Salmonberries: An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3

Julia Phillips is a National Book Award Finalist!

(Note as this post goes live: Julia Phillips is a National Book Award Finalist for her debut novel Disappearing Earth. Winners will be announced November 20, 2019. Transcript of “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3” has been edited and condensed for clarity. To read or listen to the first two parts, go to Part 1 and Part 2; to listen to the final episode, sign up for our newsletter to be notified of its release).

Listen to “An Interview With Julia Phillips, Part 3” on Spreaker.

Welcome to our podcast: Salmonberries

Denali Sunrise Publications promotes the integrity and survival of land-based and Indigenous ways of life in the circumpolar North, especially in rural Alaska. We review relevant books, and publish authors of rural Alaska. Welcome to our podcast, Salmonberries, where we bring you stories, interviews, and discussions from across the circumpolar North, to surprise, delight, and build community. For more information, please visit our website at denalisunrise.com. Podcast transcripts will be made available on our website blog.

Introduction to Episode Three

This episode is Part 3 of An Interview with Julia Phillips, who wrote the debut novel Disappearing Earth, published by Knopf of Penguin Random House in May of 2019. As of this recording, it has been longlisted for the National Book Award, and the Center for Fiction, First Novel Prize. Set in the remote Kamchatka peninsula of Russia, this book is classified alternately as women’s fiction, suspense & thriller, and literary fiction.

In Episode 1, Phillips discussed the structure of the book, her literary influences, and the issue of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls, which is woven into the novel in a way that raises awareness of media’s complicity in this problem. In episode 2, we discussed how identity frames point of view, and then explored her observations and reflections regarding food harvesting, education, religion, and transportation, during the time she spent in rural Kamchatka.

In this third episode, we deepen discussions of society’s behavioral expectations for women, including some surprising differences and similarities across cultures. We talk about the “second shift” women endure across cultural and national identities. We examine the common thread of colonialism which has impacted Indigenous cultures in both Russia and the United States. Phillips reflects upon the struggle of Indigenous Kamchatkans to retain language and traditional way of life. She reminds us that the infrastructure buildup during the years of the U.S.S.R. provided enormous economic security to rural Kamchatkan communities, which collapsed with the fall of the Soviet Union. We reflect upon the privations experienced in rural Kamchatka after Soviet support evaporated, complicating current sentiments about the Russian State. In closing this episode, Phillips’ recollections of stories told by Indigenous Kamchatkans of the post-Soviet era, serve as a cautionary tale to Alaskans of the dangers rural communities here face in our current era of declining oil revenues.

An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3

Author Julia Phillips

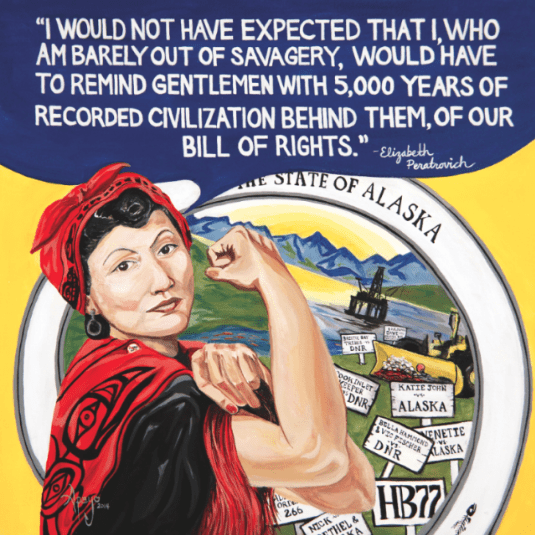

Intersections: The State, ethnicity, and gender-based violence in the North

Lisa: So, on the topic of gender-based violence and how it plays out in so many ways in your stories and in our lives, would you talk about some of the similarities and differences you noticed as an American observer in Kamchatka? And I mean both between the countries and between the different identities of people within Russia or Kamchatka specifically. So, for example, was that sense of gender-based violence different for a young Even woman than for the Russians in general, or were there differences or similarities in that way?

