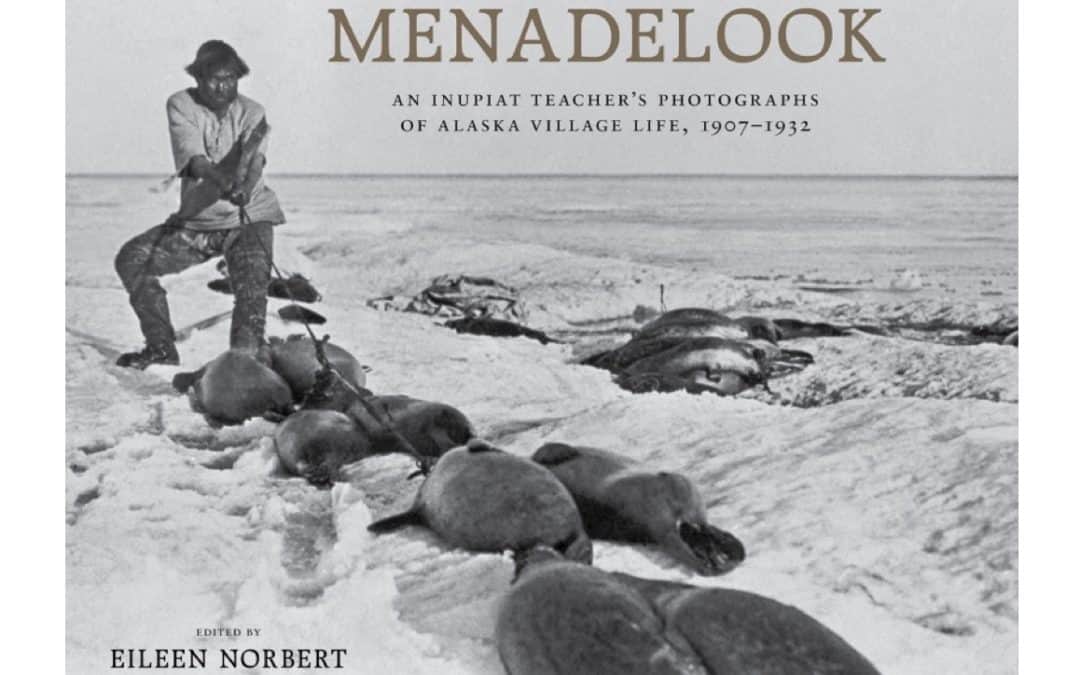

Menadelook: An Inupiat Teacher’s Photographs of Alaska Village Life, 1907-1932, Edited by Eileen Norbert.

©Sealaska Heritage Institute. Published by University of Washington Press, 2017.

