Editor’s Note: This review of Under Nushagak Bluff by Mia C. Heavener, is part one of two posts about pandemics in rural Alaska. Both posts feature creative responses from surviving descendants of the 1918 flu pandemic in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Historical notes about that pandemic appear at the end of this book review. (Part two, a separate post featuring artwork by Amber Webb, will be linked here when it goes live).

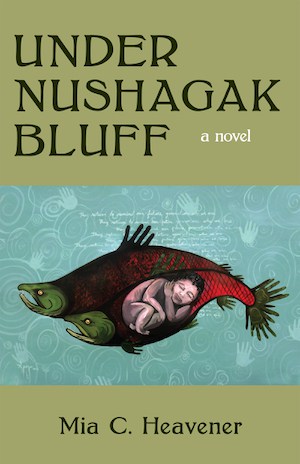

Mia Heavener’s debut novel, published 2019 by Red Hen Press. Cover artwork by Apayuq.

Under Nushagak Bluff

Seagulls swoop and dive, crying in the salty air. The waves of Nushagak Bay crash on sandbars and rocky shores. Machines rattle the warehouses on the cannery side of the village “where the beach flattened and the boardwalks grew tall.”

From an investigation of silence

So many sounds; so many stories. Yet as I page through Mia Heavener’s new novel Under Nushagak Bluff under the long shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is the novel’s subtle and steady investigation of silence that most captivates me.

To an investigation of memory

Under Nushagak Bluff follows the descendants of a character named Marulia, the only one in her bloodline to survive an early 20th century epidemic. Marulia relives the loss every day of her life. Yet she passes only fragments of the experience on to her daughter, Anne Girl.

How pain erodes history

The growing gaps in one family’s story loom as characters navigate more immediate tensions with Nushagak’s missionary and cannery presence. Early in the novel, mother and daughter glance at the fresh, painted siding and clean white steps on their way to check their fishnets: this new order makes Anne Girl feel “as if her qespeq was a sloppy shirt rather than a loose pullover that allowed the salt of the bay to move through her” while Marulia clicks her tongue at the chapel’s steeple “as if it were a large tooth feeding on the villagers.” In the pain of the present, characters avoid speaking of the shadows cast by the past.

Leaving room to repeat

Scandinavian cannery. Alaska State Library, Arthur L. Agren collection, ca. 1906-1932, ASL-P35-057

In late March of 2020, the Anchorage Press published an article by Joe Yelverton, The Raven’s Gift — The Future Our Past Creates: A Conversation with Don Rearden, which pointed out that consciousness of Alaska’s dark history with epidemics is conspicuously absent from our leaders’ statements, updates, and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Yelverton’s assessment, “leaving out Alaska’s [infectious disease] history tends to be the rule, and not the exception.” Yet our state’s remote, Indigenous population has a history of profound loss due to multiple epidemics brought in from outside, which raises questions, as Yelverton says, about how exactly Alaska handles its history.

An aftermath of erosion

Under Nushagak Bluff does not explore historic Alaskan experiences of disease itself. Heavener’s focus lies just to the side of this: she examines an epidemic’s aftermath through the incremental erosion of one family’s knowledge about their own history. Burying the past in layers of earth, Heavener’s novel asks, precisely how does historic understanding erode? Where does the past, personal and collective, get mis-placed, mis-taken, coded, and ultimately concealed? Heavener explores these questions with care and grace, a deep respect for her characters, and an allegiance to the land. Indeed, the book honors on every page a combination of sea, sky, beach, and tundra, along with the returning salmon, the crying gulls, and the ripe berries they bear.

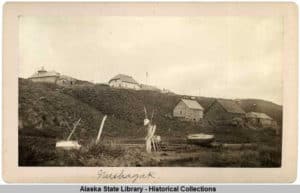

Church and other buildings, Nushagak. Alaska State Library, Samuel J. Call Photograph Collection, ca. 1880-1908, ASL-P181-07

Mud holds secrets of death and life

So it is a particularly fascinating novel to read during the present moment that is saturated with a global pandemic’s fear and suffering, as well as the vigilance, round-the-clock innovation, and far-reaching kindness that emerge in response.