Julia: I feel very positive that there were differences between, for example, an Even young woman’s experience and an ethnic Russian’s experience when it comes to gender-based violence. I will also say that because of my sort of American vantage point, so much of what I perceive falls under the large umbrella for me of Russian cultural difference, Russian cultural–you know sort of like being a–growing up in the Russian state. How does that affect one? And so it was difficult to delineate sometimes on a group level, what is specifically ethnic Russian within Russia, and what is specifically Even or Koryak or Itelmen, within Russia. Unless those experiences were sort of clearly marked or named.

Whether gender expectations are explicit or implicit,

Julia: The experience of gender and specifically–In Russia–it’s very fascinating. Russians are often much more explicit, much more straightforward in naming what is happening or talking about what is happening. There’s a lot of subtlety and stuff that’s hidden and stuff that’s not talked about and stuff that sort of talked around, but on a surface level much more straightforward, like much, much, much more straightforward. Whereas I think there’s a sort of make nice or superficial small talki-ness of Americanness that plays out differently with different people, different ethnic groups, different sort of regional understandings. In my understanding of, my perception of what America is, Americanness, is there’s a sort of like superficial, like you smile, you make nice you don’t really talk about it. And then underneath that, there’s all this roiling aggressiveness, and like, violent rage. So Russia is a great place to go as a foreigner, as an American, because people name things much more in everyday operations.

Lisa: Would you give an example?

Julia: So for example, when people talk about gender in Russia, people would say to me, “Don’t lift that. It’s too heavy and you are too weak because you’re a woman and you cannot, women cannot do that, you’re going to hurt your womanly parts. You will not be able to have babies if you lift that thing. Or, people would say “Oh it’s not appropriate for you to go there as a woman, it’s not appropriate for you to do this as a woman.” It’s like, no one is talking around it, everyone’s just like “This is like, not OK.” Or “Your function is to have children,” and, I’m not saying that that’s not something that is said, or communicated in America, I think that’s communicated in America in about a bazillion different ways. In my experience it is rare to hear it so explicitly. It’s rare for people to say, “You specifically cannot do that because you are a woman.” It’s more like “Oh are you sure of that? Well, I think you can’t do that for this reason or for this reason or for this made up reason” or “Well don’t you know what I mean,” but underneath it people are saying “Cause you’re a woman.”

Gender determines daily expectations of behavior,

Julia: Wherever I went, no matter where I was, no matter what context I was in, the first few questions people would say, I’ll say three questions, “How old are you? Are you married? Why aren’t you married? Like, no one was like playing around with, “Oh where are you coming from?” and “How are you?” People say those things too. But very explicitly wanted to kind of situate me in, “Do you have a husband?” Like “What is wrong if you don’t have a husband?” You know what I mean, like, “What’s amiss here?” And again, these are things that are communicated, I think a bazillion ways in America but not usually so straightforwardly in my experience. And so the sort of veneer level is different. What is underneath, I think is the same. And I won’t say universal but certainly in every place I’ve ever been. Like a highly patriarchal culture, a culture that really maintains a power hierarchy through violence where women are threatened. Sort of like bodily and socially with, with harm if they don’t stay in line. That is so consistent in Russia and the U.S. and so many different places and communities that there’s no difference there. I just have a distinct advantage in Russia of people naming more explicitly what the expectations were and how people ought to behave. Which is great. At least we know the expectations are.

In the workplace,

Julia: Like for example, in Russia or in Kamchatka specifically, in the Russian Far North and Far East, women have shorter workweeks. It’s a federally mandated shorter workweek, because women have, you know, have other responsibilities. First off, they are weaker, so they need accommodations. And second off, because they have a double shift of caring for the home and working. So, that is contemporary Russian accommodation, sort of explicit accommodation of the burden—.

Lisa: OK. I’m just sitting here listening and wishing I had those accommodations in my life. Like I’ve built them now, but there have been times when I’ve had to fight for them. So it’s just interesting.

