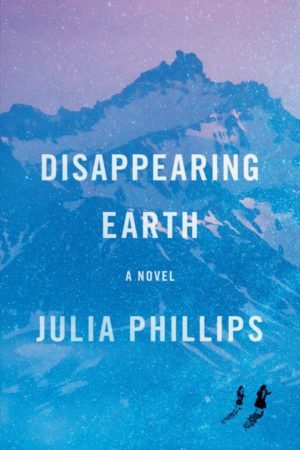

Disappearing Earth by Julia Phillips has relevance for Alaska

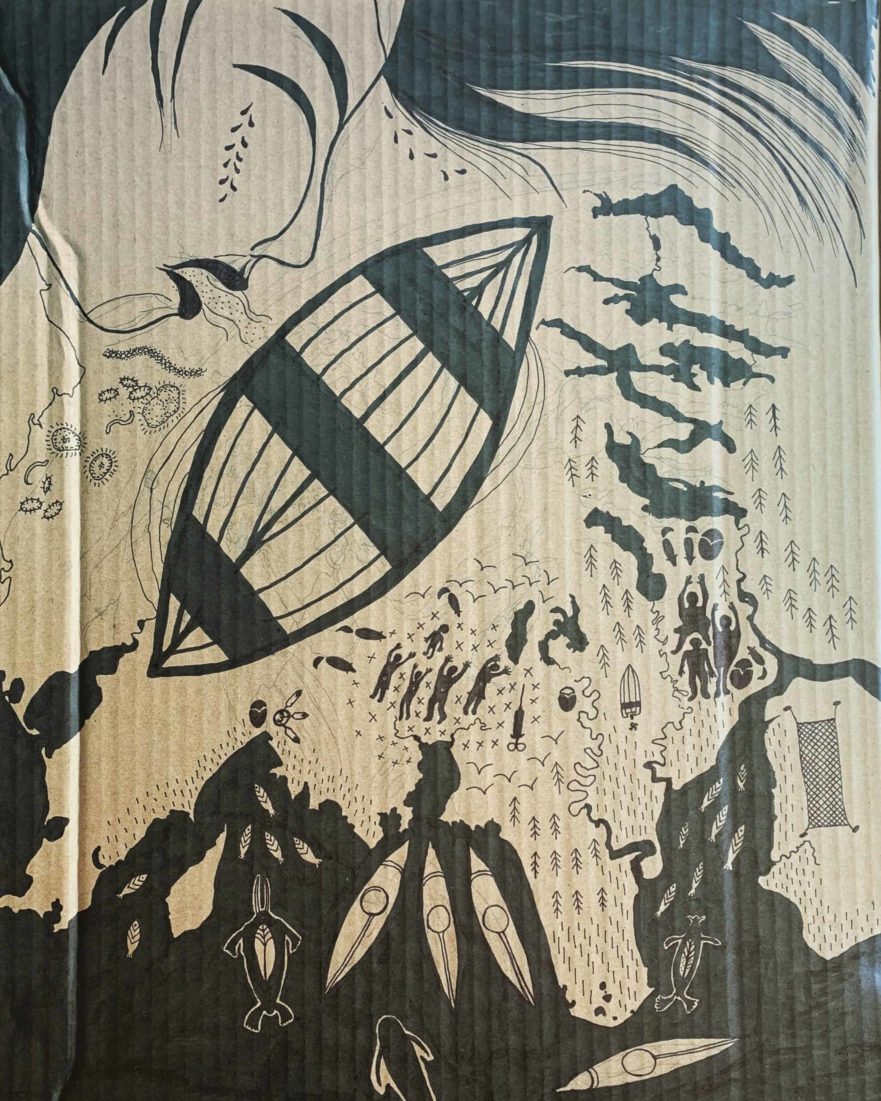

Set in the Kamchatka peninsula of far northeastern Russia, debut novelist Julia Phillips writes in Disappearing Earth about the interior worlds of women, the importance of community, and the impacts of gender-based violence on both, with a depth of human insight reminiscent of Tolstoy. The story opens with the kidnapping of two young Russian girls from the region’s largest city, who we understand are Caucasian. This horrific loss is later juxtaposed with the prior disappearance of an Indigenous Even teen from a remote village family.

Disappearing girls and the complexity of responses

Through this plot twist, Disappearing Earth presents the complex influence of cultural differences, colonialism, and the rural/urban divide on law enforcement and public response to the disappearances, all in the context of post-Soviet Russia. Loosely connected stories through the months of a year reveal the range of emotional impacts these disappearances have on women among the interlinked villages of this peninsula with no roads connected to the outside world.

