Salmonberries: An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 1

(Note: Transcript of “An Interview with Julia Phillips” has been edited and condensed for clarity).

Listen to “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 1” on Spreaker.

Welcome to our podcast: Salmonberries

Denali Sunrise Publications promotes the integrity and survival of land-based and Indigenous ways of life in the circumpolar North, especially in rural Alaska. We review relevant books, and publish rural Alaskan authors. Welcome to our podcast, Salmonberries, where we bring you stories, interviews, and discussions from across the circumpolar North to surprise, delight, and build community. For more information, please visit our website at denalisunrisepublications.com.

Introduction to Episode One

Our inaugural podcast features an interview with author Julia Phillips, who wrote the debut novel Disappearing Earth, published by Knopf of Penguin Random House in May of 2019. Set in the remote Kamchatka peninsula of Russia, this book is classified alternately as women’s fiction, suspense & thriller, and literary fiction. As I read it, I kept thinking of all the ways it is relevant to Alaska. I was so excited by the author’s approach to storytelling, that I asked her for an interview. I hope you will be as intrigued by the book as I was, and as delighted with the interview.

Julia Phillips tells stories of women’s lives

Here’s the heart of the book: Author Julia Phillips describes women’s lives and relationships with a breadth and depth reminiscent of Leo Tolstoy. And, through the telling of this story, through literary fiction, she brings attention and insight to the complexities of the systems that reinforce discrimination and danger and violence against women, all women, but especially against women marginalized through a long history of colonialism. The author succeeds in keeping this story a work of art while gently educating readers about complex issues, including concerns about murdered and missing Indigenous women. Stories work at the deepest level of our hearts, and this story will nudge people to look at the topic of discrimination with fresh eyes, and a more nuanced understanding of just how a history of colonialism and discrimination continue to reverberate and affect community interactions throughout the world.

Lifting public understanding of the North

The publisher, Knopf, of Penguin Random House, has invested heavily in the book Disappearing Earth, with an initial print run of 125,000 copies. I am grateful that a major publishing company is willing to elevate this story, and the complex and timely discussions it can spark. Even after substantial editing, there’s a lot to think about and digest here, so we’ll release the interview in stages, over several episodes, which gives you time to read Disappearing Earth, if you haven’t already.

Interspersed with release of the podcast episodes, our website will also post reviews of other important books relevant to understanding issues in the rural north, some of which we discuss during the interview.

Let’s begin the first episode!

An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 1

Lisa: I’m Lisa Alexia of Denali Sunrise Publications and it’s July 11th, 2019, and I’m here with Julia Phillips for the author interview about her recently published debut novel Disappearing Earth. So, I have a range of questions and some are geographic and some are literary and hopefully we’ll have fun with this.

Author Julia Phillips

Julia: That sounds really good.

Setting: An American in Kamchatka

Lisa: Let’s start with the setting of your book. I was intrigued both by the location, which is relatively close to Alaska in terms of geography, and also similar in its relative disconnection from the rest of the country. Can you talk about that?

Julia: Yeah. It’s set in Kamchatka, a peninsula also on the Bering Strait; you sort of picture the Aleutian Islands swinging out; they swing in to this, an island chain that’s part of the Kamchatka region. And it is, I think, very similar to Alaska topographically and culturally in some respects, and in other respects of course very different. Kamchatka was a closed Soviet military base for much of the 20th century and it wasn’t permitted for foreigners to visit the entire region, which is quite enormous, the size of California. Although I guess everything is small in relation to Alaska. And so, its modern-day culture is so influenced by that Soviet history, by the post-Soviet moments. It has relatively very very little infrastructure in comparison to Alaska in that, for example, no roads connect Kamchatka to mainland Russia, whereas roads connect major cities in Alaska to part of the mainland continent. So, Kamchatka is effectively an island in many ways. But in the terrain and geography and so much of the culture I think it has so much–It speaks to Alaskan life and landscape in many ways.