Grandaughter of Menadelook Documents His Legacy

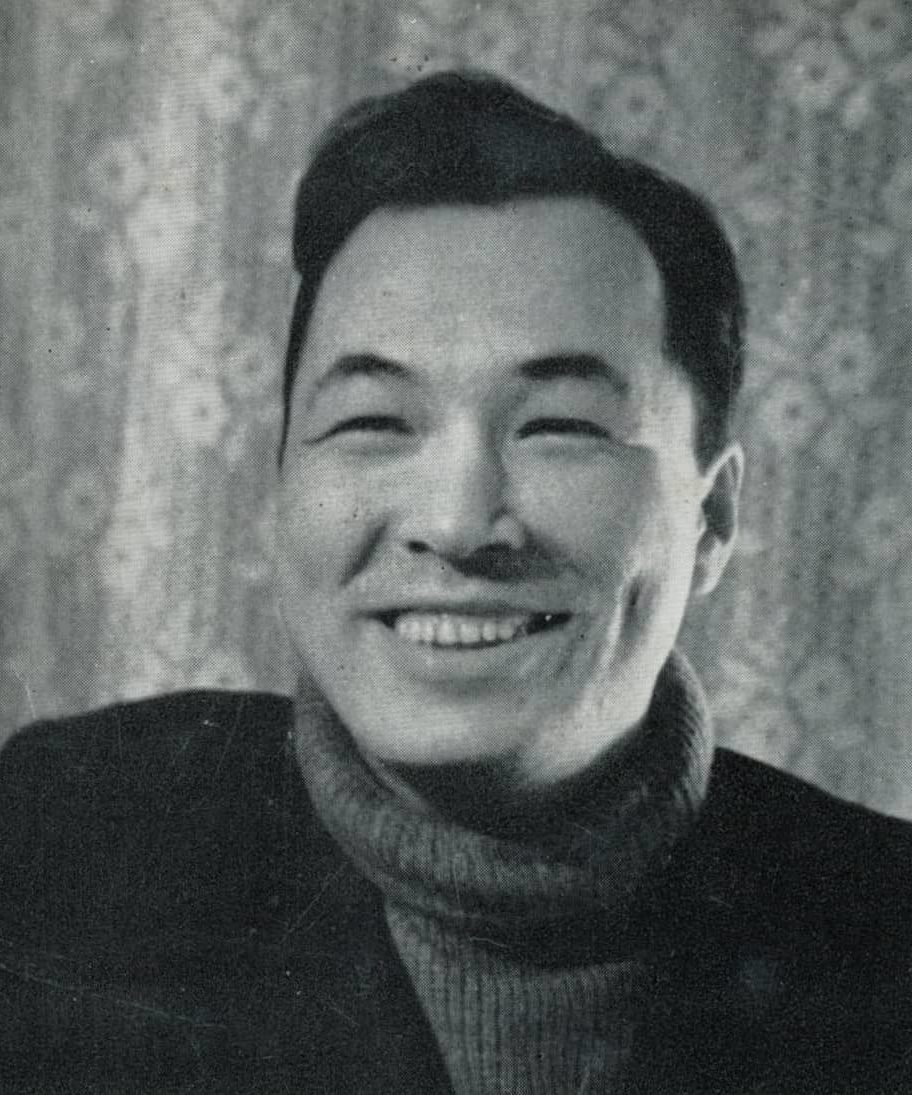

Eileen Norbert has raised the bar for documenting history and culture. Born in the northwestern Alaskan town of Wales in the late 1800s, her grandfather Charles Menadelook developed a passion for photography as a teen and later became one of the first Alaska Native classroom teachers. He traveled with his family to multiple communities in Northwest Alaska to teach in the early 1900s, documenting the integration of new materials and technology into Inupiat daily life, including subsistence traditions. Norbert began collecting and researching her grandfather’s photos and the stories behind them as an anthropology student, “. . . determined to demonstrate that a member of an indigenous society can provide significant information and understanding of one’s own culture and history.” (from the foreword by Rosita Worl). In this, she has succeeded.