Geography and history constrain patterns of behavior

In the rural north of Disappearing Earth, conflicting desires and impulses settle into maturity and acceptance of community expectations. Relationships between people of multiple cultures, ages, and beliefs reveal intergenerational struggles between those who experienced the relative wealth of Soviet Kamchatka and the younger generation who have grown up with Internet and social media. And the disappearance of the girls impacts every woman in this story, weaving into their larger internal narrative,

” . . . Kamchatka was no longer a place to raise a family. Just look at the hole in her cousin’s life where a daughter belonged. The communities Revmira grew up in had splintered, making them easy places to be forgotten, easy places to disappear. Revmira’s parents had raised her in a strong home, an idyllic village, a principled people, a living Even culture, a socialist nation of great achievement. That nation collapsed. Nothing was left in the place it had occupied.” (p. 140)

A visitor’s perspective to the landscape of Kamchatka

Phillips spent time in Moscow in college, and later spent a year in Kamchatka on a Fulbright. Book publicity has emphasized both its landscape description and the human interactions. Her perspective as an outside observer being out on the land will feel especially familiar to those who moved to the rural North later in their lives:

“Esso in the summertime was beautiful–cottages were repainted in primary colors, gardens grew dense with vegetables, the rivers ran high, and the mountains that surrounded the village turned dark with foliage. Ksyusha did not get to appreciate the sight until she was seventeen years old. Instead, the demands of herding ruled her summers: kilometers on horseback, legs aching, back sore; mosquitoes crawling under her clothes and staining her skin with her own blood; hurried baths taken in freezing river water . . .”

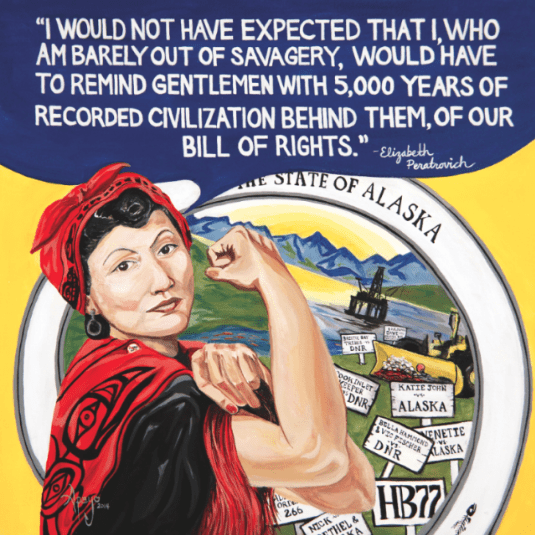

Representation matters: advocacy and community building in Disappearing Earth

Indigenous characterizations are handled cautiously, with awareness that she lacks a deep familiarity with the rhythms of life on the land. Still, there is nuance here; she makes the reader think about Russia’s diverse cultures and complicated history. It’s refreshing to see this attention to justice through a range of community interactions among people of various cultural backgrounds, in a novel written about people living in the north. It’s clear that she was deeply affected by the time spent with people in rural Kamchatka, both ethnically white as well as Indigenous Russians, and whatever American motivations and perceptions she brings to the story, she has done her best to represent fairly the cultures and conflicts of a place with problems perhaps not so very different from our own in America, and in particular, Alaska:

“Something happens in the north,” he said, “and no one pays any attention. Then the same thing goes on down here and it’s news. When we had the fuel crisis in ‘ninety-eight–remember? At home we had a solid year without power. People froze to death in Palana. But the ones in the city talk like it was just three or four months of cold, like the rest of the time didn’t matter because it only happened to us.” (p. 73)

In Disappearing Earth, a major publisher brings attention to these complex issues

Knopf backed Phillips with the expertise of their Editorial Director Robin Desser, who also edited Wild by Cheryl Strayed. Penguin Random House has invested heavily in Disappearing Earth with a first-run printing of 125,000 copies. With increasing publicity in Alaska and Canada about longstanding concerns of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the north, this debut novel, presented with enthusiasm from a major publishing house, has potential to spark broad reflection and public discussion in North America about the misperceptions and walls between communities and structures of governance that must dissolve in order to bring these women home.

Writing and cultural exchange across the circumpolar North

On an Instagram post just prior to this book’s release in May of 2019, Phillips expressed her gratitude and sense of overwhelm concerning time she spent with a reindeer herding family in central Kamchatka the summer of 2015, revealing how much she is still struggling to understand what she saw and felt during that season. This description resonated so much with my experience moving to rural Alaska, that I reached out directly to the author to request an interview, which she graciously granted. This post originally posted a transcript of the first few minutes of that conversation, which has now been copied over to the full post of the transcript for “An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 1“.

The interview lasted several hours and will be condensed into 4 episodes with transcriptions posted on the blog. Julia Phillips speaks eloquently on multiple topics related to Indigenous representation and justice as well as many other topics related to gender-based violence, colonialism, and efforts to preserve traditional ways of life in the north. Interspersed with these episode postings will be book reviews of Indigenous northern writers writing on these topics and other significant literature of the north.

If you’d like to be notified as the posts are released, please use the signup form on the bottom of the page if you aren’t already receiving our newsletter. If you’d like to listen to the interview episodes, please click on any of the links below to subscribe to our new podcast, Salmonberries, on your favorite podcast app.

Podcast download links

An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 1: Click here for immediate download of MP3 file, it will start playing immediately upon download.

The first episode is available at the following places, more direct links to the first episode of our podcast, “Salmonberries” (An Interview with Julia Phillips, Part 1) will be added below as they become available (access pending at multiple other podcast venues):

iHeartRadio (pending)

Deezer (pending)

Denali Sunrise Publications Bookstore

Click on the button below to purchase this book in our store

(or buy it at your local independent bookstore)

You are doing amazing and much needed work here Lisa! Love the interview! Website is evolving and love it! Keep up the great work and know that it is very much valued!!

Thank you, Karen!