Lisa: Geographically we have those roads, but there’s still that sense of, there’s so many communities off the road system and this rural-urban divide, and I think that was a lot of what spoke to me. Thinking about the cover of your book in both the United States and the UK, they’re really compelling in terms of the color and the imagery in the title as well, it captures the color of the sky here in Alaska, and maybe that’s part of what spoke to me. When I first picked it up to look at it, I thought it might touch on environmental issues related to climate change, and I encountered people who saw me reading it when I was in public and they wanted to look at it, and that’s what they started talking about. I was sort of curious to hear you talk a little bit about the selection of the title and that process in relation to the story, because that particular theme actually doesn’t come up in the book.

Cover: Blue-purple light of the north

Julia: I’m so glad you’re talking about the covers, it makes me really happy to think of them as part of the sky. They’re so beautiful and I love that sort of blue-purple mix, I think it’s just gorgeous and very evocative. And the title–makes me laugh. I confess I don’t think I had realized until entering the publication process how sort of climate change-related that is. There are two books that came out in April one called Losing Earth and one called The Uninhabitable Earth, that are both about climate change. So it makes total sense, that’s the association.

Title: Constant threat of loss

Julia: I wanted to call the book Disappearing Earth as a sort of direct reference to a part of the narrative that comes up in the first chapter, which is a story that’s about these two sisters that go missing and one sister tells the other one in the very beginning a story about a tsunami that hit Kamchatka in 1952. She sort of tells an urban legend version of the actual story of this tsunami hitting, that in her telling washes a whole part of the city away, and washes a village away, and then just a few pages later, those characters are sort of swept away by something out of their control and I wanted the title to be a reference to that, to their story and to their experience and also the experience of so many people, so many of the characters in the book more generally, a feeling of building their lives on unsteady ground. They are coming out of a history in which they just lost their nation or their national identity only a few decades earlier. They are very much living in a part of the world that is both prone to geographical or natural disaster, and also a part of the world that is underfunded and overlooked and having a lot of its resources taken from it by the state and is experiencing a sort of constant loss or threat of loss from that. And so, it doesn’t directly allude to climate change. And yet climate change is one of the things that sort of looms over and adds a sense of dread and uncertainty to communities on the coasts and to communities whose lives are so interwoven with the fate of the natural world.

Lisa: Well put.

“They are very much living in a part of the world that is both prone to geographical or natural disaster, and also a part of the world that is underfunded and overlooked and having a lot of its resources taken from it by the state and is experiencing a sort of constant loss or threat of loss from that.”

Structure: Linked short stories form the web of connections

Lisa: In a number of ways your book defies easy categorization. I find myself reflecting most on the use of the loosely connected months of the year as chapters that could stand alone as short stories, and I think I read somewhere that you actually did publish those separately beforehand, as short stories. I was curious about how you chose that particular way to structure your book.

Julia: Yeah, it was a very exciting structure to use. It had some sort of narrative advantages from the start and then it began having some sort of practical advantages as I moved forward with trying to seek publication. The structure of the book was sort of fundamental to it from the start. That was the way I want to approach it, where every chapter moves us forward a month and every chapter introduces a new focus character. The reason I wanted to do that is because the setting was really primary in the creation of the book. I knew the setting before I knew the plot, and as the plot develops, one of the primary motivations for it was wanting to show the story of community, or community dynamic, rather than just sort of a tight focus on one or two or three individuals. So looking at, for example, the story of these missing girls not only as a story of the victim, a perpetrator, and a detective for example, but also looking at the ways that this disappearance sort of echoes and replicates and is reinforced by and is thought to be solved by so many different people. And so I wanted to have a sort of wider focus on the community because of that. I also very much wanted the book to portray a range of violence and women’s lives. And violence, I’m gonna use loosely to mean harm or hurt or or distress. Every focused character is a woman, and every woman in the book experiences sort of a different level of hurt and also hurts others, too. And to me, understanding that web of connections is really fundamental to our understanding both how an enormous violence like the girls’ experience can happen, and also how it can be addressed or resolved or recovered from. So the structure was really really important to me from the start because of that. I also found as I worked on it that, just as you said, it was really advantageous to be able to send chapters out and try to publish some of them while I was working on the book. Rather than sort of working on the whole thing as an enormous secret piece that no one saw, I was working on the whole manuscript and sending chunks out and trying to get those published. That was really sort of motivating and practically helpful. And it’s something I enjoyed a lot doing, and had more success with it in the beginning of working on the book when the pieces were less tightly knit together, and as I revised, had less and less success with publishing pieces separately.

