When I first heard about Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern City, by journalist Tanya Talaga, © 2017, House of Anansi Press, I recalled my observations when passing through the township of Armstrong, Ontario, in 1996. An unincorporated area with fewer than 200 residents, three hours north of Thunder Bay, Ontario, Armstrong had several large new homes situated on a rise above the town, each with a law enforcement vehicle parked in the driveway. Below these houses, most of the community lived in older, smaller, rundown homes. I wondered about the relationship between these officers in “Armstrong Heights” and the rest of the community, given the number of law enforcement officers, their geographic location, and clear differential in standard of living.

Understanding racism in the North

Racism: It’s much more pervasive than a set of conscious attitudes and beliefs. Both of Talaga’s recently published books, Seven Fallen Feathers and All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward break down the topics of racism and colonialism in ways that Alaskans will find both relevant and familiar. Read these books to further community conversations about how to address ongoing epidemics of abuse, assault, disappearances, and deaths of Indigenous youth and young adults. Read these books to learn how segregation and discrimination continue to harm Indigenous peoples. Read these books to develop empathy and think about complicity. Read these books to protect and nurture the next generation.

Beyond discrimination

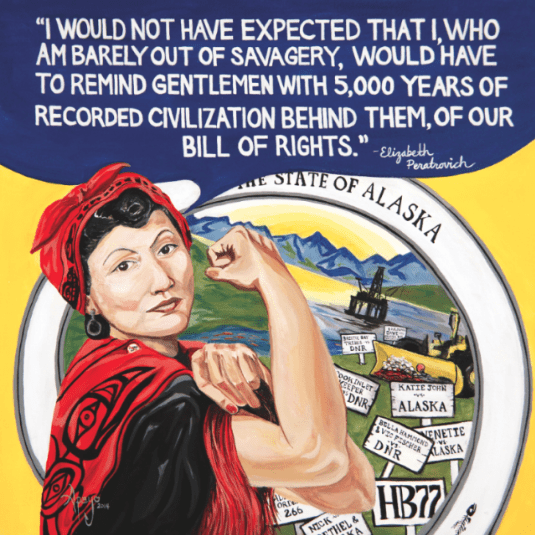

Racism is part of the fabric of daily life for those who endure it, often invisible for those who don’t. The battle to end overt housing and educational discrimination, fought early in Alaska (see our review of Fighter in Velvet Gloves, about Alaskan Civil Rights heroine Elizabeth Peratrovich), is only a first step in dismantling racism.

Building empathy for lost youth

Talaga wrote Seven Fallen Feathers about the families of seven of Ontario’s rural Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) youth who disappeared and died while attending Dennis Franklin Cromarty School in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Talaga, a journalist living in Toronto, with rural Ontario Indigenous and Polish roots, shares candidly her own surprise at just how complex, extensive, and underreported the losses were. Through stories and the use of Ojibwe language, diligent investigative reporting, and interviews, Talaga builds empathy for communities who have lost so many of their youth.

While Nanabijou sleeps

The book opens with a definition of cultural genocide, and takes us in the prologue through the legends of the giant Nanabijou, in which we learn that he fell asleep and the Anishinaabe lost his protection when someone betrayed him. Talaga writes about her struggle to bridge the multiple cultures she comes from, until she understands the significance of the deaths of the seven youth in light of Anishinaabe traditional stories. After introducing the book in this way, she moves into more formal journalistic reporting. The disappearances of the youth in Thunder Bay, we learn, must be understood through both the traditional stories, and the complicated lens of history that includes segregation, lack of cultural awareness from the beginning, coupled with historical and continued inequitable funding and staffing of education and health services for Indigenous children.

