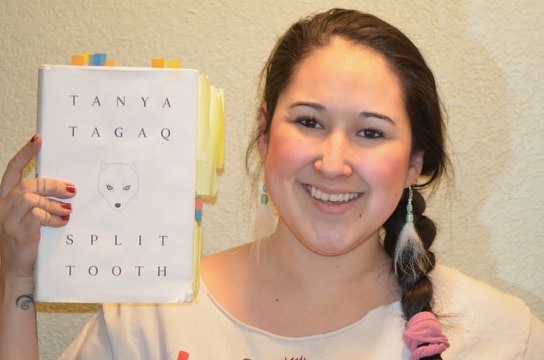

Split Tooth review, written by Iñupiaq author and publisher, M. Jacqui Lambert, who is from Kotzebue, Alaska, with family roots in Noorvik and Kiana.

Split Tooth © 2018, by Tanya Tagaq, Published by Viking Canada of Penguin Random House Canada, September 25, 2018; Audiobook narrated by the author. It was longlisted for the 2018 Scotiabank Giller Prize. This Split Tooth review is of both the print and audio editions of this book.

Author Tanya Tagaq is an acclaimed Inuk “vocalist, throat singer, composer, visual artist, advocate, writer and public speaker from Cambridge Bay, (Iqaluktuutiaq), Nunavut, Canada.” This is Tagaq’s first book.

Nunavut, situated east of Northwest Territories, and northwest of Hudson Bay, forms most of the Canadian archipelago and borders Greenland.

Parallels Between Northwest Alaska and Eastern Canada

A thousand stories woven into one, Tanya Tagaq expresses the expansion of our ancestry — our heritage of the land and the trauma — through beautiful poetry. She narrates a story that we can barely say out loud as Iñuit — not because we’re not allowed to and no one will listen, but because it can be so scary to our inner selves. And that’s what makes the book so real and so valuable. You experience it all on your own. Tagaq puts into words the fear, the confusion, the love and the beauty that all coexist with each other in the Arctic.

Split Tooth Review: Multimedia Storytelling through Print, Audio, Throat-singing, and Art