And the home,

Julia: That’s what’s fascinating. And it’s a real, actually it’s a really interesting transition in Russian cultural thinking because, they, in the beginning of the Soviet Union it was all about sort of like, everyone has to have the same thing. I’m being very general here again. But, like women and men are working the same amount. Everyone is so strong. Everyone’s doing a great job. But then women have this extra burden, and I think you could make an argument for like, “Is there a way to systematically eliminate women’s extra burden? Is there a way to make things more equitable, rather than sort of, penalizing women in the workforce and accommodating their extra work at home? Can we share the extra work at home?” and in the beginning of the Soviet Union they were really into that.

While women’s “Second Shift” continues worldwide.

Julia: They were like “Okay, so everyone’s going to live in communal apartments, and we’re going to have public childcare, and abortions whenever you want, you know abortions on demand, like divorce really easy to access. We’re basically like “We don’t need to sort of saddle you with the burdens of the home or of the family if they’re not working for you.” And that ended up really lowering the birth rate in Russia and the Soviet Union. And so then they were like “Just kidding. Roll those all back. Like women you keep on doing your thing” and then, and it resulted in this really, really incredibly disproportionate double shift for women, of having both work in the workplace, work at home. And so now there’s this accommodation of women’s burden at home. And when I look at that from my super-American perspective, and also from my American perspective as a young childless person, I’m like, “Yes! I would love a shortened workweek, love that,” but also like, “Why isn’t there more cultural emphasis on equity in the household?” But also, I talk that talk, but when it comes to my home and the homes of everyone I know, who is doing the majority of the household care? It’s the woman. So, again, this is something that Russians are naming explicitly. And Americans are sort of, or at least my American communities, talking the talk around equality, but everyone’s doing the same thing. Everyone’s behaving in the same way. Sort of like cultural reinforcing of patriarchy is persistent across the nation.

Communism colonized Indigenous communities,

Lisa: The history of Russian treatment of Indigenous people has similarities and differences with the history of North American treatment of Indigenous people. Given the year that you spent in Kamchatka, the year and a half, can you reflect on some of those similarities and differences both before and after the disintegration of the USSR and how that reflects currently in terms of cultural survival?

Julia: It’s a very interesting thing, the similarities and differences. And I’m speaking again from my understanding as a fiction writer and not as a scholar of Indigenous history across Beringia, for example, or as a scholar of Soviet history. There are so many particularities here. It’s what, like four miles or something from Alaskan territory to Russian territory? There’s so much interchange between different people, different communities, for so long. It’s really, really fascinating to think about how the state has influenced different or similar directions in Russia and the US. My understanding of American history in Alaska or of sort of the American state over North American lands, has been one of attempted, assimilation or extinction, and sometimes of sort of isolation around extinction. You know what I mean like, we are either going to, we’re going to make these people disappear, and the way that we’re going to do that is that, we’re either going to put them in communities that have no infrastructure or funding or support that are away from their lands or we’re going to try to convert them and force them into mainstream capitalists, white American models. Or we’re going to undercut their industry and economy and way of life in order to make ours dominant.As centralization sacrificed culture,

[Lisa: I think just even the notion of having them come together in a community for a school. When you take the migrant culture and you put it in one place, that that by itself has been devastating.

Julia: Yes.]Lisa: How have Indigenous languages survived and are they still nurtured?

Julia: So it’s really interesting that you mentioned schools for example, like schools and settlements as a sort of demolisher of Indigenous ways of life and families and communities. In Soviet Kamchatka, and the Soviet Union in general, there is a lot of, there was a lot of, sort of lip service and celebration of ethnic and racial diversity. That was something that was sort of huge. And I’m talking about the Soviet Union because Kamchatka and Chukotka saw colonization and the destruction that colonization brought from disease, prior to the Soviet Union. And yet the Soviet Union saw such a buildup and such an expansion of ethnic Russian presence in those regions. But it’s a really fascinating sort of century to look at in terms of the effect on Indigenous ways of life. The Soviet Union was very into ostensibly preserving Indigenous culture or ethnicity, I would say more specifically. And I think that’s the place in which it differs from American history. Like the Soviets are very into, for example, creating alphabets for Indigenous languages on Kamchatka, and teaching those languages in schools.