Stories lost in the deep muck of silence

As Nushagak draws its curtains during a WWII blackout order, Anne Girl gives birth to her own daughter, Ellen. By this time, Marulia is already buried and entombed with her memories. From Marulia’s era, there remains only Old Paul. He may be powerful, or just batty; villagers are unsure. Perhaps he would have been a shaman. But by and large, they agree: “Old Paul couldn’t curse or protect you if he wanted to,” writes Heavener. “It was the 1950s. No one had those powers anymore. They disappeared with the big death and the new stories of the missionaries.” Having lost Marulia, Anne Girl will fixate more and more on Old Paul because, Heavener writes, “Anne Girl fiercely believed that Old Paul knew more but had locked all her family’s stories inside his bent body. And she wanted them.”

Heavener unearths stories

Mia C. Heavener is of Norwegian, Polish, and Yup’ik heritage. An engineer by training and profession, she also fishes in Bristol Bay and holds an MFA from Colorado State University. Under Nushagak Bluff, published in November 2019, is Heavener’s first book. And it’s a very exciting addition to the canon of the contemporary Indigenous novel, especially given Heavener’s unusual choice to set the story in historic times.

Under Nushagak Bluff provides historical context for the current pandemic(s)

Indeed, the contemporary Indigenous novel is fundamentally a literature of today. It focuses on characters moving through today’s world—or, in Indigenous speculative fiction, on characters moving through tomorrow’s world—not the world of a hundred years ago, nor even the world of fifty years ago. With few exceptions (though Debra Magpie Earling’s Perma Red stands out as such), the canon primarily asserts active Indigenous presence in contemporary contexts and explores contemporary Indigenous experiences. Heavener’s novel bucks this trend.

Lives of youth depend on learning their history

Alaska State Library, Shattuck, Mrs. Allen (Agnes Swineford), A summer on the Thetis, 1988, ASL-P27-115

By going back in time, Under Nushagak Bluff brings to mind filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk’s Nunavut-based IsumaTV, an artist collective and production company focused on historic reclamation (perhaps best known for producing The Fast Runner trilogy). In interviews, Kunuk says he makes historic cinema because youth’s lives depend on it. He means this literally. Underlying Kunuk’s vision is a consciousness of teen suicide, another epidemic in the North. Kunuk makes historic cinema specifically because youth must have a history in order to imagine a future.

Because silence is also a part of history.

But instead of filling historic gaps with facts and images of western Alaska’s epidemic history, Heavener crafts a subtle and compassionate study of the human moments in which those gaps take shape. Because silence is also part of history.

Dynamic silence

And silence, in Heavener’s hands, is not inert. Silence is dynamic, as we see when Anne Girl is ultimately unable to pass on Marulia’s already fragmented stories. In one scene, Anne Girl begins telling her daughter Ellen about the village’s deadly flood and the frantic scramble to move up the hillside. But Ellen is distracted by a fly on the ridge of her shinbone and Anne Girl stops cold. And so “the story was only partially true,” writes Heavener. “She left out details of the sudden illness, which spread like tundra fire and killed the majority of the villagers before the flood buried their homes.”

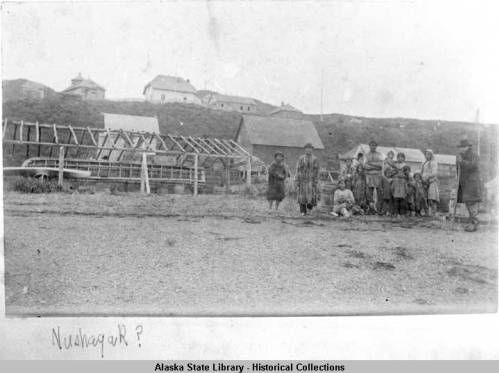

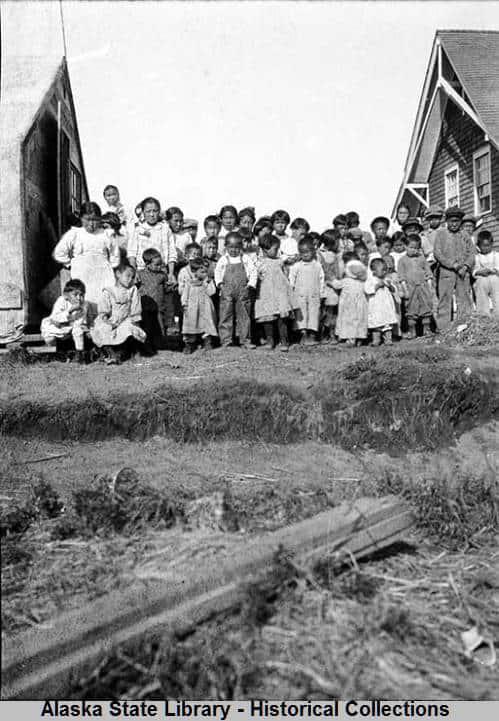

Orphans at Nushagak. Alaska State Library Place File, Alaska Packers Association, ASL-Nushagak-People-4