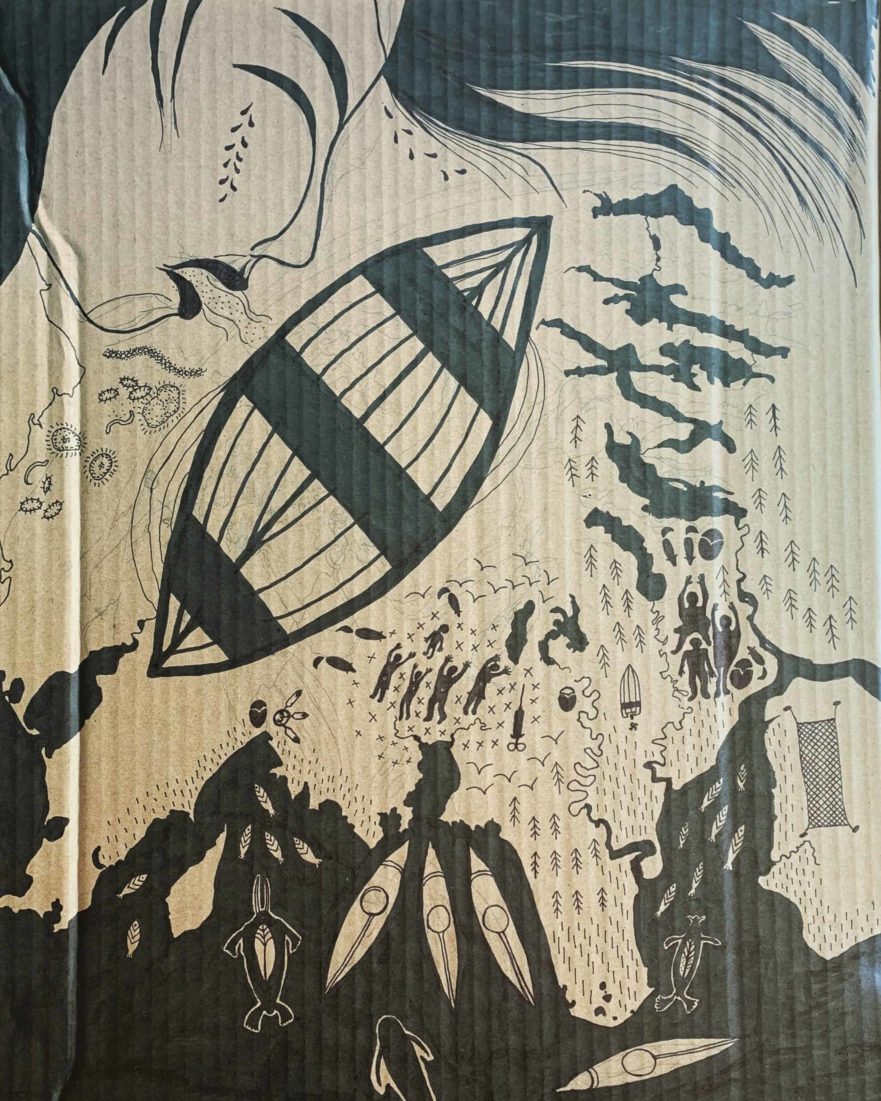

In the print version, Tagaq amplifies the story through both poetry and illustrations of life in the Arctic between the chapters. She adds to the artwork of the printed story, by throat singing in the audiobook. Traditional Iñuit throat songs mimic the sounds of the environment; this extends the story she reads out loud to us. Tagaq uses a variety of voice tones throughout the story to bring it to life. Hearing her different impressions of the characters enhanced the reality of the story, but this style of truth telling can be triggering. I would suggest reading and listening with caution as well as allowing space between sessions to allow internal processing. Split Tooth can serve as a great resource to review and push forward the conversations about the intergenerational trauma that Iñuit have faced since contact of colonization. This book confronted the conversion between spiritual belief systems and often compared Christianity with the traditional perspective of faith in the Arctic environment. It also brought up familiar social issues of alcoholism, sexual assault and the immorality of suicide, all of which are widely known to be increasing over the past several generations.

Stories Between the Traditional and the Contemporary: Circumpolar Truth

It’s hard in the beginning to make sense of what exactly the story is about, but Tagaq still accomplishes putting together the many stories we’ve lived over several decades and several thousand miles of land. I didn’t know that it was possible to relate this much to a woman who grew up 1,400 miles away from me, and two decades before I was born. Split Tooth is the first book to hit this close to home. As an Iñupiaq woman from the Northwest Arctic of Alaska, I’ve traveled between communities in Russia, Canada and Greenland multiple times. My experiences within these places opened my eyes and heart to the expansiveness of who we are as Iñuit. For over a decade, my awareness of our similarities and solidarities has grown. Still, my cultural understanding of Iñuit deepened while reading the smaller details of the two worlds within the Arctic, where the traditional one merges with the contemporary one.

Namelessness

Most of the characters are nameless, which makes me wonder if it’s for the safety of the storyteller or the sanity of the reader. Even though she was generalizing each character, I imagined the real names that I could associate the stories with. Without any names throughout most of the book, I began to piece it together with the names of my own experiences. However, it did seem odd to read the book when I considered the value we put into the names of Iñuit. Our naming process is intentional and our faith is within the spirit Iñuit carry on through the names given to us. Traditionally, a new born child reclaims the name of someone who had recently passed away. Often times, especially when it’s within the family’s lineage, the namesake will naturally carry themselves as if the spirit had never left.

I think the intent in hiding the names could come from multiple reasons. First, it can be an act of paying respect to the cultural value of the names people carry in both languages. Then, it could serve as a true function of the reality within the story where the narrator prefers to play it safe, rather than naming her uncle, a parent’s friend or another man within the small community. It also could be an artistic decision to allow the flexibility for relation to readers across the Arctic.

Dark Confusion . . . Dark Spirits . . .

The main girl is a teenager describing to us what her life is like. She takes us through her home and daily life. She explains the nature to see and the animals to interact with. She tells about different friends and family members, as well as the different kinds of relationships they bring into her life. Then, she walks us through her first spiritual experience of realizing there’s another world beyond us but still around us. This girl, who can play with the spirit world and come back to the real one, clearly experienced sexual trauma. She describes that dark confusion for us. Then, she reveals the dark spirits to us. Her home is the kind where adults go to drink alcohol. It’s a place she doesn’t consider safe. After a few scenes of detailing the moments of her body being invaded, she eventually describes the act of voluntarily leaving her flesh to go into the spirit world which leads to being impregnated by the northern lights.