For the good of the State.

But more than they wanted someone to be Even, or they wanted someone to be Koryak, they wanted everyone to be Soviet, and you could be Even and Soviet, but you had to be Soviet first. And that meant a model of centralization around schooling that your kids had to come to, like a settlement to go to school, then they had to.

Reindeer herders resettled into villages

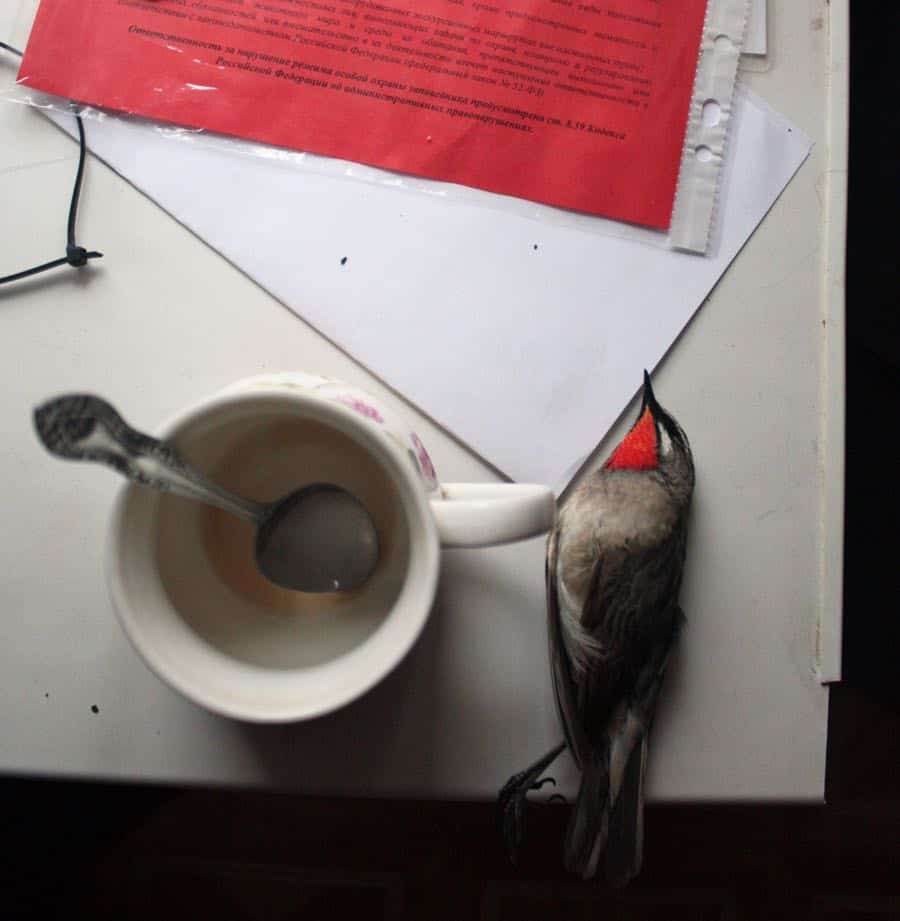

Reindeer herders camp, near Anavgay, Kamchatka, © Julia Phillips, used by permission

Julia: It meant a model of centralization around household life where if you had previously lived for example, with your reindeer herd, or in moving fishing camps that sort of moved up and down with the fish, now they were sort of leveling those villages or, and building on top of them, Soviet apartment blocks and saying like “Look at this. You have a modern home you have it and now you know, we are creating a structure where all of the reindeer herders are going to be collectivized and you have a central committee in which you share profits and through which you get your wages and the state provides, the state provides. And so there was a lot of talk around preservation of reindeer. Reindeer herding got a lot of funding, especially in the 70s and 80s.