Loss, silence, rage: What the reader must understand

Though Anne Girl leaves out the sudden illness, it is the epidemic that drives her story’s urgency—an urgency that, stymied, turns hostile:

Anne Girl pulled Ellen’s chin toward her with a bony hand, her fingertips digging into the soft skin. “Listen now. This is your history. And now it’s in that swamp right there. You want that to happen to you?” She heard herself, high and shrill, like a squawking seagull over rotting salmon, both announcing and defending its find. But she wanted Ellen to understand that this was her beginning, where her blood was rooted in the soil.

Of course, child-Ellen doesn’t understand her mother’s anger—nor that her blood is rooted to soil holding the bones of so many lost to disease. But readers do.

Stories become currency

So it is that stories become a currency of their own. So it is that the past grows more riddled with gaps and mysteries, and so it is that these drive the value of stories higher still.

When loss of knowledge is the final terror

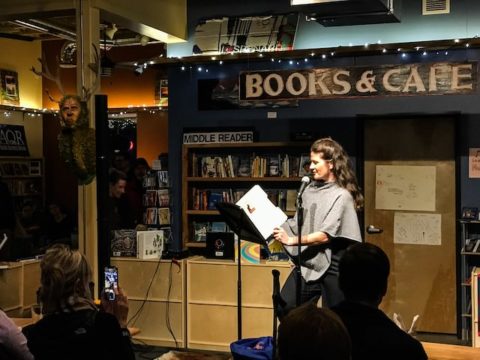

Mia Heavener with fish

As we hunker down to slow the spread of COVID-19, I highly recommend Jill Lepore’s piece on plague literature, What Our Contagion Fables Are Really About, that recently ran in The New Yorker. She writes that “the enemy here is other humans: the touch of other humans, the breath of other humans, and, very often—in the competition for diminishing resources—the mere existence of other humans.” But Lepore finds an interesting turn in modern plague takes. “The final terror” in recent works (like José Saramago’s Blindness) is not illness, bodily decay, and death, but more specifically loss of understanding. Modern plague literature underscores “the preciousness, beauty, and fragility of knowledge.”

And that is precisely where Heavener’s novel comes in.

Editor’s Note:

The 1918 pandemic is the backdrop for Under Nushagak Bluff, but it’s not the only pandemic of concern.

Nushagak Bay map

Around 1918, pandemic influenza claimed the lives of at least 50 million people worldwide, notably killing many young healthy people, within a matter of hours. Parts of remote Alaska may have been harder hit than anywhere else in the world, with a death rate as high 90% in some communities. The grief of widows and widowers, orphans, and the subsequent imposition of reorganized family and community structures, cast a shadow through multiple generations. The book Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World, notes that as many as 40% or more of Alaska Native people from the Bristol Bay region of Southwest Alaska died in the 1918 flu. In some villages, nearly all the adults died within a brief period of time. The Alaska Packers Association’s Report on 1919 Influenza Epidemic for Naknek, Nushagak, and Kvichak Stations, notes they helped care for the ill and the orphans of the region. Most of the Alaska Native residents of Dillingham today descend from those orphans. Under Nushagak Bluff emerges from this silent backdrop of loss. Over 80% of those who died of the influenza epidemic in 1918 were Alaska Native. In 2018, the State of Alaska analyzed the flu data from 1918, noting that a translated death rate in contemporary terms would have been equivalent to nearly 12,000 Alaskans (9600 Alaska Natives).

COVID-19 is the most recent pandemic

While COVID-19 does not yet appear to approach that scale of lethality, it is a new virus and rapidly evolving. It is this history of loss from the 1918 flu, and multiple waves of other epidemics with their ensuing silences, which cast a haunting shadow across rural Alaskans. These shadows motivate rural Alaskans to actively protect their communities from lethal pandemics, viral or otherwise.