“Russia, Russia, Russia!”

Lisa: You received a fellowship to go to Kamchatka after having spent a year in Moscow and your love for Russian culture and in particular Kamchatka leaps off the pages of this book and your social media posts. Talk about your initial motivation to learn Russian and to travel there.

Julia: Before I went to Kamchatka, I had spent only four months in Russia in Moscow and I went to Moscow for a semester in college because I was studying at the time. I had sort of fallen in love with Russia as a teenager in a very funny way which is that I had a crush on a Russian-American camp counselor when I was twelve years old. Very very silly. Totally lost touch that person, but it was sort of at this moment, this pre-teen moment, where I was so influenceable, and these sort of cultural ideas or books or pieces of art come into our lives at these moments and shape us so much. And for me the exposure to Russian culture really shaped me a lot. I started reading about it and then learning about the history and then reading the literature and it was just so fascinating to me, and I really just became enamored. So I studied the language in college, I studied in Moscow for that time period and I was kind of swept away in love for Russia.

International friendships

Lisa: Do you have friendships there that you still maintain?

Julia: Yes. Especially friendships from Kamchatka in particular. I spent about a year and a half in Kamchatka in total. And folks there really invested in me and welcomed me and took care of me. I was there alone without any support network and people there really made it their business to create a support network for me. And I’ll always be grateful for that and feel connected to that. And it has created a really robust bond I think and so certainly like, I think I probably talk to someone from Kamchatka every day, whether it’s through social media, or through WhatsApp, or through email. You know there’s sort of this constant connection.

Lisa: Does that take place in Russian, or in English, or?

Julia: A lot of it takes place in English now, it’s because people are so tender with me, and understand that my my Russian has–I haven’t been to Russia since 2015. So my language skills have gotten rustier and rustier. I have high hopes that the next time I go to Kamchatka I’ll shake the rust off and be able to speak again. But it’s tough these days.

On the influence of Leo Tolstoy . . .

Lisa: OK. (pause) Despite other comments you’ve made elsewhere about not trying to imitate Russian writers and that the writers you emulate are distinctly North American (I’ve seen you mention Munro and Erdrich), there is a depth of observation of female relationships that I haven’t really seen ironically, since I read War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy. And your attention to the details of human interactions, particularly of women, was a quality I really appreciated about this book. How much influence did reading Russian literature, Tolstoy or others, influence your writing style or approach to this book?

Julia: Lisa, you’re making me cry! That makes me so happy. I’m an enormous, an enormous fan of both Tolstoy and Chekhov. And I say that, I mean you’re absolutely right, that something I’ve said in interviews, something I’m I’m quick to say, and I think is important to say, is that Russian literature is not the school of writing that I have studied for example, in creative writing classes, or examined the craft of, or tried to emulate on that sort of level. But the depth of relationships in Tolstoy and Chekov, the subtleties of human behavior, as a reader, those things really blow my mind. And I remember very well, I felt that way reading War and Peace and I felt that way reading Anna Karenina; with both of those books feeling, having my mind blown that one person could embody and communicate so many different life experiences. That’s just, is stunning to me, and an extraordinary inspiration. I think other writers do it, but to me Tolstoy, like oh my goodness–I just, I’m just stunned, he’s sort of the hero for me in that respect.

. . . and of Louise Erdrich

Lisa: In an interview with Jennifer Wilson for the Paris Review, you mentioned that Louise Erdrich is an influence and that you are compelled by concerns about gender-based violence as you’ve spoken about, especially when connected to failings of a larger system. And your story revolves around the disappearance of not just two but three girls, one of whom, Lilia, is an Indigenous Even teen who disappears before the story starts. I want to hear more about the influence that Louise Erdrich or other authors have had on you or this work in regard to gender-based violence.