For the sake of economic production

Julia: Or, you know, whaling was so important for the Soviet Union up until the 70s and there were a lot of whale processing plants around (this was more on Chukotka, not on Kamchatka). And so Indigenous communities were highly valued and sort of lauded for those services to the state. And yet what sustains their ways of life and their communities was destroyed. This sort of generational connection, passing of knowledge, language, religion, I mean, like it was just demolished in order to support a Soviet national identity. And you see it now in language.

Resulting in loss of Indigenous languages.

Julia: So for example, Even people, of whom there are a few characters in this book, are not Indigenous Kamchatkans they’re Indigenous Siberians, and they came to Kamchatka relatively recently like in the eighteen hundreds, but Koryak people who are in this book they’re from Koryak, like Chander is a Koryak character. Koryak people are Indigenous Kamchatkans and have been on Kamchatka for many many thousands of years, and Itelmen people are also Indigenous Kamchatkans and have been on Kamchatka for thousands of years, and I believe there are now, although I’m saying a statistic that’s a few years old, I think there are now eleven Native Itelmen speakers in the world. It is a language that has been destroyed by the state severing the ties between generations. And people are really working, community activists, Indigenous activists are working in their communities to revive and preserve those languages.Colonialism under any governmental system

Julia: But, it is really shocking, and I guess it’s unsurprising in many ways, to see how effectively the state has killed so many vital parts of what made these communities thrive.

Lisa: Okay. It’s interesting listening to you and thinking about how a governmental structure, whether Soviet or American, has, in the guise of preservation—or not, explicitly or implicitly, broken those connections through a completely different worldview that just doesn’t even begin to fathom the importance of movement and motion to a culture. You know, a hunting-gathering culture versus an agricultural culture, versus an industrial culture. It is so different.

Disrupts cultural continuity.

Lisa: And yeah, like we said at the beginning, this whole notion of “Well we’re going to come to a school,” that, you know, it’s sort of a tool for survival into the next century to have that education, but it is so disruptive to the continuity of the thousands of years of culture on the land.

Julia: Yeah.

Lisa: So, it’s interesting to hear, how Americans will so quickly, at least when I was growing up, set themselves apart from Soviet Russia. But there is that similarity. So I guess that’s what I’m curious about, the differences.

Yet Indigenous Kamchatkans in the post-Soviet era,

Lisa: So now you’re talking about post-Soviet Russia. Do you feel like there’s been an improvement or worsening in the conditions which would nurture the survival of those Indigenous cultures, of land-based survival?

Julia: Kamchatka has a very specific relationship to the memory of the Soviet Union. Kamchatka was extraordinarily well-funded during the 20th century by the Soviet Union. Because it was a military base it had, food it had resources, it had support, when so many other parts of the Soviet Union didn’t. It was a relatively very wealthy region and it had a lot of attention, a lot of prestige and that was true in the city, with for example ethnic Russian folks who were working for the military, and it was also true in Indigenous communities even as these policies were being enacted. There was also a lot of structural support, in terms of how everyone was getting paid–everyone had food, everyone had their industry subsidized, like the state was outlaying a lot of money and effort to ensure that you had a sort of stable and relatively privileged existence on Kamchatka. I say that, also of course acknowledging, as we just said, like there’s so many costs to Soviet policy. But, that stability was enormous.

“Kamchatka has a very specific relationship to the memory of the Soviet Union. Kamchatka was extraordinarily well-funded during the 20th century by the Soviet Union. Because it was a military base it had, food it had resources, it had support, when so many other parts of the Soviet Union didn’t. It was a relatively very wealthy region and it had a lot of attention, a lot of prestige . . . that stability was enormous.”