While shadows cast from 1918 remain more lethal

At the same time, COVID-19 is only one among many pandemics in rural Alaska, past and present. See the book Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being by Harold Napoleon (of Hooper Bay in Western Alaska) for a direct discussion of the devastating multi-generational repercussions of the pandemic flu on communities that were especially hard-hit. And know that, while COVID-19’s exponential growth means its risks to rural Alaska will continue to grow, several other pandemics, including that of domestic violence and suicide, remain more lethal to rural Alaskans at this time.

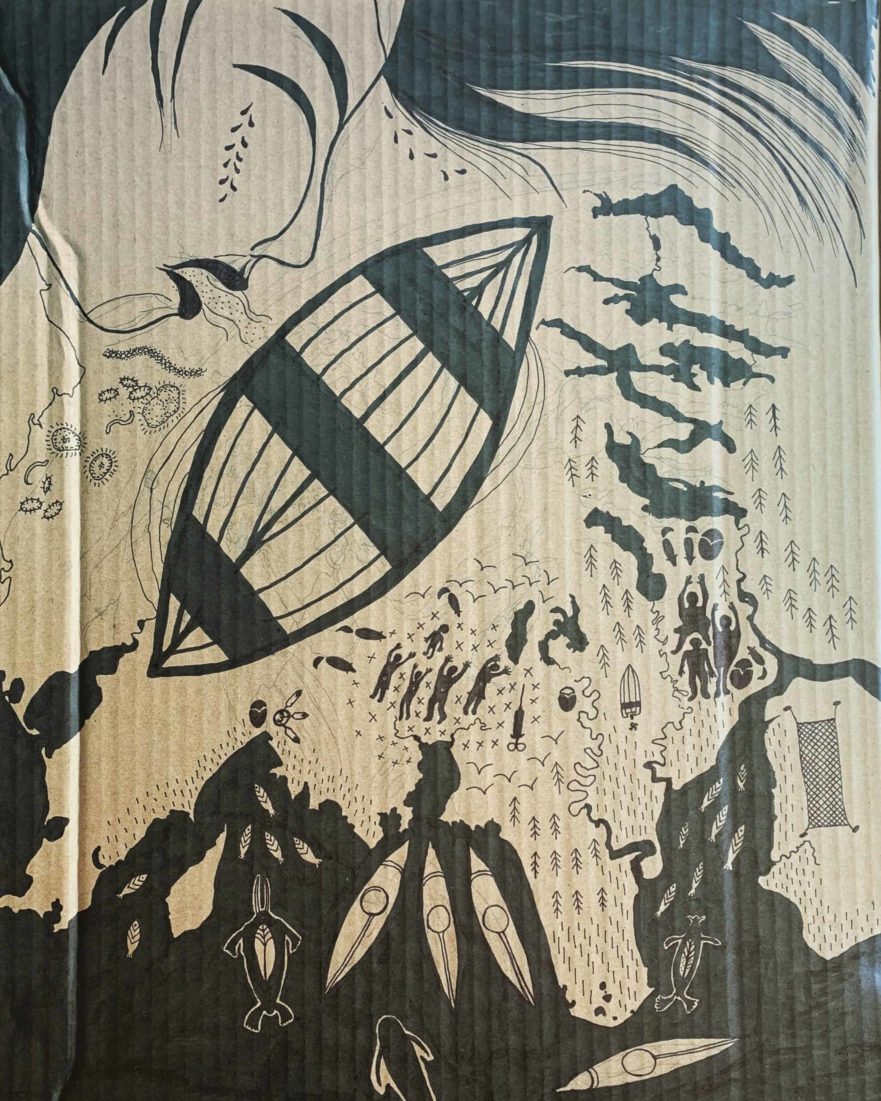

Survival through stories and art

Alaska Native people are incredibly resilient, and the stories of Bristol Bay are being passed on in multiple formats. Part two of this series on pandemics in rural Alaska features artwork by Amber Webb, also of Dillingham, addressing survival of past and current pandemics. One of her works is featured at the bottom of this post.

