Good Seeds: A Menominee Indian Food Memoir by Thomas Pecore Weso

Good Seeds: A Menominee Indian Food Memoir by Thomas Pecore Weso

Wisconsin Historical Society Press, © 2016

Indigenous Anthropology of the Upper Midwest: Wild Rice People

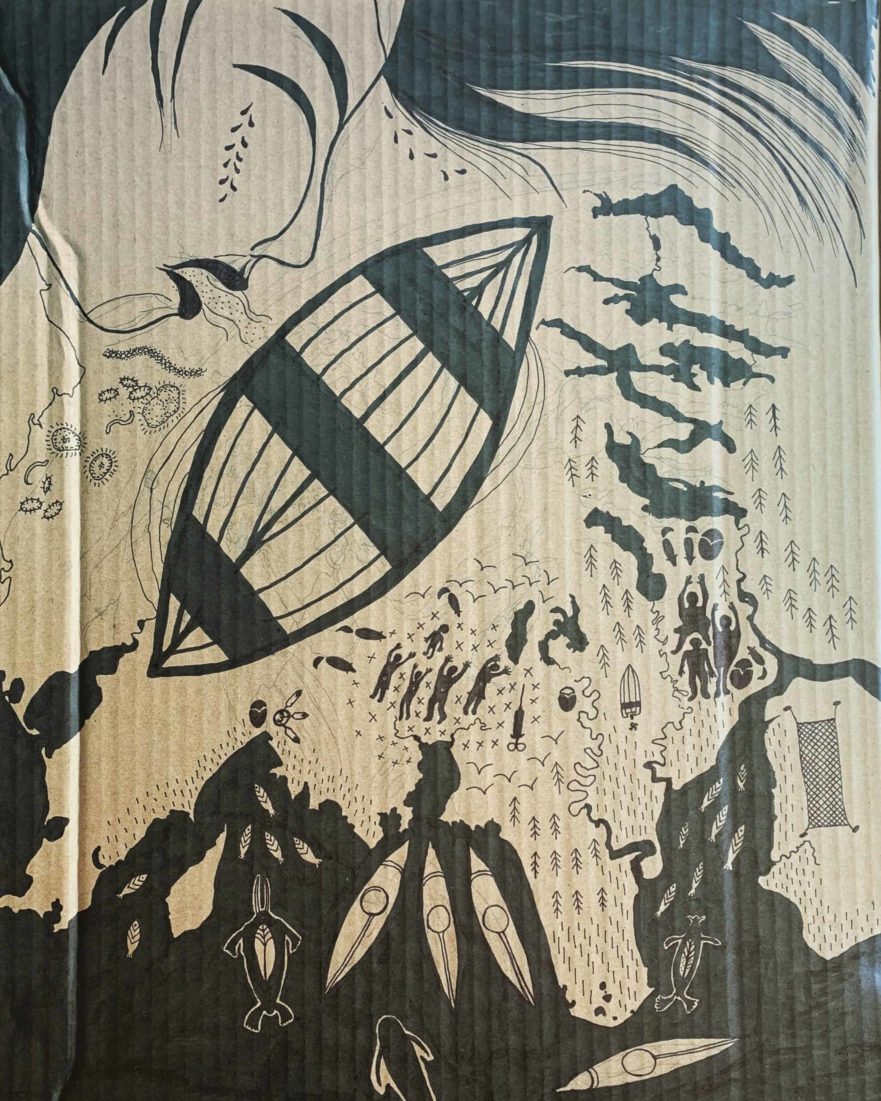

Wild rice is a storied and staple grain throughout the upper midwest. The tribal name ‘Menominee’ is a term of reference from the neighboring Ojibwe, meaning ‘Wild Rice People.” Canoe harvesting and low-technology processing of wild rice continue today by Ojibwe and Menominee, as well as later Scandinavian and other immigrants. I once helped harvest wild rice in Minnesota many years ago with friends; it was a touchstone experience, and wild rice remains a staple in our family’s diet. Thus, the cover image of a canoe nosing through a wild rice bed grabbed my attention.