Julia: I remember when this book was on submissions speaking to an editor, and she asked me a really smart question, I thought. She said, and a question I hadn’t really ever thought about before, she said “What kind of writer would you like to be like, or who’s your role model, you know, what sort of career or craft would you like to have?” And I said “Louise Erdrich.” I just think she is a genius on the page. I think she is an icon in the literary community, the way that she lives her artistic values and creates space for other writers I think is extraordinary. And you feel that sort of deep morality but also sharp observation, uncompromising observation, in her stories. She is unbelievable to me. I feel like we’re so lucky to be alive at the time that she is writing and publishing her books. She is just unbelievable. Her work is extraordinary and keenly observed treatment of, certainly of gender, of race and ethnicity, of class, which I think are things that every–I was about to say I think these are things that every writer should do. But I am going to revise that to say I think these are the things that my favorite writers do because they’re the things that preoccupy me all day and so that, when I see that written and explored in work it seems to me like a reflection of life, in just the way I want art to be. It’s really important to me and, and reading her work always teaches me and opens up my mind and my heart and just makes me see so much of the world and of experience daily experience than I did before. And so the thing I actually admire most about her writing is not her subjects, although I think the subjects are essential and right and shouldn’t be anything else and must be what they are, but to me it seems like the subjects of her writing are what everyone should be writing about. I mean she’s just talking about what—she’s just being a standard bearer for all the stories that I want to read. It–she’s such a good storyteller. She has so much, she’s so funny and, but, how funny she is only increases the depth and tragedy and beauty and sadness of her work. She just like, she has it all and no matter how heart-wrenching it is, and no matter how absurd it is, and no matter how anything it is, she just pulls you along in her storytelling because she’s so incredibly skilled. She’s like the best person you’ve ever talked to at a party or something. You read her work and you’d just follow her anywhere. I think she’s extraordinary.

Lisa: Yeah, I read some of her books when I was younger and then I came around to reading The Round House in the last few years and that one that blew me away, and I wonder if it’s both her maturing as a writer and me maturing as a reader. That definitely was a galvanizing moment.

Julia: Oh, my God. The Round House, I just like fell on the floor when I read that book. And it’s funny we just, in one of my book clubs, we just read Plague of Doves. A lot of the book club was just all of us sitting around being like, “How is this so good? It’s so good!” This is the best!

Media’s role in disappearing infrastructure,

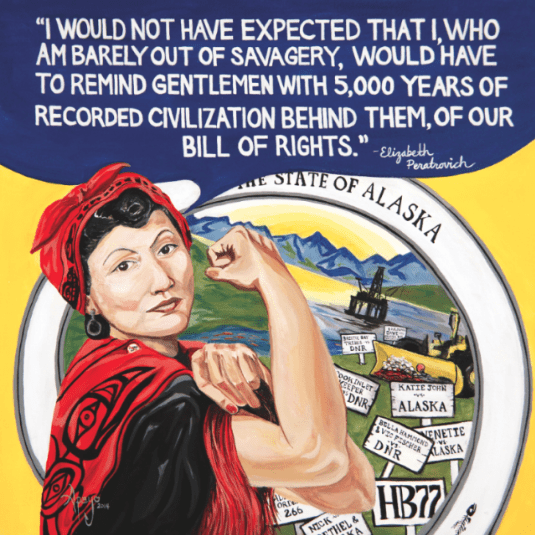

Lisa: I was particularly drawn in your book to the way you tackled the differences between how the media responded to the disappearance of the two younger ethnically Russian girls versus Lilia, an Even Indigenous teen girl’s disappearance several years prior. This quote on page 73, felt to me like the crux of your story’s conflict. Chander, a Koryak man is talking with Ksyusha, an Even woman before dance practice in Petrapavlovsk-Kamchatsky, the only large town on the peninsula. Chander says,