Prophecy of the Seven Fires

“Every Anishinaabe person knows the prophecy of the seven fires,” writes Talaga. Each fire refers to a prophecy, a period of time of the history of people. The first three fires refer to the time prior to European contact. The fourth fire refers to the time of the arrival of light-skinned people, and poses two possible outcomes. The fifth fire refers to war and suffering along with the promises, and risks, of Christianity. The sixth fire refers to sickness of spirit and body, and the grief of disconnection between elders and youth. The seventh fire refers to young people rising up to find their own way, with many of the Elders no longer able to help. Success is not a guarantee, but could result in “. . .a rebirth of the Anishinaabe nation. But if they were to fail, all would fail.” We are left to understand that these are the times we live in now.

Segregation originates and persists

The description of segregation in Thunder Bay and rural Ontario is uncomfortably familiar. During the 1990s, I lived about an hour south of Thunder Bay, in rural northeast Minnesota. I would go to this city of over 100,000 people, to shop for groceries. I heard about, and saw firsthand, the division of the city, explained in the prologue of Seven Fallen Feathers: the more affluent Port Arthur, the “white face,” and Fort William, the “red face,” reflect the history of segregation. Most of the Indigenous working class of Thunder Bay still reside in Fort William. A similar pattern of stark segregation endures in other parts of the province.

Racisms kills

Talaga describes the history of overt racism including specific, racially motivated assaults which injured and killed Anishinaabe people living in or near Thunder Bay. She documents in detail the history of residential schools, whose purpose was to disintegrate Indigenous culture through disrupting the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next. She describes again and again, the failure of law enforcement and the health care system, to respond to the plight of the youth at this Thunder Bay residential school. Because of these multiple failures to respond and investigate, families had no closure regarding cause of death. Finally, she analyzes the way pervasive funding inequities set up the tribally run school for failure, leading to this human rights tragedy.

Residential schools disrupt families for generations,

Across North America, survivors of residential schools observed and experienced hunger, disease, sexual and physical abuse, and emotional neglect. Repercussions of this still reverberate. The last federally run Canadian residential school shut down in the 1990s. However, rural community schools remain underfunded and inadequate, many ending at grade 8. The Northern Nishnawbe Education Council started the Dennis Franklin Cromarty Residential School in Thunder Bay to help address the higher education needs of these youth left with the option of ending their education or moving to town. This school faced multiple obstacles from the beginning. Youth from previously traumatized rural communities moved to an urban community to live in other people’s homes who were not close family. Historical prejudices and segregation in the community of Thunder Bay, along with provincial funding inequities, put the school at risk from the beginning. Thus, when students started to disappear, it became evident that the school was inadequately equipped to protect them. Additionally, the lack of connection between the Native community, local law enforcement and medical personnel contributed to delays in communication, investigation, and sharing of information after each disappearance.

And lack of empathy leads to different standards of care.

At least ten Indigenous youth have died since 2000, most of them later found in local rivers. Indigenous search parties, not local law enforcement, led the way in locating the missing. While law enforcement was slow to investigate disappearances, often violating their own policies, they were quick to report that no foul play was suspected, at times even before a coroner report had been issued. Coroner investigations and reports were also delayed in multiple instances, putting their accuracy into question. Ultimately, an inquest into seven of the deaths was granted, but with no fresh leads as to cause of death, there was little closure for the families of the deceased. Multiple protocols were violated and funding inequities and injustices identified. The inquest made 145 recommendations in 2016, which are still in the process of implementation and in some cases subject to annual funding allocation.