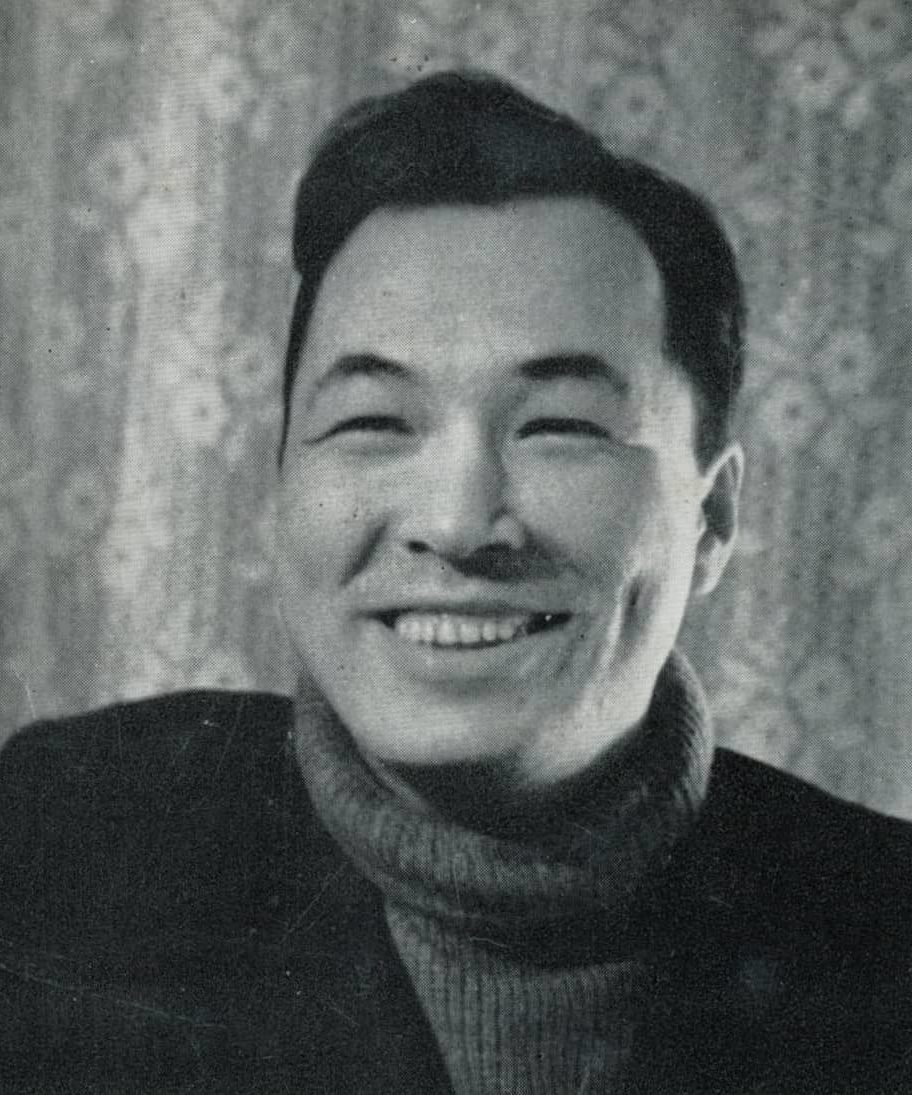

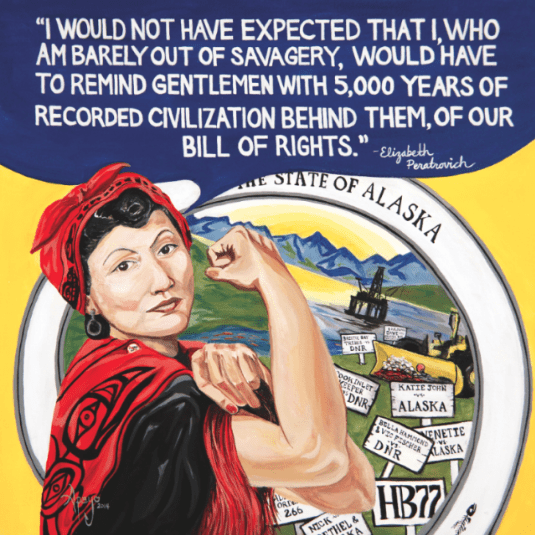

This is an anthropological work about Menominee food traditions, done by Thomas Pecore Weso, a Menominee artist and anthropologist, and a member of the culture he writes about. The author’s view from inside adds a critically important perspective to understanding American food traditions.

Sugar Bush

Weso captures a moment in time and cycles through the seasons with stories and recipes. I enjoyed especially reading about the maple sugar bush traditions. Similar to Alaska fish camp, maple sugar harvesting and processing has remained a constant in the life of the land. This tradition is honored in community with others, both by those who are from the land of maple trees as well as by immigrants to the maple forest.

The Intersection of Multiple Traditions

Many parts of the far north are ‘hungry country,’ meaning that pre-columbian populations were smaller due to more limited indigenous food sources. The soil in the far north is often too new to support the kind of agriculture we think of in the heart of the country, and the growing season shorter; the fish and game generally smaller, leaner, and more sparse in the north away from coastal areas. I was blown away by his description of growing up at the intersection of three traditional food regions: Big game of the western prairies, farming of the east, and fish and wild rice of the northern waterways. He noted, “Menominee people used all these foods, and all combine well with wild rice–meat, fish, and berries.” (p. 49) His generous descriptions of food traditions are accompanied throughout the book by modern recipes using the foods described as well as modern staples of sugar and flour.

Integration of Post-Colonial Technology

There’s plenty of straightforward information here, and some wisdom as well. His comment, “Grandpa always said that one of the few good things that white people brought to us was a frying pan,” has already been absorbed into my own family’s lore.

