time, in navigating rivers, from using maps, to recognizing major landmarks, and finally, to reading the smallest riffles in the water?

Expanding our sense of self with people

In “Shape of an Egg”, Mary Odden traverses the incredible journey of sleep-deprivation and emotions that is parenting. This requires an almost unimaginable expanse in one’s conception of self to include another human being. From here, “People on the Ferry” relates the joy of connecting with strangers while traveling on the ferry system, learning about food traditions in other parts of Alaska. In “Sound of a Meadowlark”, Odden comes straight out again with a core theme of her work—“If I walk outside, the slightest flower that blows reassures me—not that I won’t die, but that I am not the center, and therefore my powerful, wonderful, dangerous eyes will not destroy or encompass the mysterious nature that sustains me.”

Dogs, Music, Memory

“My Life in the Service of Dog” addresses our identity in relation to the dogs in our lives, attempts to look at the world through their senses. The book ends with two powerful chapters; one looks at how music shapes identity, and connects people across divides. The final chapter examines the shift in identity under the weight of memory loss in a small community, where friendship softened the decline of aging.

Kitchen Connections

Each chapter is followed by a brief sojourn to Odden’s kitchen, where we learn of foods adapted from far away and nearby, from lingonberry sauce to lefse. These stories carry culinary traditions through generations, across time and place. They remind us of the way the North breaks your heart with kindness.

Reconnecting to the Land

History has typically been told in relation to human beings, which misses the grand picture of so much that goes on beyond our ken. Recent books from major publishing houses, such as Floating Coast by Bathsheba Demuth, and 2019 Pulitzer Prize winner Overstory by Richard Powers, also work to de-center the role of humans in history and geography. While these attempts aren’t new, their widespread acclaim may reflect a readiness for these ideas that hasn’t previously existed among the majority of readers.

De-centering humans: “Who am I in relation to the things that don’t need me?”

Rural Alaskans, (and really, most rural Americans), understand that we aren’t at the center. Some Alaskans are born into a culture and heritage that understands how little power we have over our plans, and learn this growing up. Settlers who don’t understand this, learn it quickly upon moving to Alaska. This is simply a requirement for survival. We are not in control of our schedule: weather, water, ice, animals, fire, earthquakes, even something so small as mosquitoes, or a coronavirus—the power of the earth is omnipresent and commands our utmost respect. In the opening to chapter 2, “March,” Odden asks, “Who am I in relation to the things that don’t need me?” The humility of this question is, again, a significant theme of this book—yet there are deeper takeaways stirring beneath.

Music connects like water

Hobson fiddle

“St. Anne’s Reel,” toward the end of the book, ambles through a square dance to tell layered stories about music in Alaska. For those unfamiliar with these histories, it takes some attention to follow her rhythm, but it’s worth the effort. She introduces us to new concepts—for example, how many of us have heard of shape-note music? And history—did you know about Iñupiaq fiddle maker Frank Hobson? She helps readers trace the paths of specific songs, such as Wagon Wheel, which connect people across villages throughout the North. Odden tells of the rise of Athabascan fiddling up the various Alaskan rivers, the hybridization of their talents through fiddling festivals, and of modern concerns about who will learn the old tunes. She explores the uncomfortable boundary between respectful appreciation, and concerns about appropriation from outsiders, which can sometimes include settlers who’ve lived and fiddled in Alaska a long time. This chapter is a powerful tribute to the importance of music in memory and the deep transmission of culture—including cultures of respect and connection.

Memory and Identity

While Milan Kundera’s book Identity stands out in literature for describing how memory and friendship shape a human, it is a starkly urban story. Odden’s essays explore questions of identity with a warmth and love familiar to rural communities, which come through in a crescendo in the final chapter, exploring identity through the depths of senility. Odden writes,

“Friendship is to some extent being a mirror for your friend; your regard for her and your memories of experiences and conversations constantly reinforce her picture of her past self, her continuity, her creation myths. If memory is like a wool sock—wearing out where you walk on it—then when the heels and the toes go, a friend can weave some yarn back and forth over the hole. M—— couldn’t remember if she’d had coffee in the morning, but if I came over and I reminded her that she was always a person who liked coffee in the morning, she’d answer back with a policy statement on coffee in the morning, and on tea in the afternoon, and it led her to the stove and the water and the tea and the honey of the present moment.”

Mary Odden paints the tapestry of friendships and acts of caring that keep a beloved community elder at home in their body and spirit as well as their house. Although the particulars of taking care of food and chores are part of this, the laughter and moments of shared memories are integral here. This chapter is the kind of loving voice of continuity that many of us need to hear right now.

Savoring Mostly Water

The process of reflection this book engenders is worth the time you put into it. As a settler to Alaska, who grew up in a city without a sense of the aliveness of the earthly world around me, I found much to appreciate. More than once, as I read, I found myself wondering, What if the things we think don’t need us—actually do? And from that stepping stone of wonder, life in connection with everything around us, begins.

An intimate treatise on identity, rooted in both the particulars of Alaska and the broader landscape of the American West, Mary Odden’s new book, Mostly Water: Reflections Rural and North, forges necessary connections in our hearts and minds.

Author Mary Odden

Author photo © Alexa Wray

Mary Odden came to Alaska in the 1970s. She worked on the Yukon, Kobuk, and Kuskokwim Rivers at seasonal jobs including wildfire and aircraft logistics. Selected columns from Mary’s years as editor of The Copper River Record have been published as Who’s Driving – Windshield Time with a Small Alaska Newspaper. Her essays about Alaska places and communities have appeared in various publications including The Georgia Review, Nimrod, and Alaska Quarterly Review. Boreal Books, an imprint of Red Hen Press, published this volume of Mary’s memoir essays, Mostly Water, in the spring of 2020. She lives with her husband Jim in Nelchina, Alaska.

Her website is as entertaining and layered as her book. So is her YouTube video about the book. Below that is the YouTube of the recorded live launch, a little over 1 hour, hosted by Boreal Books and Homer Bookstore.

Photos of violin, dogs, preserves © Mary Odden

Buy this book

If you would like to purchase this book, click on the buy button to go to the detail page for this book at the Denali Sunrise Publications bookstore, which sells quality books relevant to rural Alaska online at a 5% discount off retail, including many of the titles featured on our blog.

For coupon codes offering greater book discounts, please subscribe to our newsletter.

Thank you for a very insightful and well written review. It makes me want to read this book, as it offers the opportunity to delve deeply into experiences with which I am unfamiliar. I enjoy broadening my perspective and feelings of awareness and caring through the eyes and experiences of those immersed in fields they love – an expansion that most Nurture through travel and generously shared here for those of us who travel via armchair.