Seventh Fire

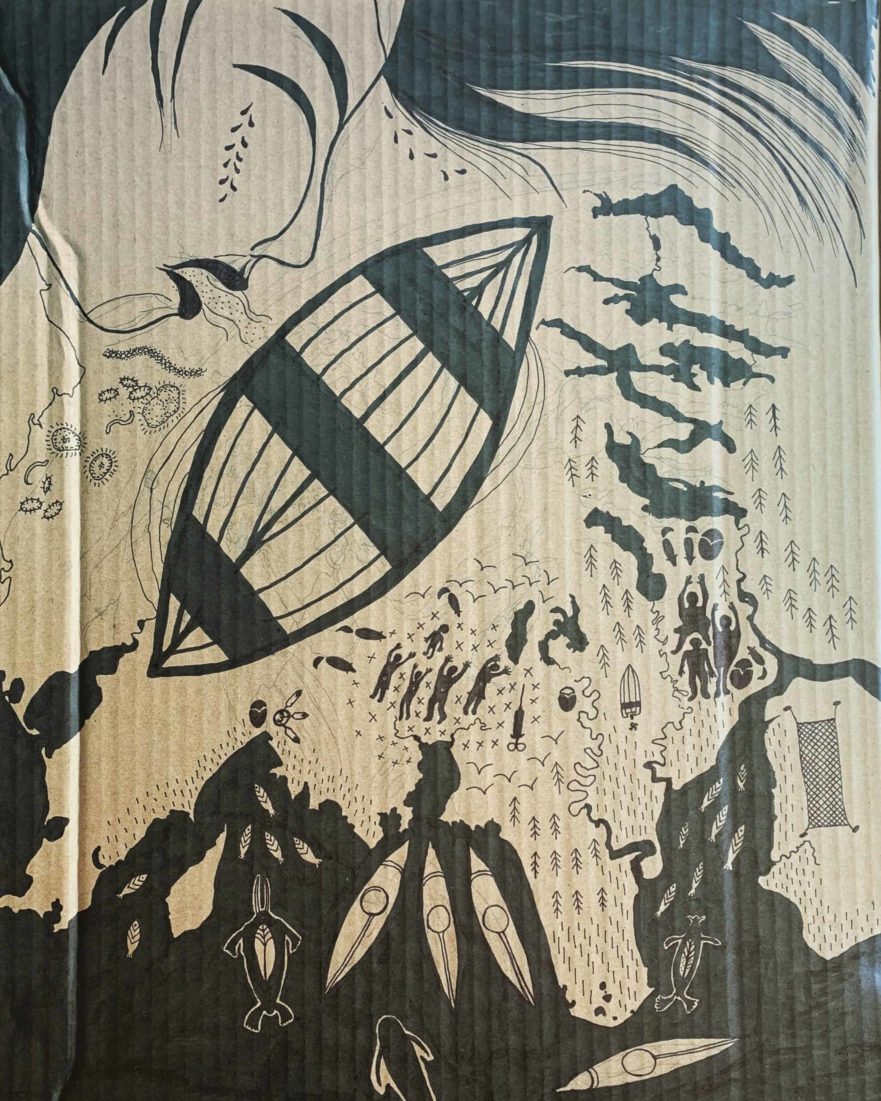

It’s impossible for families and communities to quantify or even fully verbalize the impact of the losses, spiritually, emotionally, economically, of losing their youth. In this context, art becomes a most powerful means of telling a story. One of the affected families includes the Morrisseaus, artists famous throughout Ontario. Christian Morrisseau, the father of one of the youth, painted the artwork used on the book’s cover. A page of his website is dedicated to this book, the artwork on the cover, and his son.

All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward

Expanding on the work of Seven Fallen Feathers, Talaga’s second book, All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward, takes a broader look at the suffering of Indigenous youth and their communities in the form of suicides worldwide, further analyzing root causes. Based on Talaga’s 2017-2018 Atkinson Fellowship in Public Policy, the book comprises the 2018 Massey Lectures, broadcast November 2018 by the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC). By analyzing suicide statistics and researching related struggles in various Indigenous communities around the world, Talaga illuminates the way that cultural genocide has been and continues to be perpetuated through assault on sources of land-based food, traditional means of transportation, and education. From killing bison in the Great Plains, to killing dogs that the Iñuit relied upon, Talaga points out, removing access to traditional economies delivers death quickly–whether intentional, or not.