Indigenous ways of knowing

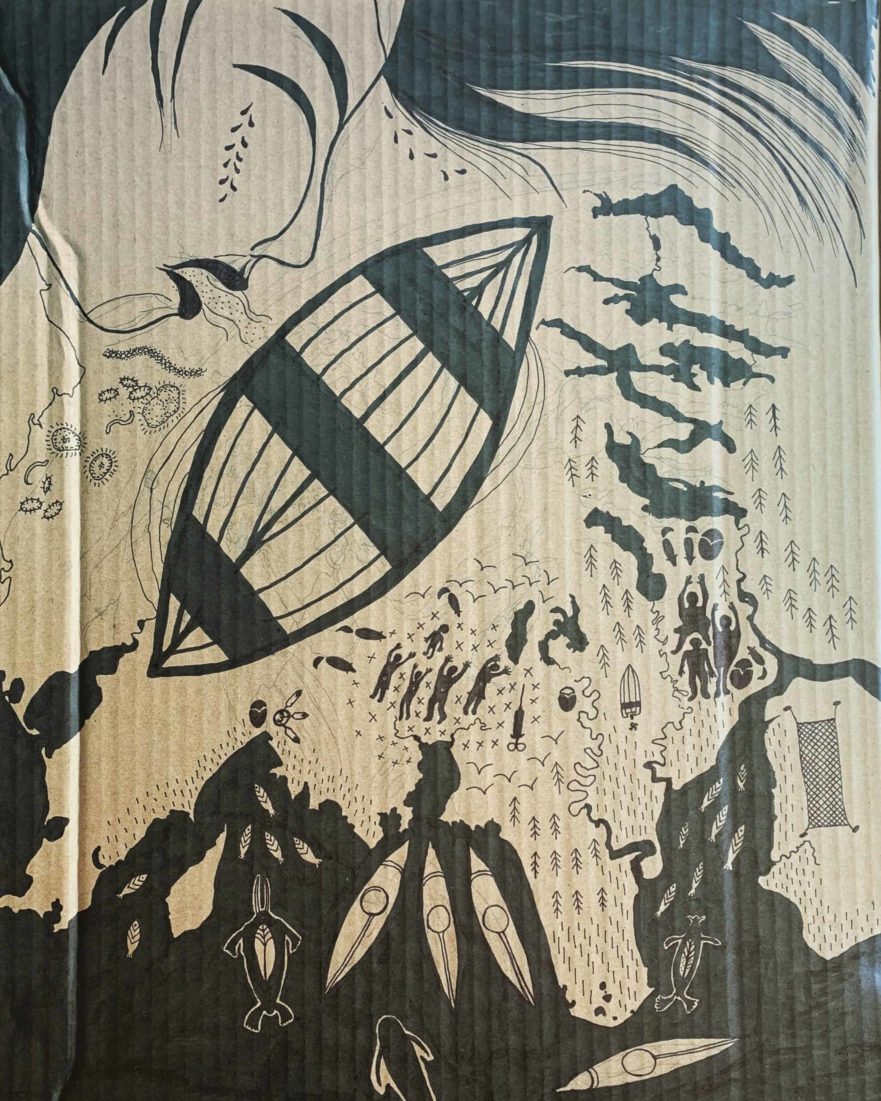

I met Norbert at her booth at the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) convention in Anchorage in October of 2017, and took some time looking at the book before purchasing it. The book’s frontispiece on page 7 compelled me to complete the purchase: A map of Northwestern Alaska, hand-drawn in 1898, by Joe Kakaryook of the Port Clarence area, precedes a contemporary map. The ability to mentally map a large area of land based on lived experience, knowing the land through a combination of stories and by extensive travel in non-motorized watercraft is a skill that amazes and humbles me whenever I am quick enough to recognize it. Deeper in the book on page 25, I am reminded of the dangers involved in acquiring such knowledge as she writes, “Elders told true stories of lost hunters carried away on ice floes and how they survived. Hunters were carried all the way to Point Hope, King Island, and Saint Lawrence Island and managed to make it back home.”

Menadelook established his point of view by taking pictures. . .

Menadelook took pictures of everyday life documenting activities and clothing that held meaning for him, valuing both ancient and modern styles. He took self-portraits while wearing either traditional arctic clothing or 3-piece suits. Menadelook understood that his culture was experiencing rapid change, and appeared at ease with the transition. In every community he served, he contributed to the community with his inherited hunting and gathering skills right along with his modern photography, finance, and teaching skills.

Fashion is a marker for changing traditions, and because his granddaughter understands these changes from within the culture, she is able to help the reader understand as well. On page 88, for a photo of students in the 1920s with aprons on, Norbert points out to the reader the variety of hairstyles as well as footwear, observing that this variety in fashion served as a marker of a culture in transition.

Fashion is a marker for changing traditions, and because his granddaughter understands these changes from within the culture, she is able to help the reader understand as well. On page 88, for a photo of students in the 1920s with aprons on, Norbert points out to the reader the variety of hairstyles as well as footwear, observing that this variety in fashion served as a marker of a culture in transition.

On page 29, Norbert points this out again as she describes the image of a woman with a lard bucket to hold her fishing gear, “Even though  she is using rubber boots instead of waterproof mukluks, she is still wearing warm reindeer socks.” This isn’t just about fashion; Norbert understands the traditional, time-intensive skills required to make the sealskin mukluks that have allowed the Inupiat to survive in the Arctic. Rubber boots may not be a significant improvement so much as a timesaver. But it’s hard to imagine wool socks being warmer than fur.

she is using rubber boots instead of waterproof mukluks, she is still wearing warm reindeer socks.” This isn’t just about fashion; Norbert understands the traditional, time-intensive skills required to make the sealskin mukluks that have allowed the Inupiat to survive in the Arctic. Rubber boots may not be a significant improvement so much as a timesaver. But it’s hard to imagine wool socks being warmer than fur.

On p. 91 another photo from the 1920s shows a woman demonstrating traditional ice fishing during a winter festival, wearing snow goggles to prevent snowblindness, noting that the beautiful parka was not customarily worn while fishing. She has a leg tucked up and is balanced on one foot, while holding the baleen mesh ice scoop pole.

On p. 91 another photo from the 1920s shows a woman demonstrating traditional ice fishing during a winter festival, wearing snow goggles to prevent snowblindness, noting that the beautiful parka was not customarily worn while fishing. She has a leg tucked up and is balanced on one foot, while holding the baleen mesh ice scoop pole.

. . . So the next generation could understand.

To an outside observer with no history in the area, it might be difficult to appreciate the photo on page 82, taken in 1921 in Shishmaref, in which a number of people are cutting sod for a new iglu and, as noted by Norbert, enjoying the activity.