Also have a sense of loss,

Julia: At this point, I would say everyone I’m talking to remembers the Soviet Union or is a child. If I’m talking to someone who is let’s say, 30 or younger, they have no sort of relationship except for what their parents told them. For folks who have a memory of the Soviet period, and this is the case with ethnic Russians I talked to, and the case with Indigenous folks I talked to over and over again, they say basically, “We’ve got to go back there.” Kamchatka votes much more communist than many other regions do in Russia, it votes relatively strongly communist because that was a time of great support. And just like that character said in that excerpt you read before (see episode 1 block quotes), after the Soviet Union fell, Kamchatka’s funding and support was stripped. I mean like, no food, no heating oil, no nothing, nothing. It is, and so, you know this is where I say generally like I’m speaking in swaths. There are so many people of course who don’t vote communist, who don’t want to return to the Soviet Union who see a different future. But I would say most of the people to whom I spoke, certainly, whether it was in the city or whether it was in the village, especially those in villages—people outside the city have much fewer resources now, and much less infrastructure, and many, many, many of them are saying “We have lost.” You know, “Our subsidies are gone now, reindeer herding, that is not supported anymore. Fishing is now restricted with these anti-poaching things. There’s all this government corruption. All of these. We have left the Golden Age.” I would say that there’s a million exceptions to that rule, you know.

Leaving the ‘Golden Age’

Lisa: In Alaska, we’re coming to the end of our Golden Age of Oil. There’s a level of anxiety right now in the state that’s extremely high, and a level of divisiveness about you know, what’s the best way forward. And so it’s really interesting to me to hear about it. And I was reading that quote earlier about what happened in Palana, and I’m guessing that’s from conversations you had. And I’m reflecting on my own memory of hearing about what was happening in Russia in the late 1990s where these remote communities just didn’t have access to some very basic things. And I was thinking about that, I was thinking you know it might be nice to hear you talk a little bit about what that means in a rural place when government infrastructure fails. I have a sense of that from having been in a village when we didn’t, when that infrastructure failed 20 years ago, or came very close to failing from lack of funding. But I’d be curious to hear you talk a little bit about the stories you heard.

Valley of the Geysers, man. Photo © Julia Phillips, used by permission.

Julia: That’s really that’s–Of course. What you’re feeling emotionally is so sad. I would say at least in my limited circle I had no idea that was going on in Alaska, I’m so sorry. That’s immense. I’m so curious about what your experience was like in that village when infrastructure came close to failing because, because I think firsthand, that lived experience is, has the specificity and a feel for which hearing about it second-hand never reaches. When I think about the stories I heard secondhand in Kamchatka, I think this will be no surprise to you, but it was always a surprise to me, how much closer death is, how much closer, the sort of border between life and death is in Kamchatka, and the everyday than it is in, I think in a city or in a place with more infrastructure. And a lot of the stories of infrastructure failing, or disappearing, or not being maintained in Kamchatka, which is a territory that needs constant maintenance because it is so geothermally active and the climate is so harsh and utilities degrade so quickly. So many of the stories are stories of when there is not enough, when there are no groceries, when there is no heat. When it’s winter and that means there’s minimal fuel and there is no food to be harvested or found or not enough food to be harvested or found. Then people are dying, and people are, eating their dogs, and then die.

Abandoned—with broken promises

And it is an extraordinary betrayal of a national promise to care for, that the state will care for the people and its land. And the state has cared for them in the past, that the state has said “Yes, we are here, you can depend on us. Put aside your traditional ways of gathering food or of looking out for each other. Because we are here now, and we are here to, you know, supplant your economy with our economy now, so you can depend on it and we’ll be there.” And then for that state to disappear, is deadly. It’s really deadly.

Lisa: Thank you. Yeah.

Valley of Geysers, Kamchatka. Photo © Julia Phillips, used by permission

End of “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3”

That concludes the third episode of “An Interview with Julia Phillips.” Please subscribe to our podcast, Salmonberries, to be notified when the next episode, the wrap-up for the interview, is released. In episode 4, Phillips reflects with a sense of humor, on how her time in rural Kamchatka shifted her own worldview, and she gives us a peek forward, to her future writing projects.