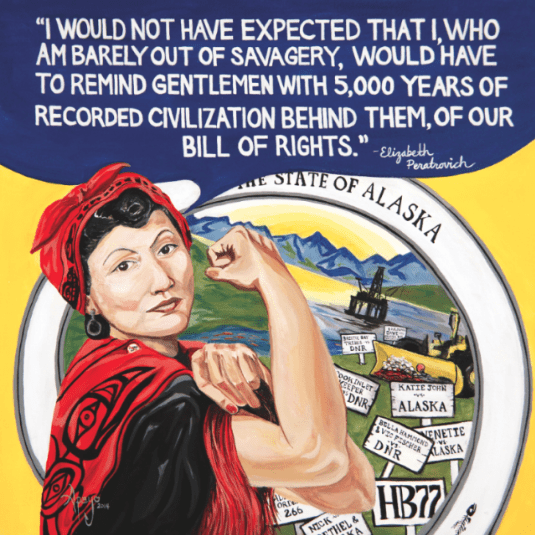

Additionally, the artwork on the cover of Under Nushagak Bluff book is by Apayuq, also of Bristol Bay (her art also appears on the cover of Fighter in Velvet Gloves, and her colorful murals grace buildings in Dillingham and around Alaska).

For more stories about how the people of the far northwest of Alaska responded to the 1918 flu pandemic, also see our review of Menadelook.

Additional notes

An earlier version of the above book review was published by Anchorage Press, “Just to the Side: Reflections on a New Native Novel and Alaska’s Epidemic History.”

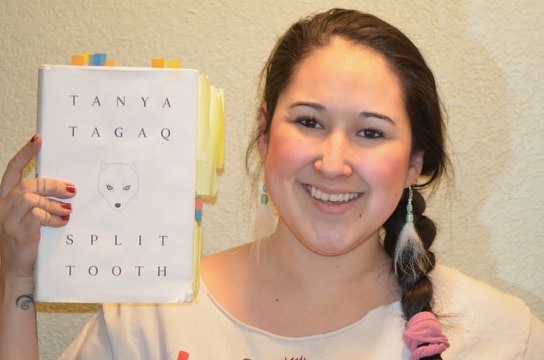

Author Mia C. Heavener

Author Mia Heavener reading from her book, Under Nushagak Bluff. Photo by Jeremy Pataky.

Mia Heavener is of Norwegian, Polish, and Yup’ik heritage. Her experience in rural Alaska is both personal and professional. After graduating from MIT with a degree in civil engineering, Mia returned home to design water and wastewater systems in Alaskan Native villages. During the summers, she commercial fishes with her family in Bristol Bay. She believes that everyone should have a good whiff of the tundra at least once in their life, if not twice. She has an MFA from Colorado State University. Her fiction has appeared in Cortland Review and Willow Springs.

Author of book review, Corinna Cook, PhD

Book review author, Corinna Cook

Book reviewer Corinna Cook is the author of Leavetakings, a lyric essay collection coming out with University of Alaska Press in November 2020. She holds a PhD in English from the University of Missouri and specializes in creative writing theory/history/craft, contemporary Indigenous literature, and circumpolar Indigenous cinema. She writes across literary and academic modes to explore cross-cultural questions. Her creative work appears in Flyway, Ocean State Review, Alaska Magazine, Edible Alaska, and elsewhere; her freelancing appears in 49 Writers and the Rasmuson Foundation’s Artists of Alaska series and in Yukon North of Ordinary; and her critical articles appear in Assay and in New Writing. Supported by a 2018-19 Fulbright Fellowship, a 2018 Alaska Literary Award, and a 2020 Individual Artist Rasmuson Award, Corinna’s current book project explores Alaska-Yukon art, ecology, and colonial history. More at corinnacook.com.

Buy this book

If you would like to purchase this book, ask for it at your favorite independent bookstore, or click on the buy button to go to the detail page for this book at the Denali Sunrise Publications bookstore, which sells quality books relevant to rural Alaska online at a 5% discount off retail, including many of the titles featured on our blog.

For coupon codes offering greater book discounts, please subscribe to our newsletter.

Artwork by Amber Webb

Amber is an Alaskan artist from the Bristol Bay region who lives, works, and creates in Dillingham. She is renown for her work on murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls and the Kuspuk Project. She has created a number of pieces of art related to pandemics in Alaska, and one of those is featured above. See the second post in this blog series to view more of her work.

“Sketching the story of how the Spanish Flu pandemic hit Bristol Bay in 1919 and changed the region. The map is about Goodnews Bay to the edge of Nushagak Bay. It also includes the lakes. Not a very accurate map, but it’s symbolic. They say that people from Kulukak relocated to Kanakanak, Togiak, Manokotak and Aleknagik because so many people died. I know one of my great-grandmothers was from Kulukak, but moved to Kanakanak. I don’t know if it was during this pandemic. We are resilient people.”