The fact that she observes and comments on their enjoyment gives me just enough pause as someone who has lived in rural Alaska, to think through not only why they might be enjoying this particular task, but why she might also notice and comment on it. There’s a narrow window of time in which the permafrost melts just enough to take up a layer without getting  completely devoured by insects, or ending up knee deep in mud, and from the looks of this photo, the community is working together quickly during that spring window. Her nuanced captions contribute insight that an outside observer might completely miss in sorting through these historic photographs; Eileen’s photo selections throughout this volume underscore the importance of her intersecting roles as both a member of the culture and anthropologist.

completely devoured by insects, or ending up knee deep in mud, and from the looks of this photo, the community is working together quickly during that spring window. Her nuanced captions contribute insight that an outside observer might completely miss in sorting through these historic photographs; Eileen’s photo selections throughout this volume underscore the importance of her intersecting roles as both a member of the culture and anthropologist.

The power of point of view and history is especially reflected on pp. 107-159, where the photos are consolidated for purposes of showing the images before and after restoration work. These photos show expanses of sky and ice and rock and ocean; they show humans with animals in the context of their relationships with the Inuit—dogs pulling a sled, reindeer herding up in the background, walruses dead and in the boat. The harvest, and materials, used to survive are depicted in active, integrated use: Multiple photos depict the walrus hunt and splitting of those hides; other photos show the hides in use, attached to boat frames or used as roofs.

Culture in transition: Menadelook built bridges

Subsistence activities still took priority for Menadelook’s students and he understood that the boys took longer to finish school due to missing class time for hunting activities. This occurred in most of the communities where he worked. “Most of the students in grade 5-8  were between the ages of 14-19. The older students did not attend school for the full year. At the beginning of May, school had to be closed while families trapped and hunted . . .” (p.89) Images of the harvest show up throughout the book, such as the image on p. 79 of a boat loaded with herring, or p. 58 of birds caught with a long-handled net, or p. 59 piles of murre eggs.

were between the ages of 14-19. The older students did not attend school for the full year. At the beginning of May, school had to be closed while families trapped and hunted . . .” (p.89) Images of the harvest show up throughout the book, such as the image on p. 79 of a boat loaded with herring, or p. 58 of birds caught with a long-handled net, or p. 59 piles of murre eggs.

Several photos capture interactions with Siberians who were close neighbors and kin as the international boundary passed between Little Diomede and Diomede; active trade relationships persisted into Menadelook’s time and beyond; this book, and other articles by Norbert elsewhere, illustrate the fluidity of interactions between Inupiat on both sides of the international border and how political changes impacted travel, relationships, and the health of visitors.

Menadelook observed how the flu impacted northwest Alaskans, including his family

The 1918 flu hit Alaska especially hard, and although Menadelook and his immediate family escaped it, his extended family did not. One photo notes Menadelook’s caption indicating the mail carrier brought the sickness to Wales where his extended family had lived until the flu halved the population there, taking both his mother and stepfather. An epidemic of that magnitude brings out extreme responses, and the village of Shishmaref reportedly prevented the flu from moving farther north by effectively prohibiting travel into or out of their village. This definitive action likely protected Menadelook and his immediate family and other communities further north. The flu is the defining historical event of the area during Menadelook’s life, and the photos reflect this in their date references, often simply stating “pre-1918,” or 1920s. Many photos explain the ways that marriages and families reorganized after the decimation wrought by the flu.

Who should read this book

For residents of the region with family who remember this teacher, this book is likely to be an especial treasure. For anyone, teacher, health care provider, or otherwise, who has lived and worked in the region as an outsider, or who is planning to, this book will provide a framework for understanding some of the history of the region from the perspective of those who experienced the rapid cultural changes of the 20th century. Menadelook enjoyed teaching and learning throughout his life, earning respect in the communities he served. He left a historical legacy that his granddaughter had the wisdom and skills to bring together in this fine volume filled with black and white photos and history text. The only thing missing is an index. I noted with surprise that Norbert lists herself as editor of the book rather than author, and while I respect her deference to her grandfather’s extensive journal notes that form the basis of her work, she brought ample writing skills to this book. I enjoyed looking at some of her other contributions to anthropology and the history of Alaska as well, and I will be curious to see what she writes next.

Other reviews of books by or about circumpolar Iñuit . . .

Split Tooth Review: Expressions of the Circumpolar Arctic (book by Tanya Tagaq; review by M. Jacqui Lambert)

Review of Taaqtumi: An Anthology of Arctic Horror Stories

Ice, Fire, Survival in Rural Alaska: Review of Wakolee’s Starting a Fire

Crossing Borders: Review of Floating Coast by Bathsheba Demuth

Some of the above photos were restored by Brian Wallace for Sealaska Heritage Institute.Thank you to the Sealaska Heritage Institute for one-time permission to use the above photos from the book in this post.

The book is available for purchase from our online bookstore here.

I wish I had known this man.