As his book progresses, he talks about the complexity of his uncle, a WWII veteran. His uncle’s methods for making blackberry wine were not about just making alcohol, but had everything to do with getting the youth outdoors, immersed in traditions from their own culture, and hearing stories from their elders. “That summer we learned chemistry and horticulture. We learned traditional medicine as well as the tribal lore Buddy taught . . . He was trying to establish a new culture. Sometimes that coincided with being a good citizen and sometimes it did not. So there is an element of rebelliousness in that.” (p. 84/85).

An American Story, Told Through Food

Reading works by indigenous Americans means grappling with a history that is devastating and this book is no exception. In understated manner, Weso describes a few places where dams flooded wild rice beds and forever changed the community’s patterns of food harvesting. The Menominee tribe itself was ‘terminated’ in 1958 and through landmark legal action brought by the tribe, they regained federal recognition in 1973. Despite the lack of official recognition during those years, the community continued their harvesting tradition as much as they could. Weso doesn’t delve into the emotional impact of this period of loss but instead quickly goes on to emphasize his community’s resilience. He describes his family’s ongoing interactions with immigrant neighbors at county fairs and in everyday life, painting an image of the new food traditions that evolved as people interacted.

Weso interweaves tales of traditional food in his family, with the changes of colonization, reflecting the heart of American experience in the 21st century. There is a generosity of spirit here, a passing on of knowledge in a modern format. The book is accompanied by both an index and a bibliography. It is available at our online bookstore, or you can buy it directly from the publisher, Wisconsin Historical Society.

For more about indigenous anthopology, see the book review on this website of Menadelook: An Inupiat Teacher’s Photographs of Alaska Village Life, 1907-1932 by Eileen Norbert.

For other links of interest to the circumpolar north beyond Alaska, see this resources page.

To purchase traditional wild rice, here is a list of sources in the upper midwest.

Thomas Pecore Weso

Educator, Author, Artist

Thomas Pecore Weso is an author, artist, and educator from the Menominee reservation in Wisconsin. His website featuring his book provides more information about his writing and art.