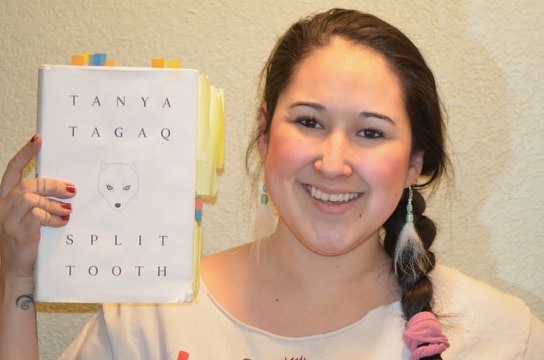

To read podcast transcripts, or our book review of Disappearing Earth, please go to our website at DenaliSunrise.com/blog. Interspersed with transcript postings of the episodes of “An Interview with Julia Phillips,” our website will post reviews of relevant books by authors from the circumpolar North which are relevant to rural Alaska. Recently, this included a review of two books by Canadian Ojibwe journalist Tanya Talaga, titled Seven Fallen Feathers and All Our Relations, both from House of Anansi Press.

Our online bookstore sells many of the books that we discuss, and offers a standard 5% discount. For periodic coupons of up to 20% off of books we review, please sign up for our newsletter at our website, denalisunrise.com. Thank you for listening in to this episode of Salmonberries from Denali Sunrise Publications. [end of transcript]

Julia Phillips, National Book Award Finalist:

Julia Phillips’ book, Disappearing Earth, is now a National Book Award finalist and winners will be announced November 20, 2019. See our review of her book: Women of Kamchatka: Review of Disappearing Earth by Julia Phillips.

Remainder of interview coming soon

If you’d like to be notified when the final post goes up, please sign up for the newsletter to receive notification. Transcript with podcast link will go out as each recording goes live. (Newsletter signup form is at the very bottom of every website page). If you’d like to buy the book and read it first, it’s available at our online store (click on the “buy this book” link in the box below), or buy the book at your local bookstore. For more information about justice issues and resources in Alaska, please check out our page, Resources: Freedom and Security. See also our blog post, “Indigenous Women Authors: Review of The Round House by Louise Erdrich” for more on the topic of representation of Indigenous women in literature.

If you enjoyed listening to An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3, please be sure to listen to the first 2 episodes, and tune in to the fourth and last episode by subscribing to our podcast, Salmonberries (see below for links). Our extensive interview touched on many specific themes that intersect between Kamchatka and Alaska, providing international insight on the rural/urban divide, changing sources of food and energy, murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (#MMIWG), the experience of gender and culture and ethnicity in the north, and of course, books (see below). There will be a total of four episodes.

Podcast download links

This episode is available for download on any of the following linked services (links will be updated when available):

Authors & books, books, books

The following is a list of some of the authors and books mentioned throughout the course of the interview. Links provided to books available through our online bookstore.

Alice Munro

Leo Tolstoy (War and Peace, Anna Karenina

Louise Erdrich (The Round House, Plague of Doves)

Tanya Talaga (Seven Fallen Feathers, All Our Relations)

(For more information on the topic of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) in North America, see our resource page, Freedom and Security, (link there to current newspaper coverage of the two-tiered justice system in Alaska as well as Amnesty International report and Canada report on MMIWG) and read The Round House by Louise Erdrich. Related scholarship has also been done by Canadian Ojibway journalist Tanya Talaga, see her books Seven Fallen Feathers and All Our Relations.)