“Something happens in the north and no one pays any attention. Then the same thing goes on down here and it’s news. When we had the fuel crisis in ‘ninety-eight, remember? At home we had a solid year without power. People froze to death in Palana. But the ones in the city talk like it was just three or four months of cold, like the rest of the time didn’t matter because it only happened to us . . . Or the two Russian girls who went missing over the summer. The media report on it constantly. They show us the police officers and the girl’s mother until I know those faces better than I knew my own neighbors growing up. But what about that Even girl who disappeared three years ago. Who covered that? Who even thinks about her anymore?

“The girl from Esso?” Ksyusha asked “Lilia.”

Murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls,

Lisa: So I wondered if you were attempting in Disappearing Earth to take on directly the larger concern about murdered and missing (Indigenous) women in North America? Can you talk about that?

Julia: Yeah. I was attempting to do that without the depth of knowledge that comes from being embedded inside the . . . I think genocide, the crisis of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls in the US and Canada. There is a specificity to that, that my book doesn’t dig into. I would say the level at which I was writing, was thinking about that from that sort of presentation of “perfect victim.” That’s the presentation of often a white or young or blonde or virginal or all of those things together, girl. How she is positioned in media, how she is sensationalized and fixated upon. You know, all people experiencing violence, especially those who are racialized, who are are looked at by media as . . . less than. And I think as a reflection of culturally those who are given less resources and oppressed and endangered. It is something that is specifically, robustly true about Indigenous women and girls in our culture. And it’s a reflection of a phenomenon that is true I think across all people of color in this society. And so I say that to say I didn’t dig into the specificities of Indigenous experience in this book when it comes to that ongoing genocide. I think it refers to it rather than . . . does that makes sense?

Lisa: That. Yeah. I just. Yeah. It’s good to hear you reflect out loud about what I saw as some of the deeper layers of the book.

Julia: Yeah.

Lisa: So you know now it’s interesting to hear you reflect that. Yeah that was a piece of it that there’s some connection to what’s going on in Alaska and Canada because it’s very true.

And the urban-rural divide.

Julia: I think it’s so, profoundly important to this story, and what Chander is talking about is, it’s so reflective of the urban-rural divide of ethnic and cultural oppression on the peninsula, of colonization on the peninsula and dynamics that, you’re 100 percent, you know it better than I know it, the dynamics in place in Alaska and Canada, the lower 48. And I say that at the same time I say, there is so much extraordinary work and research and activism around missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. And that is really really important to dig into. I would love if folks reading this book are encountering that topic in a way that is provocative to them, or opens up to them this idea for the first time for some reason for them to pursue that more robust and specific scholarship and activism, because, ’cause there’s so much there.

Lisa: There is, there absolutely is.

(For more information on the topic of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) in North America, see our resource page, Freedom and Security, (link there to current newspaper coverage of the two-tiered justice system in Alaska as well as Amnesty International report and Canada report on MMIWG) and read The Round House by Louise Erdrich. Related scholarship has also been done by Canadian Ojibway journalist Tanya Talaga, see her books Seven Fallen Feathers and All Our Relations.)

Media divides continue,

Lisa: So, along with that, I was curious to what extent this is an issue the same way in Kamchatka, or elsewhere in Russia the way it is in North America, and if you can reflect on some of those similarities and differences, or how it may have changed over time.

Julia: So, there is very definitely a divide, a sort of media divide, a media focus on cities in Kamchatka, on ethnic Russians, sort of persons of interest or focus–that divide is very strong, I would say, racist, classist, urban-focused media, or culture, which I think is absolutely reflective of, or at least it’s a parallel for, what we experience here. I think that is absolutely true of the United States, 100 percent. Which I think is why I’m looking for it in Russia, and why I perceive it in Russia, because that is the context out of which I’m coming and I’ve lived it, is this American context of racism, classism and city focus. I am not clear, on whether Kamchatka specifically is experiencing an epidemic of murdered and missing Indigenous women in the same way that we are. I don’t know, and I haven’t been able to find any research that has taught me that. It may be there, and it’s a failing of my lack of Russian fluency that I haven’t been able to find it, but I haven’t been able to find it. The way Russian scholarship is developed and shared is among channels that are sometimes hard for me to access. And it’s not something that folks are necessarily comfortable speaking with me about when I’m there as a foreign writer.