Dissociation.

That’s when it occurred to me that the other spiritual experiences could describe her tendency to dissociate. Dissociation is a spectrum ranging from daydreaming and spacing out to developing an entirely new identity in order to leave your reality. It’s a coping method that is common among survivors of childhood abuse. Not only would specific sexually traumatic experiences explain the character’s unstable thought process, but so would her stressful home environment that is full of consistently drunk adults who threaten her safety on a daily basis.

That’s when it occurred to me that the other spiritual experiences could describe her tendency to dissociate. Dissociation is a spectrum ranging from daydreaming and spacing out to developing an entirely new identity in order to leave your reality. It’s a coping method that is common among survivors of childhood abuse. Not only would specific sexually traumatic experiences explain the character’s unstable thought process, but so would her stressful home environment that is full of consistently drunk adults who threaten her safety on a daily basis.

As a survivor of sexual assault, it made sense to me that eventually the character found it easier to leave her body and develop a mental function of losing touch with reality. She did not feel safe in her own flesh, so she took us through her messy mind where we hear about the spiritual realm. Maybe it was her abuser that got her pregnant but in her mind, she wanted to believe it was something much bigger than him and that’s the story she wanted to share with us.

Lessons Between the Author and the Audience

With her first pregnancy, the character weaves together this confusion and fear to wrap it in the love of her unborn twins, a boy and a girl. She finally reveals beauty through the process of transitioning into motherhood. Tagaq evokes emotion out of this part of the story through her descriptions of a mother’s love. The excitement climaxes throughout her pregnancy and into the labor it took to give birth to these children, who are the main characters to receive Iñuit names. As she describes the spirit of Savik and Naja, I began to think again of the children I knew while growing up in the Arctic of rural Alaska.

“She gives with abandon and Savik is very protective of her, as if he sees her healing as a waste of energy, energy that could be directed towards him. Energy she could be using to build a shield to protect herself from those that would take too much. He is greedy for her. She generates healing and then feeds from the happiness. In return, Savik filters pain for her. I hope that she does not break once she knows its barbs. Shielded from agony, she grows and feeds the moon. Feasting on frustration, he tunnels into the sun.”

Circumpolar Stories of Moon and Sun

Tagaq’s writing about them triggered a memory of hearing an old Iñuit story I’ve heard before. It explained how the moon is a possessive boy and the sun is his sister who is always chased away by her brother and his aggression. This is just one example of how Tagaq magically weaves in our traditional belief system through contemporary storytelling.

Similar to the most recurring theme of our traditional Iñuit stories, Tagaq uses her fictional writing to instill the thrill of fear within us. She brings up the controversy of Christianity overpowering our land and our faith within it since contact. She talks about the sin of suicide and the vulnerability alcoholics have with evil spirits.

Similar to the most recurring theme of our traditional Iñuit stories, Tagaq uses her fictional writing to instill the thrill of fear within us. She brings up the controversy of Christianity overpowering our land and our faith within it since contact. She talks about the sin of suicide and the vulnerability alcoholics have with evil spirits.

In true Iñuit nature, she forces the end of the book and finishes with an unexpected plot twist, leaving us to decide for ourselves what the lesson was.

Book author Tanya Tagaq tweets @tagaq, and has a website describing her work at tanyatagaq.com.

You can purchase the book at our online bookstore here. In September of 2019 a paperback will also be available.

Split Tooth Review author M. Jacqui Lambert is Publisher of The Qargizine, a quarterly print and digital magazine that celebrates rural and Alaska Native cultures through photos, artwork and stories submitted by people across the state. The next issue is scheduled for release on March 21st, 2019. Lambert is Iñupiaq, from Kotzebue, with family roots in Noorvik and Kiana.

Other reviews on our site of books by circumpolar Iñuit authors:

Alaska Native Anthropology: Review of Menadelook, edited by Eileen Norbert (Menadelook: An Inupiat Teacher’s Photographs of Alaska Village Life, 1907-1932)

Ice, Fire, Survival in Rural Alaska: Review of Wakolee’s Starting a Fire (Starting a Fire: Bringing light to the dark by Tia Wakolee)

See other links related to the circumpolar north at this page: Resources: Our Northern Neighbors.