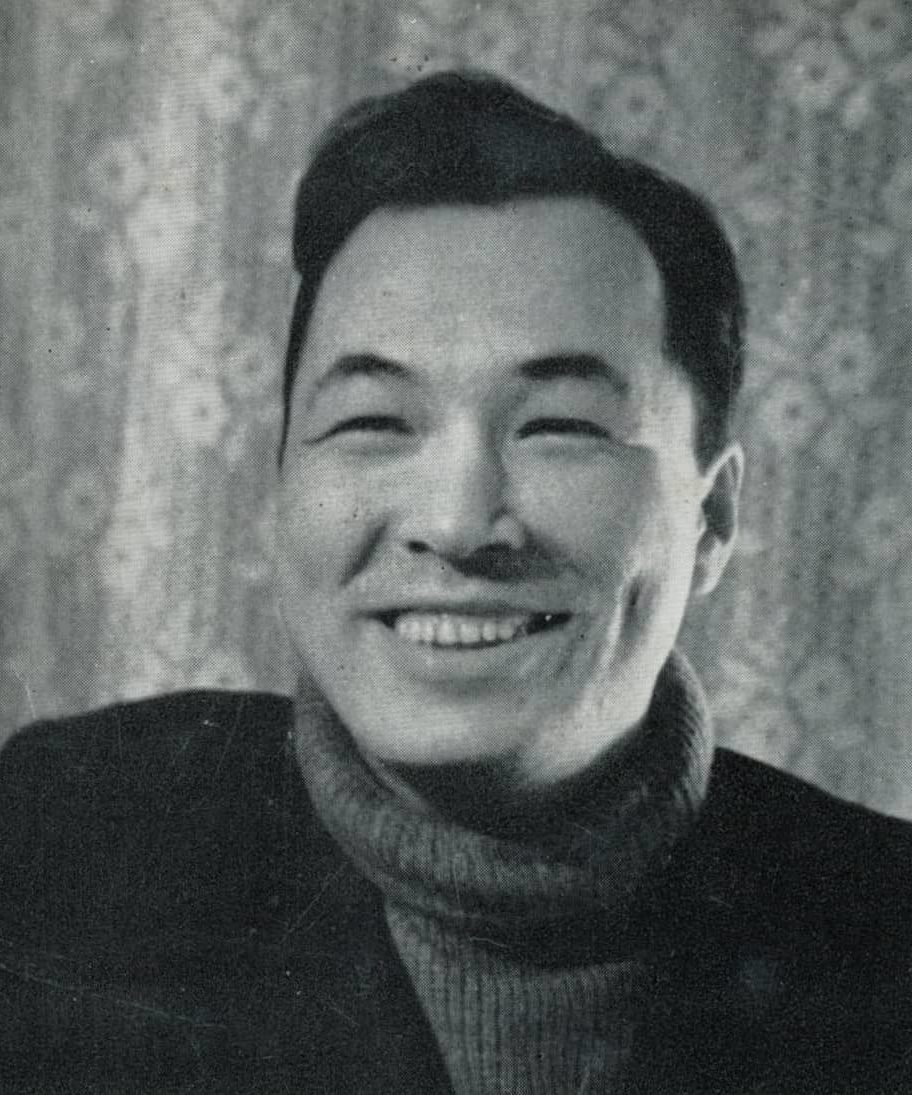

Yuri Rytkheu, a foremost Indigenous Russian author from the Chukchi Peninsula, wrote several books that have been translated into English. A Dream in Polar Fog (translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse) and published by Archipelago Books, translation © 2005, originally published in Russian in 1968. Ryktheu also wrote the Chukchi Bible (also from Archipelago Books, © 2011). Coming this fall from Milkweed Editions is a third book by Ryktheu, translated by Chavasse, titled When Whales Leave.

Floating Coast by Bathsheba Demuth, check out the book review written by Julia Phillips for the New York Times. Published by W.W. Norton & Company, © 2019

Other recently released books mentioned during the interview:

Losing Earth by Nathaniel Rich

Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells

Kamchatka Picnic. © Julia Phillips

Denali Sunrise Publications Bookstore

Click on the button below to purchase this book in our store

(or buy it at your local independent bookstore)

![Kamczadałka [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] Itelmeni 3. Photo used in Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3. Julia Phillips is a national book award finalist for her book Disappearing Earth.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Itelmeni_3.JPG/512px-Itelmeni_3.JPG)

![Johannes Rohr [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] Wooden houses in Esso, Kamchatka, Russia. Photo used in Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3. Julia Phillips is a national book award finalist for her book Disappearing Earth.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Wooden_houses_in_Esso%2C_Kamchatka%2C_Russia.jpg/512px-Wooden_houses_in_Esso%2C_Kamchatka%2C_Russia.jpg)

![Waldemar Jochelson (1855-1937) [Public domain] Koryak woman carrying child. Photo used in An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 3. Julia Phillips is a national book award finalist for her book Disappearing Earth.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a5/Koryak_woman_carrying_child.jpg/256px-Koryak_woman_carrying_child.jpg)