Truth and Reconciliation is an ongoing process

In Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established in 2008, describes cultural genocide and accepts responsibility for the role of the Canadian government in perpetrating the boarding school tragedy. It lists 94 Calls-to-Action. Earlier this year, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls also names the Canadian cultural genocide and asks whether it has ended. High Country News covered the release of the 1,200 page inquiry in their article ‘This is genocide’: The final report of Canada’s inquiry into MMIWG,’ noting the words of Chief Commissioner Marion Buller, who was quoted as saying “an absolute paradigm shift is required to dismantle colonialism in Canadian society.”

Why this matters in Alaska

Seven Fallen Feathers describes the impact of genocide on Anishinaabe in Canada. Alaska and the United States have yet to reckon with our own history of forced residential schools and its ongoing impacts. We, too, have high rates of murdered and missing Indigenous women. With the recent recall of Judge Corey in the wake of the handling of the “one free pass” Schneider sexual assault case, and the killing of 10-year-old Ashley Barr in Kotzebue, the Alaskan public consciousness has awakened on a broader level about similar concerns around what is happening to Indigenous youth, that have been simmering for a long time. All Our Relations calls attention to another issue little discussed in Alaska, which is that suicide rates among the subpopulation of young Alaska Native men in Alaska are likely among the highest in the world.

Our children, nieces and nephews

This isn’t an abstract issue. It’s about love for our sisters and brothers, nieces and nephews, friends and neighbors. Alaska is a diverse state and the Alaska Native community is inextricably connected to each other statewide, and across all levels of society with the settler families of the past centuries, and more recent immigrants, through marriage, friendships, schools and work. When an Indigenous youth in Alaska dies, it strikes at the core of our hearts. No one I know in Alaska has not been affected by the death of a young Indigenous person. Beyond ending discrimination, understanding the underpinnings of racism and colonialism, are necessary next steps to ending the deaths of Indigenous youth here, just as much as in Canada.

Media coverage: Lawless

Talaga’s journey of discovery underscores the responsibility of journalists to dig deeper to understand the complexities of Indigenous issues in rural areas of the north, often overlooked by larger urban media outlets. In Alaska, the long history of a two-tier law enforcement system between urban and rural areas has come to the attention of the Anchorage Daily News and ProPublica, who have made a yearlong project of analyzing and reporting on the problem of sexual violence in Alaska in their series, “Lawless.” Underscoring the importance of media coverage, within two weeks of their initial article, U.S. Attorney General William Barr came to Alaska, traveled to villages and listened to Alaska Native leaders, and was appalled by the lack of law enforcement in rural Alaska. Within a month, he declared a public safety emergency in rural Alaska, resulting in some immediate and possibly some long-term funding allocations to boost rural law enforcement and related agencies. How this gets administered, whether the state will maintain adequate funding of safety net services, and whether this declaration will result in increased safety for Alaska Native women, remains to be seen.

Art: The Kaspek Project

Art: The Kaspek Project

In Alaska, as in Canada and the lower 48, there is growing awareness of the problem of missing and murdered Indigenous women; Amber Webb has helped increase this awareness through her artwork. She has felt the pang of loss in her community, and transmuted this in ways that bring the pain home to those less familiar. By traveling with the Kaspek Project, she brings a level of emotion that is needed for people to develop empathy. Art reaches people in ways and places that words cannot, elevating action to protect lives.

The way forward in Alaska

Indigenous youth and their families in Alaska, Canada, and worldwide, continue to suffer from epidemic and disproportionate rates of sexual abuse, violence, suicides, disappearances, and health disparities. Beyond discrimination, it’s important to analyze root causes and intergenerational effects of racism and colonialism, and acknowledge the resulting, ongoing cultural genocides. Ultimately, to reduce violent deaths among Alaska and Indigenous communities worldwide, will require restructuring institutions at all levels of society which continue to perpetuate the structural inequities born of racism, inherent in colonialist mentalities. Some agencies working toward these changes are listed on our Freedom and Security resource page. If you know of others that should be listed there, please let me know.