Along with missing person posters across the North

Julia: There was a case going on in Petrapavlovsk-Kamchatsky while I was there, and while I was researching and writing this book, that I actually only fully understood after it was finished–both after the book was finished, and after the perpetrator was arrested, which was that there was a serial killer of young women operating in and around Petrapavlovsk, in ways that were extremely sort of resonant of the story that I ended up writing down. And I didn’t realize at the time, that part of the original impetus of this story was seeing some missing person posters around Petrapavlovsk when I was there in 2011. Only later did I understand who this serial killer was, only later did the city understand who this serial killer was, and that he was a serial killer who had been operating at all, and was I able to put two and two together between those posters, and those missing young women, and later, what had turned out to be those crimes. I sent the manuscript to a friend in Kamchatka to read and he was like, “Did you pick this car model because of the serial killer who had a Toyota here?” And I was like “What?!” So he was operating between 2010 and 2014 in Kamchatka, and then arrested in 2014 and died in 2016.

Lisa: Wow.

Julia: Yeah.

End of “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 1”

That concludes the first of several episodes of “An Interview with Julia Phillips.” Please subscribe to our podcast, Salmonberries, to be notified when the next episode is released. Please go to our website at DenaliSunrisePublications.com/blog/ to read our book review of Disappearing Earth, including a list of books we discussed during the course of the interview, and to read a transcript of this podcast episode. Our blog also reviews other books relevant to understanding rural Alaska and the circumpolar north. Thank you for joining us today.

Remainder of interview coming soon

If you enjoyed Part 1, please tune in to the remaining 3 episodes which will be under 30 minutes each. Our extensive interview touched on many specific themes that intersect between Kamchatka and Alaska, providing international insight on the rural/urban divide, changing sources of food and energy, murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (#MMIWG), the experience of gender and culture and ethnicity in the north, and of course, books (see below).

Newsletter notification and link will go out as each recording goes live and the corresponding transcript is posted. (Newsletter signup form is at the bottom of this page). If you’d like to buy the book and read it first, it’s available at our online store (click on the “buy this book” link in the box below), or buy the book at your local bookstore. For more information about justice issues and resources in Alaska, please check out our page, Resources: Freedom and Security. See also our blog post, “Indigenous Women Authors: Review of The Round House by Louise Erdrich” for more on the topic of representation of Indigenous women in literature.

Podcast download links

This episode is available for download on any of the following linked services:

Authors & books, books, books

The following is a list of some of the authors and books mentioned throughout the course of the interview. Links provided to the books available in our bookstore:

Alice Munro

Louise Erdrich (The Round House, Plague of Doves)

Tanya Talaga (Seven Fallen Feathers, All Our Relations) (book reviews coming soon)

Leo Tolstoy (War and Peace, Anna Karenina)

Yuri Rytkheu, a foremost Indigenous Russian author from the Chukchi Peninsula, wrote several books that have been translated into English. A Dream in Polar Fog (translated by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse) and published by Archipelago Books, translation © 2005, originally published in Russian in 1968. Ryktheu also wrote the Chukchi Bible (also from Archipelago Books, © 2011). Coming this fall from Milkweed Editions is a third book by Ryktheu, translated by Chavasse, titled When Whales Leave.

Floating Coast by Bathsheba Demuth, check out the book review written by Julia Phillips for the New York Times. Published by W.W. Norton & Company, © 2019

Other recently released books mentioned during the interview:

Losing Earth by Nathaniel Rich

Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells

Kamchatka Picnic. © Julia Phillips

Denali Sunrise Publications Bookstore

Click on the button below to purchase this book in our store

(or buy it at your local independent bookstore)